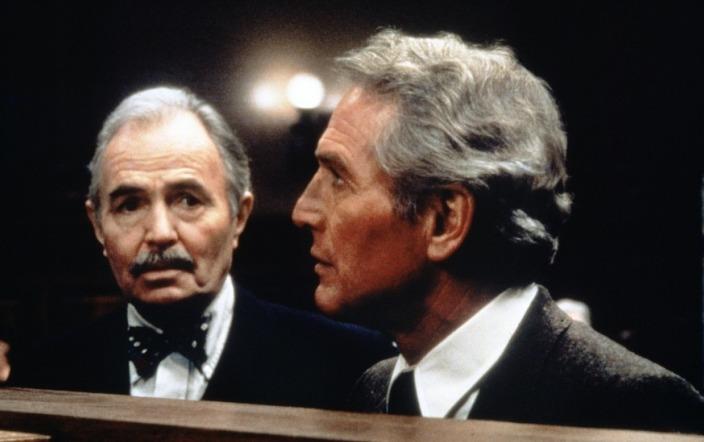

5. Philip Seymour Hoffman and Ethan Hawke as Andy and Hank Hanson in Before the Devil Knows You’re Dead

It’s hard not to watch Lumet’s swan song without immense sadness now that both its creator and lead actor have passed, but that doesn’t stop my admiration for this tour de force. After much deliberation, in discerning who deserved the most recognition on this list, it became impossible to separate Ethan Hawke and Philip Seymour Hoffman’s spectacular chemistry.

Although these two look nothing alike, we know they are brothers. They embody the same caricatures but with different impacts, they flow with a desperate rhythm as if they had struggled together since childhood, and they embody the destruction of character and morality with such finesse that any other performer would never be able to reach the heights of talent found within this film.

The analogy of the snake and Adam is apt when describing their act; Hoffman is Andy, the desperate businessman who’s deep in debt and looking to escape, and he brings a ploy to Hank, his broke brother who’s looking to support his daughter. The ‘apple’ that he lures him in with is none other than their parents’ jewelry store; it’s easy to rob and generates a lot of cash, but it all goes wrong and when it does, things go from bad to worse.

As things fall apart, we see another spectacular performance from Albert Finney, but all the spotlight is taken by these Hoffman and Hawke, as they leap through hurdle after hurdle trying desperately to escape something they never will.

It’s an incredibly delivered swan song that rivals even his greatest work, forever reminding audiences that Lumet never lost his ability to make movies, and we can only imagine what it would be like if Lumet ever had the chance to pair up with these two again.

4. Paul Newman as Frank Galvin in The Verdict

When most directors were beginning to tumble in their careers in the 80s, Lumet stood out, continuing to maintain his reputation as one of the most consistently brilliant filmmakers with “Prince of the City” and “The Verdict”. Paul Newman delivers a tragically brilliant performance in this twisted redemption story as an alcoholic, washed-up lawyer with one last “make it or break it” case.

While its premise is formulaic, what Lumet does differently is use the case simply as a propelling board for an intense character study of both James Mason’s Ed Concannon and Newman’s Frank Galvin, and although many accolades went to Mason, it was Newman who captivated cinephiles.

While most of Lumet’s characters unfurl from maintained to manic, we observe the contrary as Galvin builds himself up with such power and grounded realism that we often forget he’s a fictional character.

“The Verdict” is perhaps one of the most influential courtroom dramas in history, perhaps second only to Lumet’s own “12 Angry Men” and Robert Mulligan’s “To Kill a Mockingbird”. With intelligent drama, smooth dialogue, and riveting characters, this will be just one of many landmark films Lumet made to impact an entire decade.

3. Henry Fonda as Juror 8 in 12 Angry Men

Although a special mention goes to Lee J. Cobb, it is Henry Fonda’s starring role in Lumet’s debut film that stands as the greatest performance in this tour de force of a film.

Juror 8 is the crucial moral compass of the film, the man who asks “but what if we’re wrong?” “Do we want to send this boy to die?” These are the fundamental overriding questions permeating this intense, real time drama, and through Fonda’s iconic performance, it is a riveting watch.

