7. Blue Collar (1978, Dir. Paul Schrader)

Many of Springsteen’s songs feature working class characters, several of whom are union workers; a classic line from “The River” has the protagonist tell the listener, “For my nineteenth birthday, I got a union card and a wedding coat.” However, it’s more than just union workers who populate Springsteen’s landscape – his union workers are feeling the pinch of the beginning of a globalizing economy, for whom the American Dream is becoming unattainable.

The three main characters of Paul Schrader’s directorial debut – Jerry (Harvey Keitel), Zeke (Richard Pryor), and Smokey (Yaphet Kotto) – are union workers who turn against their labor brothers and decide to rip off the union safe in order to make a quick buck.

Working class men turning to crime out of desperation is a common theme of Springsteen’s music – there’s the protagonist of 1984’s “Working on the Highway,” who ends up in jail after taking off on a road trip with an underage girl, and “Downbound Train,” from the same year, which tracks the decline of one worker from the lumber yard to the car wash to a railroad gang.

The songs (and the film) are about the increasing isolation at the center of American working class life, as Schrader’s characters tear each other apart, pitted against each other through the exploitation of their racial differences and ambition.

8. Dog Day Afternoon (1975, Dir. Sidney Lumet)

Another film that emphasizes the travails of the working class, Lumet’s tension-filled potboiler mixes the social commentary of a man (Sonny Wortzik, played by Al Pacino) turning to desperate measures – robbing a bank – for money, with an almost farcical tone that wrings bizarre comedy out of the incident, based on a real event. Sonny, like many Springsteen characters, is a Vietnam veteran, and suffers without much in the way of gainful employment. That he would turn to crime to keep pace with his needs is a part of the world that Springsteen chronicles.

Though the film was released seven years before, it anticipates a key song in the Springsteen catalog, 1982’s “Johnny 99” from the Nebraska album. The song describes a man named Ralph who “went out looking for a job / But he couldn’t find none” and robs a convenience store. It goes badly, as Ralph is hit over the head by an off duty cop and hauled off to jail.

Much of the song focuses on Ralph’s trial, where he is rechristened Johnny 99 by the judge, who sentences him to “ninety-eight and a year” for his crimes. The song, played acoustically in a rockabilly style, is tonally inconsistent with the anger underlying it; Johnny’s statement to the judge says, in part, “I had debts no honest man could pay / The bank was holdin’ my mortgage and they was takin’ my house away / Now I ain’t sayin’ that makes me an innocent man / But it was more ‘n all this that put that gun in my hand.”

Dog Day Afternoon achieves a similar level of tonal inconsistency, mixing an underlying anger in what is at often times a very comedic story. Each work, despite these inconsistencies, is successful in conveying its working class resentment of economic forces that are beyond the control of their protagonists.

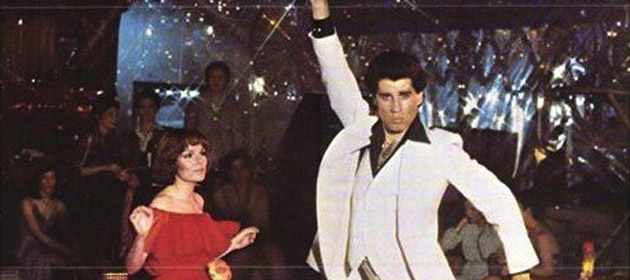

9. Saturday Night Fever (1977, Dir. John Badham)

This film may seem like an unlikely inclusion – after all, it’s primarily known for launching John Travolta to superstardom on the strength of his dancing, and the hot-selling disco soundtrack, the feel of which must sound light years away from Springsteen’s soul-infused rock and roll and introspective acoustic ballads. However, buried beneath the glitz of the disco clubs and the dance moves that have been ripe for countless parodies, this film boasts a story of working class anxiety and dissatisfaction with one’s station in life.

Songs from the Springsteen catalog like “Night,” from 1975’s Born to Run, and “Out in the Street,” from 1980’s The River, tell stories about men who spend all day working jobs that they hate, and find relief from the soul-crushing work only after the sun goes down.

Travolta’s Tony Manero seems ripped from one of these songs – after toiling in the paint store all day, it’s in Odyssey 2001 where he comes alive, the energy of dancing, hustling, and fun that keeps him going. For characters who feel they have no future, the present, at night, is when they have to live. Many other Springsteen songs capture this same dynamic, but they leave the disco to the Bee Gees.

10. Blue Valentine (2010, Dir. Derek Cianfrance)

In many of the songs he recorded for 1980’s The River, Springsteen explores the highs and lows of married life (despite not being married himself at the time). “The River,” “Stolen Car,” and “Wreck on the Highway,” all from that album, each describe characters in restless, troubled marriages; though it’s not easy to pinpoint exactly what’s wrong with either person in the relationship, there’s just something that doesn’t quite feel right.

