Nicolas Winding Refn’s Drive seemed to have come out of nowhere; a relatively unknown Danish director directing an art film starring, of all people, The Notebook star Ryan Gosling sounded like a very hit-or-miss premise. Despite having only Gosling’s star power and an enthusiastic film festival reception to back it up though, the film ended up earning six times its budget and quickly achieved cult status (and, in some cases, infamy) among film fans worldwide.

The combination of slick visuals, a soundtrack fueled by pure ‘80s nostalgia, and unexpected bursts of extreme violence made Drive stand out from the pack in 2011; rarely do action movies take themselves quite so seriously and – more shocking yet – maintain such slow, deliberate pacing throughout.

Although it seemed like nothing else at the time, however, Drive is not without its predecessors. Many of its most distinctive elements – the stoic protagonist, the bright neon lights, the heavy doses of moral ambiguity– have been seen in countless other films from around the world. These are ten of the most memorable films that, like Drive, often blur the line between ultra-stylish action movie and coolly restrained art film.

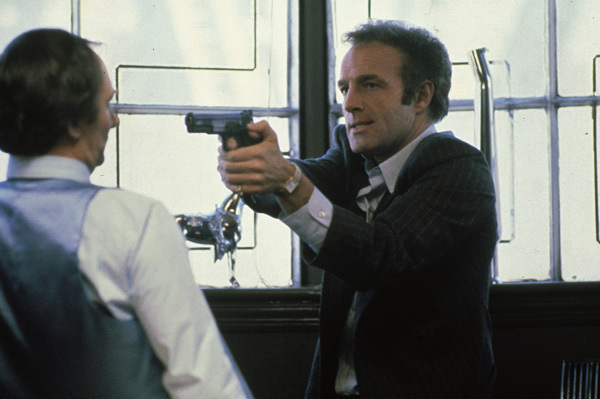

1. Thief (1981, Michael Mann)

American auteur Michael Mann’s tense debut feature is a bracingly bold crime thriller that oozes confidence. All of Mann’s later, better known films are rooted in the seedy neon-lit streets of Thief; the carefully choreographed action and attention to detail of Heat, the ample style and near-constant suspense of Manhunter, and the visual flair of Miami Vice can all be traced back to this underrated (and underseen) heist flick.

James Caan stars as Frank, a master criminal and ex-con who is looking to finally settle down after decades as a freelance thief. His plans to retire are interrupted when the Los Angeles mafia offers him one final heist that could secure him enough money for a fresh start. As Frank soon finds out though, getting out of the game is never that simple.

In case that plot summary didn’t make it clear enough, Thief bears a remarkable likeness to Drive: The two films are both set in Los Angeles, have near-identical plots, and have strikingly similar visual styles that emphasis the dreamy, neon-tinged side of LA nightlife.

The similarities are so numerous that it would be entirely reasonable to suggest that Drive is in essence an unofficial remake of Thief; albeit an unintentional remake, as Nicolas Winding Refn has been quoted as saying that he hadn’t seen Thief until very late into the production of his film.

2. Le Samourai (1967, Jean-Pierre Melville)

Ryan Gosling’s remarkably stoic portrayal of Drive’s nameless protagonist received a great deal of attention from both critics and the general public; Viewers were divided over whether the driver’s lack of emotion and scarcity of words was an effective stylistic choice or simply a frustrating indication of a two-dimensional protagonist.

Regardless of the character’s controversial reception, anyone who’s seen Le Samourai can verify that his detached personality – or lack thereof – is not without precedent.

French heartthrob Alain Delon’s performance in the aforementioned film as master hitman Jef Costello is similarly understated and was a clear influence on the development of Gosling’s character. His character, like Gosling’s in Drive, is a nonverbal yet thoroughly professional criminal with a strict set of rules: in this case the Bushido, the rigorous code to which samurai in feudal Japan were bound.

Though extraordinarily subtle, Delon’s cool and calculated performance has become iconic over time and it is largely what defines Le Samourai as a beloved cult classic today. Master of suspense Jean-Pierre Melville’s remarkably restrained direction goes a long way as well, making this one of the more intelligent and entertaining crime thrillers of the 1960s.

3. The Guest (2014, Adam Wingard)

Relatively new director Adam Wingard’s claim to fame has been through indie horror offerings such as 2011’s home invasion thriller You’re Next and a segment in the 2012 horror anthology V/H/S, but his most exceptional film by far is his most recent: The Guest, a brilliant, bloody homage to the ultra-stylish action thrillers of the 1980s.

While most films that imitate the synth-filled, neon-drenched cinematic aesthetic of the 1980s aim for a tongue-in-cheek angle, The Guest takes a far more earnest stance.

Like Drive, it operates as both a love letter to those neon-drenched thrillers and as a modernization of them, abandoning the more dated elements and breathing new life into the sub-genre; Wingard employs a basic narrative framework typical of uniquely ‘80s films like Manhunter, Dressed To Kill, and To Live And Die In LA – a mysterious stranger enters a suburban family’s home and starts solving their problems by way of extreme violence – then amps up the atmosphere and dread without a trace of ironic distancing, crafting a film that pays tribute to its predecessors while still feeling undeniably modern.

Don’t misconstrue all that praise as an indicator that this is high art, however; The Guest revels in B-movie trashiness and the more pulpy aspects of its plot, making clear its unpretentious goal to serve as pure, unbridled entertainment.

4. The Place Beyond The Pines (2012, Derek Cianfrance)

Although Blue Valentine director Derek Cianfrance’s crime saga The Place Beyond The Pines blurs genre lines over the course of its elliptical narrative, it is first and foremost a thrilling crime drama exploring fathers, sons, and tragic family legacies that are carried from generation to generation.

While Blue Valentine was surely ambitious in its nonlinear documenting of a relationship as it blossomed and then as it deteriorated, jumping back and forth in time to emphasize the tragedy of a relationship doomed to fail, The Place Beyond The Pines takes this ambition to an extreme and paints its story on a broader, more epic canvas; the narrative is divided into three interconnected and distinct acts, each one taking place a few years after the last and with a different protagonist.

The first section of this cinematic triptych, and the one that sets up the narrative for the following two sections, follows Ryan Gosling as Luke, a motorcycle-riding carnival worker who finds out a woman in Schenectady (Eva Mendes) just gave birth to his son.

Having a low paying job and therefore no means of supporting his unexpected offspring, he turns to bank robbery as a means of child support, risking his life to keep his son and the mother of his son financially afloat. His plan goes south fast, and the film tracks the consequences of his crimes as we are shown how it changes the lives of a local police officer, Luke’s son, and the officer’s son over the course of the next two decades.

The film’s narrative scope is so grand that it may have been better suited for a less time-constrained medium like an HBO miniseries, but at nearly two-and-a-half hours it manages to be a surprisingly consistent crime thriller dissecting the ripple effect of a failed father.

5. The Warriors (1979, Walter Hill)

A film with a reputation that far precedes it, The Warriors occupies a well-deserved place in the pantheon of great cult action films. The film, driven by a propulsive synth-heavy soundtrack that could only have been composed on the brink of the 1980s, introduces the viewer to a post-apocalyptic vision of New York City in which martial law rules and the city is divided up into the territories of various street gangs.

The eponymous gang comprises the film’s protagonists, who are framed for the murder of a rival gang leader and must battle their way across the city to reach their home turf in Coney Island.

The film’s ultra-stylish mix of carefully choreographed gang fights and tense drama makes it in many ways a surreal variation on the prototypical gangster film, albeit a much more action-heavy variation. Stylized violence and melodrama abound, it’s a gloriously eccentric thriller that entertains on a primal level.