The film does not tell us whether he is guilty. It doesn’t tell us what is wrong and what is right, instead choosing to explore the inner workings of each juror, the ‘why’ to their declarations of ‘guilty’ and ‘not-guilty’.

These inner workings are not thrown in our faces but instead a more subtle picture is painted; small observations here and there, an occupation, or simply an attitude that defines them.

As the moral beacon, Fonda’s role is not to make us understand why he says “no, this man does not deserve to die”, but instead it is his job to convince you, me, and the other jurors of that very thing. A combination of perfect dialogue, taut direction, and Fonda’s masterful performance do that very thing and more.

2. Peter Finch as Howard Beale in The Network

The first posthumous Oscar ever given still stands as one of the most well deserved. It is not often a director makes five films that are consecutively nominated for Best Picture at the Oscars (“Serpico”, “Murder on the Orient Express”, “Dog Day Afternoon”, “Network” and “Equus”), with each one handled with finesse, but Lumet appears to have made it seem easy. Peter Finch delivers his tragically brilliant final performance with such inspired madness that it lives on to be quoted 40 years later.

Finch plays Howard Beale, a news anchor manipulated by his network following mad ravings, and we watch him twist in the wind and desperately struggling to anchor himself, while Faye Dunaway’s Diana Christensen uses him expertly.

It’s a tragically hilarious performance, adding just the right notes of humor to the perfect torment needed to make us simultaneously pity him yet laugh at his actions, and in doing so, Lumet and Finch push the power of their film like the masters they are.

Few films today have the power to so expertly suggest that we question what we watch, what we read, and what we understand, and although it is common knowledge now that we are influenced by propaganda-like media, it was here that we were first conveyed (by a film, ironically) that very message.

“Network” was a revolutionary film and a tour de force, and perhaps what makes it so incredible was, much like Paul Thomas Anderson’s “There Will Be Blood”, even if you removed Finch it would still be a great film. Coupled with his magnificent performance, this film will stand the test of time, perhaps perpetually, and his performance as one of the greatest in film.

1. Al Pacino as Sonny Wortzik in Dog Day Afternoon

Perhaps one of the greatest films of one of the greatest decades in cinematic history, “Dog Day Afternoon” challenges all aspects of society: the morality of the criminal, the power of media, sexuality, the hypocrisy of audiences, and most of all, the establishment. Lumet’s magnum opus, although receiving praise at its release, stands now much like “Citizen Kane” as a film acknowledged by critics but not fully realized for many years to come.

Al Pacino’s Sonny is a gay man, married with anger management issues, but also in a relationship with the depressed and unstable Leon. He and Sal have robbed a bank – his motivation? To get the money to afford Leon’s sex change.

The film slowly uncovers the plotline with a mix of the gripping claustrophobic feelings Lumet drew from “12 Angry Men”, mixing them with the subtle notes of humor he would later unfold in “Network” to create a film that draws all the right parts from all his bodies of work, creating a mediated, powerful, funny, and ferocious challenge to the personalities and perspectives of our society.

At its heart is Pacino’s Sonny, an embodiment of the heroic idealism we relish from our protagonists, yet caught up in a criminal act in challenge against the government. He becomes a hero for his bellowing “Attica!” as loud as he can, and the protestors of the 70s revel in his defiance, yet when uncovering his homosexual agenda, they begin to mock him.

He ceases to be a hero because… he is gay? These attitudes that Lumet and Pacino explore critique us as an audience yet we don’t even realize it, and now, years later, we come to understand that these attitudes are incredibly influential in the governing of our society.

Sonny points out the brutality of our government, the prejudices of the people, and the blurred morality of our society through action and a lot of words declared like battle cries.

This film is another tour de force, yet it is Pacino’s humane, boisterous, frustrated and desperate Sonny, whose 24 hours of fame invigorate, demoralize and destroy him systematically, which pulls it together so brilliantly.

Again, this isn’t a film without merit from other sources; we’ve already discussed Cazale’s performance, and as Leon, Chris Sarandon pounds the first nails into the destruction of gay stereotypes. However, as Sonny, Pacino makes this a film powerful and so perpetually relevant that neither its message nor its captivating entertainment will ever fade.