That’s the case with Blue Valentine, where a general restlessness and dissatisfaction with life seems to have set in over Cindy (Michelle Williams) and Dean (Ryan Gosling), whose marriage we see both coming together and coming apart in a split timeline.

Cianfrance’s reliance on both the past and the present examinations of their relationship shows connection with many of Springsteen’s songs about married people. The lows are made more tragic by the descriptions his lyrics lend to the highs. For example, 1978’s “Racing in the Street” seems like a perfect soundtrack to pair with Blue Valentine.

The first half of “Racing” is the upbeat, youthful point of view of the song’s narrator, who impresses a girl during a street race; the second half is about the gradual decline in their reason for being together, as the narrator describes her sitting “on the porch of her daddy’s house / And all her pretty dreams are torn / She stares off alone into the night / With the eyes of one who hates for just being born.”

Williams’s Cindy seems exactly like this character, as she floats through the present narrative wondering what her life could have been had she not chosen to marry Dean.

11. Badlands (1973, Dir. Terence Malick)

While Springsteen is reputed to have lifted the title of this film for the kickoff anthem “Badlands” on his 1978 album Darkness on the Edge of Town, he also has borrowed the film’s story for his album Nebraska (1982). The album’s title track chronicles the story of Charlie Starkweather and his young female accomplice, who went on a multi-state killing spree in the 1950s. The song is sung in first person from Starkweather’s point of view, and it’s hard to imagine Springsteen not being inspired by Malick’s film.

Both the film and the song are about the alienation of a young man from the culture around him. He is emotionally stunted, as both Springsteen’s protagonist and Martin Sheen’s Kit from the film consistently reference the idea of ‘having fun’ along the road, murders and all. The cover of the album looks like it might have come from Badlands, too, with the empty highway and the horizon ahead. Many of Malick’s shots emphasize the emptiness of the landscape, both on and off the road, strong themes throughout the entirety of Springsteen’s musical catalog.

12. The King of Marvin Gardens (1972, Dir. Bob Rafelson)

The title of this film makes an oblique reference to the board game Monopoly, which takes its property names from Atlantic City, New Jersey, the setting for the story. It’s about two estranged brothers, one a radio host (David, played by Jack Nicholson), and the other a hustler and con man (Jason, played by Bruce Dern), who come together at Jason’s insistence for a business deal. Jason wants to get financing secured for a resort, to be constructed on an island near Hawaii, and he wants David to help him put the deal together.

As a product of the Hollywood Renaissance, it should be no surprise that Jason’s plans are nothing more than a pipe dream, and they, like him, are doomed. An especially evocative thematic connection exists in Springsteen’s “Atlantic City,” from 1982’s Nebraska album. The entirety of Nebraska is often seen as a reaction against the election of Ronald Reagan to the presidency (and his economic policies), and both that album and this film seem to be making the same point – that increasingly, the American Dream seems further and further away.

The hustlers in “Atlantic City” have “debts that no honest man can pay,” and see their only way forward as turning to crime. In both the film and the song, Atlantic City functions as a last-ditch chance for the characters, but they don’t know the game is rigged against them. Just like in the board game that lends the film its title, those with no money are punished.

13. The Indian Runner (1991, Dir. Sean Penn)

First time writer-director Sean Penn steps behind the camera for this film about two brothers – one a farmer turned cop, and another a veteran home from Vietnam dealing with a kind of post-traumatic stress. The idea for this film came from Springsteen’s 1982 song “Highway Patrolman,” a cut from Nebraska.

The screenplay follows the narrative of the song almost exactly, as Penn uses the characters’ names that Springsteen provides: the narrator of the song, Joe Roberts, is played by David Morse, his wife is Maria (Valeria Golino), and his brother, who, in the words of the song, ‘ain’t no good,’ is Frankie (Viggo Mortensen).

Penn gives Joe voice over, during which he describes details from the song, a device that allows Penn’s film to maintain the close focus that “Highway Patrolman” gives to its protagonist. Penn also grabs images from the song’s lyrics and tries to reproduce them in images.

Springsteen’s chorus says, in reference to the two brothers, “There’s nothing better than blood on blood,” and Penn dutifully complies, as he has Joe cut himself and drip blood on a bar counter in an especially confrontational scene with Frankie. Penn also faithfully reproduces the song’s climactic moments, as Joe, pursuing Frankie after he has committed a murder, “pulled over to the side of the highway / and watched his taillights disappear.” The result is a close adaptation of not just Springsteen’s narrative and thematic approach to songwriting, but a near translation of his images, as well.