“Forget it, Jake. It’s Chinatown.”

– Lawrence Walsh (played by Joe Manetell)

Darkness on the edge of town

A neo-noir masterpiece, Chinatown proves that director Roman Polanski, screenwriter Robert Towne, and producer Robert Evans can make a monumental film wherein they beat a genre until it’s a bloody, swollen, purple-bruised, and marred mess, then dump it in a reservoir of Greek tragedy and lay in universal acclaim.

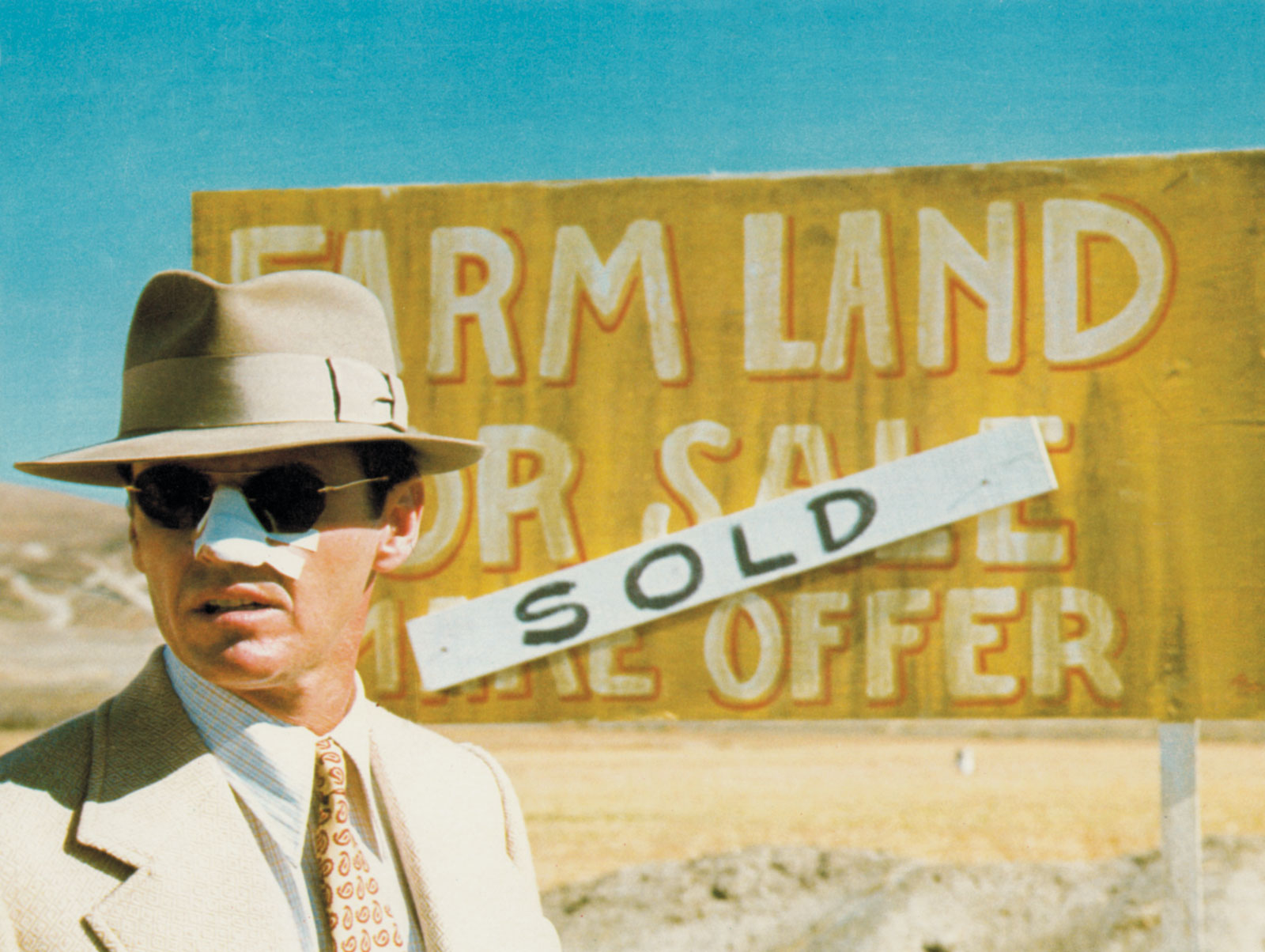

J.J. “Jake” Gittes (Jack Nicholson) is a hangdog private eye, hardboiled, ill-fated and blithely arrogant, his hunches are almost always wrong. Jake exudes a vitriolic machismo, claiming here and there in the odd moment of clarity he experiences that he’s “just a snoop” until he meets depravity personified in one Noah Cross (John Huston). “You see, Mr. Gittes,” he spits, famously expounding, “most people never have to face the fact that, at the right time, and the right place, they’re capable of anything.”

True, Towne’s script acts as something of compendium of film noir tropes and yet it defies them, and, with Polanski’s faultless direction results in a revisionist homage, a 1940s private-eye picture that manages to be both cynical and sentiment in one fell swoop.

“Polanski, whose movies don’t leave you anything to hang on to, turns [Chinatown] into an extension of his worldview: he makes the LA atmosphere gothic and creepy from the word go. The film holds you, in a suffocating way. Polanski never lets the story tell itself. It’s all over-deliberate, mauve, nightmarish; everyone is yellow-lacquered, and evil runs rampant.”

– Pauline Kael

How do you like them apples?

The colossal performances and the forcibly composite puzzle Chinatown presents were overshadowed in 1974, at least when it came to the Academy Awards in a year largely dominated by Coppola’s The Godfather: Part II.

The only Oscar that Chinatown received, from 11 nominations, was for Towne, who wrote the script specifically for his good friend Jack Nicholson. The hard as nails mystery Towne conferred is in the Raymond Chandler and Dashiell Hammett design; it unfolds in Los Angeles, contains a rogue’s gallery of ne’er do-wells, dangerous dames, and a Byzantine conspiracy.

