From the beginning of time, human beings have wondered if the universe has a plan in store for them. We have pondered whether every person is born to fulfill a determined destiny, or if every human can build their future from scratch, depending on the choices they make.

It is true that we are determined by time, space, the laws of physics, and so on. We seem to believe we possess some kind of control over our decisions, and that our personality, preferences and tastes are up to us. We believe that we are conscious and aware of every turn on the tracks on the train of life. However, it’s actually more probable that a clueless blind dog is driving that train, and we’re just along for the ride, thinking our will controls the vehicle.

That’s why philosophers have wondered if the fate of people is conditioned by outside random forces, which shape our lifestyle from the cradle to the grave. The fact that if you weren’t born to those parents, or in that neighborhood, or in a different country or century, your life would have been totally different, makes us wonder if humanity is really free, or if we just collectively act on instinct like biological robots.

Considering that filmmakers tend to be visual philosophers, this list has 10 films that explore this topic, each one reaching different conclusions.

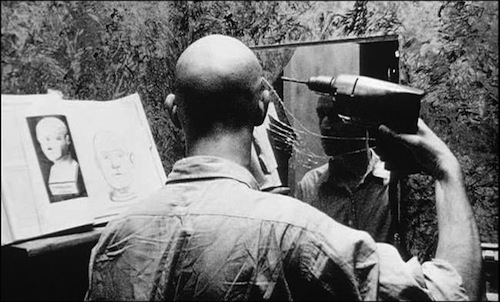

10. Pi (1998)

Max is a genius mathematician, whose search for a unique code to decrypt the patterns he sees all over nature will drive him on a downward spiral to madness.

He spends all day in his small apartment, fixing and adapting all sorts of special hardware, entirely dedicated to finding a magical combination of numbers that will uncover hidden truths about the world. Max is convinced that he’ll discover the key to understanding the universe on a whole.

However, it turns out that a few Jewish researchers are searching for this combination as well; they think it’s the real name of God that can only be found by a chosen one.

So, if Max believes there’s a determined number that can be used to understand the world’s patterns and even predict their outcomes, then free will can’t exist. In that case, human beings would just be following a set of natural rules that organize the universe, maybe obeying divine purposes, like the Jewish researchers in this movie seem to believe.

Max’s positions represent a branch of mathematical determinism that claims that free will is really an illusion. Laws of physics give a compelling diagram of how the world works, without any need for a metaphysical entity governing living things. There are many scientists, especially neurologists, that support this theory.

Wolf Singer is one of the most popular among them; an article he wrote in 2004, claiming that the illusion of “conscious” decisions can be explained by certain processes in the brain, has created controversy and intense discussion.

Do we have free will? No. There’s a natural pattern that predicts every event.

9. Watchmen (2009)

On the surface, “Watchmen” doesn’t seem like a film related to the free will vs. determinism debate.

Zach Snyder isn’t known for his intellectual depth as a director. Thankfully, master comic book writer Alan Moore (the author of the graphic novel “Watchmen” is based on) loves to analyze philosophical matters in his work, much like Batman loves to add thousands of layers of black paint to everything he owns.

In one of the best written chapters of the graphic novel, Moore lets us consider what it would be like to be an omnipresent being. He describes Dr. Manhattan’s perspective of time in a vivid way. This character is aware of every little event that happens anywhere, and at the same time, his memories and future happenings fuse together to provide him with a divine perspective of the world.

In the notable scene where a Vietnamese woman slashes the comedian’s face with a broken bottle just before he fatally shoots her, Dr. Manhattan is present and does nothing to stop this atrocious murder. Considering his godlike powers and firm morality, this doesn’t makes sense until later in the film when Dr. Manhattan confesses that “everything is predetermined, even my responses”.

As an omnipresent and omnipotent being, he knows when and how anything is going to happen, but unless it is already predetermined, he can’t stop any future event simply because he has prior knowledge of it taking place. Paradoxically, he’s also predetermined.

All this references the famous philosophical debate which wonders, if a God already knows what everybody’s going to do before it happens, then could we still have free will? Many philosophers, namely Leibniz, Saint Thomas Aquinas and Saint Anselm, have given different answers to this question. Moore’s answer seems to be that even God is a victim of determinism; he just stands and watches his creations interact without being able to intervene unless is already predetermined to do so. So, in short, everybody is time’s bitch.

Do we have free will? Absolutely not. Even God’s actions are predetermined.

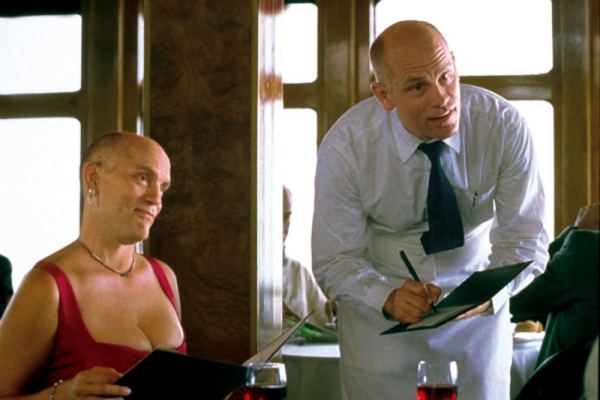

8. Being John Malkovich (1999)

It’s obvious at this point that Charlie Kaufman reads a few books on philosophy before writing a new screenplay. Every movie he has made features several philosophical ideas, which he uses to intrigue his audiences just as those thoughts intrigued him. “Being John Malkovich” proves he can combine these kinds of questions with his trademark comedic style.

