With some 60+ feature films, shorts, documentaries and various other directed works under his belt, the cinema of Werner Herzog covers a vast landscape of worlds and peoples. He is one of the few directors whose name has given birth to its own adjective – one might describe a film as Herzogian just as one might describe a film as Hitchcockian, Bergmanesque, or Felliniesque – and it is this individuality that allows his work to retain a singular freshness many decades on.

As with many of his peers of the New German Cinema that exploded in the late ’60s and early ’70s, he grew up in a ruined and divided Germany, still rebuilding from the Second World War. Those of his generation, when they came of age in the ’60s, led a wave of student protests and revolts which came to a head in 1968, as it did across much of Europe, most famously in Paris.

Often referred to as the ’68ers this generation was frustrated at a West Germany which had struggled to come to terms with its past, where many civil service posts were filled in by former Nazi party members and conversations about the crimes committed in the name of Germany during the war kept to a minimum.

Overwhelmingly left-wing but also wary of the more autocratic, authoritarian nature of communism on the other side of the Berlin Wall, these protesters were influenced by more fluid and modernist theories of Marxism such as those propounded by the famous ‘Frankfurt School’. Indeed, many of the Frankfurt School’s most famous names, such as Theodor Adorno and Herbert Marcuse, played a significant part in inspiring their students to protest, although many of them would find themselves frustrated at the increasingly violent nature of the protests.

The protests gradually subsided but the political turbulence did not, and it was within this that West Germany’s new generation of filmmakers found their breakthrough. Directors as varied as Margarethe von Trotta, Volker Schlöndorff, Wim Wenders, and Rainer Werner Fassbinder all made deeply personal, complex films that were nevertheless uniquely German. Their films criticised, discussed, and analysed many of the issues that faced contemporary Germany.

Herzog’s cinema at once both stands alongside his contemporaries and apart. Though he too criticised and discussed some of the issues of German society at the time, his films are of a somewhat different nature. They feel less rooted in the ‘reality’ of life, and are keen to engage with more ambitious, grander ideas. Humankind, its history, its very nature are not subjects that Herzog feels shy about tackling for want of knowledge.

From his first short film, Herakles (1962), filmed with a camera stolen (or, as he says himself “appropriated”) from the Munich Film School, to his most recent releases, many of which attract notable stars – his latest, Queen of the Desert, will go on general release this year and stars Nicole Kidman, James Franco, and Robert Pattinson – all have a unifying style and feel that denotes them as ‘Herzogian’.

Themes occur and reoccur throughout most of Herzog’s work, shifting ever so slightly from film to film, symbols of the auteur’s interests and obsessions. In particular, the decade-long hot streak from Aguirre: The Wrath of God (1972) to Fitzcarraldo (1982) was where Herzog really solidified the themes that would so concern him for so many decades. What are some of these themes?

1. Man vs. nature

By far the most palpable recurring theme in Werner Herzog’s work is a sense of man, or at least ‘civilised’ man being at odds with nature. Incapable of understanding its forces, strengths, and never-ending power, the protagonists of Herzog’s films stand aghast at nature, one small speck against its overwhelming wrath. The titular characters in Aguirre: The Wrath of God and Fitzcarraldo (played by Klaus Kinski on both occasions) struggle to contend with the stress of being in the jungle in ways that sends both of them insane.

In Les Blank’s documentary about the making of Fitzcarraldo, Burden of Dreams (1982), Herzog said “I would see [in the jungle] fornication and asphyxiation and choking and fighting for survival and growing and just rotting away. Of course, there’s a lot of misery. But it is the same misery that is all around us. The trees here are in misery, and the birds are in misery. I don’t think they sing. They just screech in pain.”

Such an attitude seems typical of Herzog, a man who always seems to cheerfully see the worst in things, but this attitude also plays through his films. Aguirre seems to be driven mad by the unknowable murder going on inside the Amazon, the fearful growths existing just beyond the banks of the river whilst his men fearfully stay on their slowly-disintegrating raft. The entirety of the film is one long journey into one individual’s increasing insanity, and the environment only drives that insanity further.

One of Herzog’s other collaborations with cinema’s nastiest psychopath Klaus Kinski (and for all his awful faults as a human being, one of its most incredible actors), Nosferatu: Phantom of the Night (1979) also plays on this theme. In the remake of F.W Murnau’s totemic 1922 film, Count Dracula (Kinski) is seen as some sort of semi-natural ancient force, rooted in the craggy Carpathian mountains and wild woods of Romania; his arrival in the supposedly more modern and civilised world of 19th century Germany is trumpeted by thousands of rats following in his wake, plague and havoc being wreaked on the sleepy town.

However, it is in his documentaries that Herzog has gone most deeply into this theme. Grizzly Man (2005) is about Timothy Treadwell, an American environmentalist who went on yearly trips to Alaska in the summer to live amongst grizzly bears.