Nicholson’s LA-based private eye is certainly in propinquity to the gumshoes that settle in the Chandler/Hammett subfamily but with decisive twists: Jake is flip and lacks respect when it comes to the police and authority figures. This cheeky iconoclasm is certainly a modern wrinkle owing to the Vietnam war as well as the Watergate scandal.

For these reasons as well as playful messing with pulp-noir convention, Jake is all ‘round more humorous, rakish, well-heeled, and darkly disaffected than Philip Marlowe or Sam Spade. A former cop himself, with a haunted and troubling past stemming back to a time when his beat was LA’s eminent Chinatown.

Jake is hired by a feisty dame (Diane Ladd), identifying herself as “Mrs. Mulwray” (though we later find out her name is Ida Sessions), to investigate her philandering husband’s activities. Mr. Mulwray (Darrell Zwerling), Hollis to his friends, is a well known socialite and prominent chief engineer for the Los Angeles Department of Water and Power, and Jake at first believes it’s all just another tawdry routine infidelity case.

He gets the intimate intelligence on Hollis but also learns tout de suite that his investigation is anything but routine when the real and outraged Evelyn Mulwray (Faye Dunaway) appears and that he was hired by a phoney and he’s been played the fool.

Jake doesn’t take kindly at all to being made a sucker and so investigates further as scare tactics intensify and a trail of dead bodies accumulate. This soon takes Jake down a difficult network of corruption, exploitation, greed, murder, and humiliating and horrible family secrets as Noah Cross –– Evelyn’s father and no-nonsense industrialist tycoon –– becomes a chief suspect.

“Forget Hitchcock. We’ve got Polanski!”

– Tom Burke, Rolling Stone

Another day in paradise

Intrinsic to Chinatown’s sublimity, and perhaps the single greatest reason it attained its near-instant prestige as chef d’oeuvre is the dexterity with which it conjures the Golden Age of Hollywood.