Dualists and physicalists have been arguing about the existence of a “mind” or “soul” for ages. This film’s plot seems to support the dualists; they think that a higher immaterial consciousness must exist in living things.

The protagonist in “Being John Malkovich” finds a secret door in his office that leads to John Malkovich’s head. He can see everything from Malkovich’s perspective, and given that the main character is also an expert puppeteer, he’s able to control poor John’s body after a few rounds of practice. This raises some questions: where does Malkovich’s conscience go when he’s being controlled by the puppeteer? How is this man able to see through the eyes of Malkovich without him noticing? Where does our conscience come from, and why are we able to control our bodies?

The film also portrays an interesting fact; when anyone enters Malkovich’s head, they go in with their whole bodies. It’s not just a conscience transfer; their whole physical bodies enter Malkovich’s mind and then exit it after a few minutes.

Does this mean our body is just the manifestation of our consciousness? Or is what we call “consciousness” just a byproduct of our brain’s sophisticated biology? This is not a new issue in philosophy; dozens of intellectuals have debated and even written hundreds of books about it.

Descartes firmly opposed the existence of an immaterial substance that lies only in living things; how can a non-material substance interact with a material one? It’s one of the questions that dualist theories like the one in this film face, although science hasn’t reached the point of pointing to the precise mechanisms of the brain that constitute what we call “free” choices; most scientists prefer the physicalist’s claims.

However, subjective experiences play a big role in “Being John Malkovich”; are the subjects that visit Malkovich’s mind really being John Malkovich, or are they just controlling his body? Then again, isn’t our brains all we really are? Or is there more to a human being?

Do we have free will? Yes, but our body could be invaded by other humans, forcing us to redefine the nature of being.

7. Dead Man Walking (1995)

If we, as a species, don’t really have control over our choices, then how can we blame a murderer for killing people if he’s predetermined to do so? Why should we blame anyone if our choices depend on hundreds of external factors that we have no control over? “Dead Man Walking” deals with all these questions wonderfully, telling the story of an inmate sentenced to death by lethal injection as he copes with guilt, denial and anxiety.

Susan Sarandon plays a nun trying to save a criminal (Sean Penn) from imminent execution; she believes he might be innocent, or at least worthy of a lighter form of punishment. Her character interrogates the imprisoned to find out the facts about what he’s accused of doing. He claims he was drugged at the time, and that he also hadn’t slept for two days. Penn’s character blames his partner for having committed the crimes; he just stood and watched as he murdered a young man and his girlfriend.

The nun’s attempts to spare him are unsuccessful, so she chooses to convince the criminal to accept his guilt in the matters. He may have not killed anyone; however, he was an accomplice and did nothing to stop the crime. In the end, he comes out of his denial and admits that he was more involved in the events that he wanted to recognize.

All of this relates to Peter Strawson’s famous article about free will and morality, titled “Liberty and Resentment”.

He claims that we don’t need to know if free will exists, and to not be confident about the correctness of our morality and legal system, because there are a series of feelings that humans experience (as the parents of the murder victims in the movie represent) when injustice is perpetrated, which validates our moral and penal practices.

Strawson also claims that criminals must be punished without victimization, meaning that they should be judged according to their actions and held accountable, regardless of whether they claim to have been mentally incapacitated at the time. The vandals should recognize their guilt if they want to be considered equal to their peers; if not, they should be isolated from the rest of society.

Sarandon’s character approaches these concepts from a religious perspective that is very similar to Strawson’s view. If somebody wants to be remain a part of society, they must admit their doings were reprehensible. She finally accomplishes this under the pressure of his quickly approaching execution. The movie also comments on the negative sides of the death penalty and how a life sentence could grant inmates the time to think about their terrible actions.

Do we have free will? It’s not clear, but regardless of this, our legal system must continue functioning by presupposing the existence of “freedom to do otherwise”.

6. Waking Life (2001)

If I were to explain this movie to a fellow “film scholar”, I would describe it as a “philosophical clusterfuck”. Director Richard Linklater seems to be a philosophy fan, so he seized the opportunity to portray all his doubts and questions about life and existence in a single chaotic movie, in which a bunch of insufferable pseudo-intellectual individuals poorly explain famous philosophical issues. However, a few of these series of ramblings are interesting for the purposes of this article.

A philosophy professor describes Sartre’s ideas about free will and personal responsibility; he says that when postmodernists describe human beings as a confluence of forces or a social construction, the individual gets to play the part of victim of the universe, not really choosing who he is.

Sartre thinks that every human chooses to be what it is, and that everyone is always capable of changing and becoming something else. Here lies the concept of “angst”, defined as the pressure and anxiety one feels for being able to decide at every turn and at the same time, being an example for all humanity.

The second point of view argues that human beings must be governed by the same physical deterministic laws that reign over everything else. As we are physical bodies, all our actions correspond to a determined physical formula, which really makes us doubt the existence of free will.

As you see, this film is more a series of lectures or a long podcast than it is a movie. Linklater didn’t care about subtlety or illustrations of philosophical thoughts, he preferred to film a group of people lecturing the main character about all sorts of issues. This proves to be tiring, but is useful as a philosophy 101 lesson. As a film? It doesn’t hold up.

Do we have free will? It is undetermined; this film tries to start a debate about it, but doesn’t offer a cohesive answer or even a narrative.