He filmed many of his trips, getting mere metres away from some of nature’s most deadly predators and seemed to believe he was a friend to the bears. His demise was sadly most unsurprising in its grim nature, but here too we see Herzog attracted to a man seemingly unable to comprehend nature. Treadwell genuinely believed he was able to communicate with animals. Instead he found only hunger and death: “a half-bored interest in food” Herzog says of one of the bears Treadwell filmed.

Yet his view of such a world is not purely negative. Again in Burden of Dreams, he states that “he loves the jungle, against my better judgement”. In Cave of Forgotten Dreams (2011), his first and to date only 3D films, he goes deep into the Chauvet caves in Southern France to investigate the cave paintings found therein.

Staring in silent beauty at these ancient works of art, the oldest and best-preserved cave paintings on earth, he muses about the nature of humanity; the complex way in which we perceived the world even back then, and the way in which ancient peoples too had their struggles with nature. They survived, sometimes against all the odds, and without them we wouldn’t be alive today. Man is nature, even if he doesn’t always realise it.

2. The divide between facts and the truth

Facts are irrelevant. The truth is what matters. This is Herzog’s decree, and it runs through almost every single of his films.

In Little Dieter Needs to Fly (1997), we meet Dieter Dengler, a former US air force pilot who was shot down during Vietnam and held in a Viet Cong prisoner of war camp, from which he later escaped and marched through the jungle to survival. Herzog films Dengler in his comfortable home, constantly opening and checking doors and windows to make sure they are unlocked, out of fear of being caged once again.

Except the real Dengler didn’t do that. This was a detail which Herzog invented, in collaboration with his subject, as a way of reflecting the experience that Dengler went through. The claustrophobia, the fear of being trapped and the struggle to free oneself from that trap were what drove Dengler onwards. To portray that fear effectively onscreen, Herzog took to fiction. That it is factually inaccurate doesn’t matter. It is the understanding we receive that is valuable. Throughout the film, Dengler’s narration is poetic and fluid. Some of the images he uses were in fact real experiences; others extrapolations by Herzog.

Ironically, it is Rescue Dawn (2006), a fictionalised film about the same story starring Christian Bale that arguably reproduces more of the ‘facts’. The fictional film becomes more ‘real’ than the documentary, the documentary less factual than the film. Both in Herzog’s view are incomplete forms, incapable of capturing all of reality as it is.

Instead, they are only capable of capturing segments of it that we then contextualise into our own experiences. These experiences form what Herzog often calls the ‘ecstatic truth’. Verité documentary, the fly-on-the-wall style intended as a way of capturing reality simply by way of pointing a camera at something hoping the truth falls out, is for Herzog, “a merely superficial truth, the truth of accountants”.

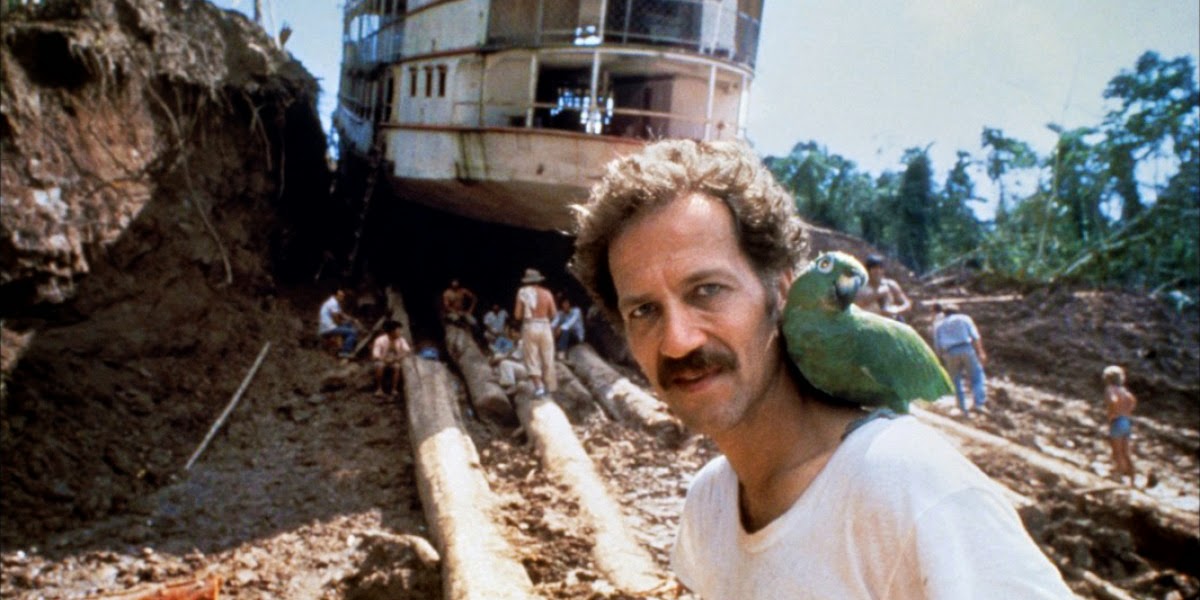

In Fitzcarraldo Herzog drew on the life of Carlos Fitzcarrald, a Peruvian rubber baron who figured out a way of extracting rubber from a notoriously unnavigable part of the Amazon, which required the transportation of a large boat into the central Amazon. Notoriously, Herzog insisted on pulling a huge 320-ton steamship over a mountain onto the river on the other side. The real Fitzcarrald had a mere 30-ton boat disassembled and then re-assembled on the other side of the river.