Set in 1937 amidst the orange groves, alleyways and estates of the City of Angels, the film never once loses itself in the sentimentality of the era, nor is it a rheumatic pastiche. And it was Polanski’s conquering genius that made it transcend the calculating and complex narrative into a truly tremendous and deeply troubling noir nightmare.

Using his own personal knowledge of heartbreak and diablerie –– he survived the Holocaust and lost his pregnant wife, Sharon Tate, to the murderous Manson family –– Polanski famously acclimatized Towne’s staggering script, most exigently altering the ending into one of the most unforgettably bleak contretemps possible.

It was also Polanski who perceptively and charitably descried the acquiring of eccentrics, underdogs, and erstwhile degenerates –– including his own brilliant bit part as the “man with the knife” stoolie who snips Jake’s nose.

“Chinatown, one of the best films of one of the best decades in American movie history, is a grinning skull of a movie lewdly murmuring those incantatory, seesawing fragments, ‘My sister, my daughter, my sister, my daughter,’ into our ears. A 1974 film noir set in Depression-era Los Angeles, it’s a fiendishly clever merging of Raymond Chandler, Franz Kafka, and Sophocles.”

– James Verniere

The way you look tonight

Considerable praise also belongs to cinematographer John A. Alonzo (DP for 1971’s actioner Vanishing Point and much later Brian De Palma’s Scarface, amongst other accomplished works), who miraculously achieved the brunt of a black-and-white noir with intense and flashy color photography.

Under his expert lensing we see Los Angeles not as a soot-flecked interurban but as an often inviting, paradoxically sunny, and seemingly limitless boomtown. No wonder such a paradise seemed so ripe and ready for plunder and profiteering.

Similarly, the trembling, almost palsied quality of Faye Dunaway’s elegantly unflappable Evelyn was smartly and cruelly laid bare. Her nevus, what she describes as “a flaw in the iris… a sort of birthmark,” serves as Chinatown’s fractured middle; a heart of darkness. Much more than the femme fatale we first suspect her to be, and the terrible secret she keeps is certainly one of the most shocking reveals in all of cinema.

“It seems like half the city is trying to cover it all up, which is fine by me. But, Mrs. Mulwray, I goddamn near lost my nose. And I like it. I like breathing through it. And I still think you’re hiding something.”

– J.J. “Jake” Gittes (played by Jack Nicholson)

A spectacle of corruption

For all of Chinatown’s dark dreams, languid moves, and seductive dissipations, it is still entirely Nicholson’s show. Jake’s cynical mentions and reflections, his resigned charm, even his bandaged nose and frequent misreading of what’s unraveling before him, make him foolishly fascinating.

Having cut a name for himself via countless Roger Corman biker genre films and more legit and iconic roles in Easy Rider (1969) and in buddy Bob Rafelson’s dramatic conquests Five Easy Pieces (1970) and the sorely underrated The King of Marvin Gardens (1972), Chinatown netted Nicholson his third coveted Oscar nomination.

As with nearly all noirs, Chinatown adjourns with a parade of prophecy and revelation. Explanations are offered up, relationships are elucidated and, for some, redefined. Justice is meted out, though not for everyone, and a shocking capsheaf, anything but rosy, ends the tale. Chinatown dissolves into grief and shock, underscoring what Noah had earlier obliged; that at the right time and at the right place, people are capable of anything.

“Course I’m respectable. I’m old. Politicians, ugly buildings, and whores all get respectable if they last long enough.”

– Noah Cross (played by John Huston)

Author Bio: Shane Scott-Travis is a film critic, screenwriter, comic book author/illustrator and cineaste. Currently residing in Vancouver, Canada, Shane can often be found at the cinema, the dog park, or off in a corner someplace, paraphrasing Groucho Marx. Follow Shane on Twitter @ShaneScottravis.