Leaving aside the sheer insanity and pointlessness of the task, Herzog’s insistence on such a method is his own way of proving to himself and the audience that reality is only what we are allowed to see. Because he insisted such an event be done this way, so the truth (in this case, the sheer pointlessness and eventual worthlessness of ruthlessly exploiting the jungle for capitalist and colonialist gains), becomes apparent.

3. Obsessive, Nietzschean protagonists

That his protagonists are frequently obsessive and insane people is perhaps just a reflection of their creator’s own psyche. Aguirre, Fitzcarraldo, Timothy Treadwell, as well as Terence McDonough (Nicolas Cage) in The Bad Lieutenant: Port of Call New Orleans (2009), to name just a few in his filmography, are all men who seem to believe that they are not bound by traditional morals, that they supersede and transcend such morals.

Aguirre and Fitzcarraldo both embark on colonialist escapades in search for greatness and glory, both turn out to be failed übermensch. They attempt to create something they see as beyond themselves, but secretly they only believe in personal glory, hence they fail.

The same is true of Nicolas Cage in Herzog’s remake of Bad Lieutenant (originally a 1992 film directed by Abel Ferrara and starring Harvey Keitel). Here is another obsessive, masochistic figure, who seems to freely disregard traditional notions and what is good and evil and freely goes about murdering, using narcotics, and abusing others around him. Revelling in his lack of morals, Cage’s unhinged cop somehow manages to earn himself a promotion and a commendation from his superiors, reflecting Herzog’s cynical beliefs in the nature of man.

These men break under the weight of their own rage and fury. Their reaching for some supposed transcendental values that will replace the old Judeo-Christian ones simply appear to turn them into evil men.

4. Tactile, mobile cinematography

Herzog’s desire for experience and truth also leads into his cinematography. Working frequently with very accomplished and versatile cinematographers such as Thomas Mauch and Jörg Schmidt-Reitwein, his films have often displayed a visual tactility and mobility that both befits their often low-budget, improvised nature, and their central thematic functions.

The look of Herzog’s films is part and parcel of the core of his films, not simply an addendum to them. Arguably one of the most underrated aspects of his work, few other directors seem to have an ability to capture astounding and breathtaking images as quickly and as efficiently as Herzog does, something which is all the more incredible considering that Herzog proudly states he has never storyboarded his films, often improvising on set and working from there.

Contrast that with the style of Alfred Hitchcock, who storyboarded his films so thoroughly that he didn’t even need to look through the camera once shooting began, and the guerrilla style that Herzog employs is even more impressive.

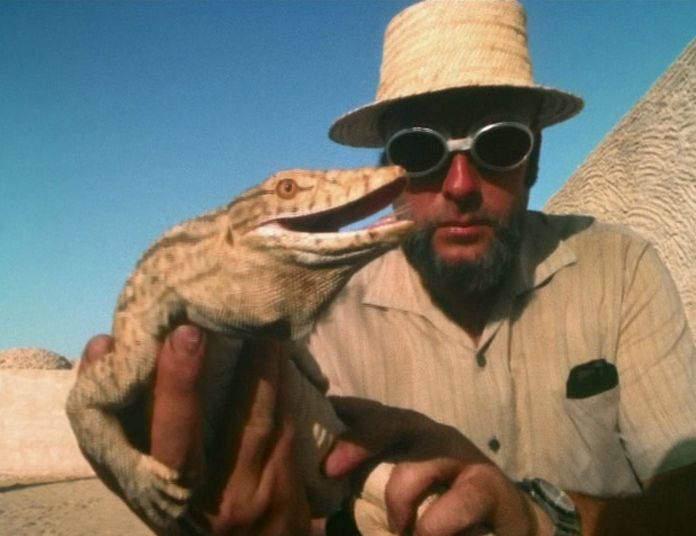

Early works such as Fata Morgana (1971) would not be as ethereally hypnotic without a camera that was happy to roll its eyes over the strange and obscure sites that its operators came across in the Saharan desert. Later, the ever-present sense of the camera being very much part of the proceedings being filmed lends an even more tense sense of authenticity to Fitzcarraldo, as if it needed some more.

Herzog’s cinema repeatedly draws inspiration from things he finds on location. As great as Stroszek (1977) is, it is made all the more great for its inspired final shot, a hypnotised dancing chicken. Some directors dare not include a shot that wasn’t planned. Herzog is quite happy to point his camera at whatever image he feels is fit for purpose. This mobility and connotative ability lends his cinema a poetic quality that few auteurs can match.