Doppelgängers, doubles, and evil twins. Such notions have been a feint of storytelling for centuries. Shakespeare explored it in “The Comedy of Errors”, as did Alexandre Dumas in “The Man in the Iron Mask”, and both Dickens’ “A Tale of Two Cities” and Poe’s “William Wilson” exploited the idea just ahead of Dostoevsky’s famed and oft-adapted novel, “The Double”.

There’s something intrinsically fascinating with twin tales, often they involve morality narratives, or rivals in an ego-versus-id dynamic, or, in a more sinister vein, evil twins working to replace one another.

In mythology it was often believed that doppelgängers were trickster archetypes, always up for a little mayhem, whereas some folktales viewed supernatural attributes to the idea of doubles. These more disquieting accounts often involved the paranormal, such as the fetch, a duplicate that boded bad omens and often death.

The following list is by no means definitive but it certainly contains the finest examples of cinematic doppelgängers you’re likely to find. Proceed with caution and your wits gathered around you, for it’s easy to be deceived by a duplicate.

30. Partner (1968)

While not considered one of Bernardo Bertolucci’s major works, Partner is still a confrontational and unexpectedly resonant picture. Sure, it wouldn’t be the film to bump Bertolucci out from the shadow of the generation of Italian directors that came before him; Fellini and Antonioni, but it would set him on that course (and be soon followed by The Conformist in 1970 and Last Tango in Paris in 1972, amongst other significant works unleashed at a lightning pace).

Though not explicitly stated, Partner owes much of its narrative to Dostoevsky’s The Double, and tells the story of a young idealist, Giacobbe (Pierre Clémenti), who has a psychotic look-a-like that just so happens to be a political revolutionary. Clémenti’s struggles with bourgeois society seem filtered through a prism of student radicalism, no doubt a reflection of the May 1968 riots in Paris that were going on during shooting.

Partner’s fragmented and declarative leanings, combined with political commentary of a post-nouvelle vague ilk speak to Jean-Luc Godard’s influential style — Bertolucci was always an admirer — and make for a lyrical and Brechtian approach that arthouse audiences will adore.

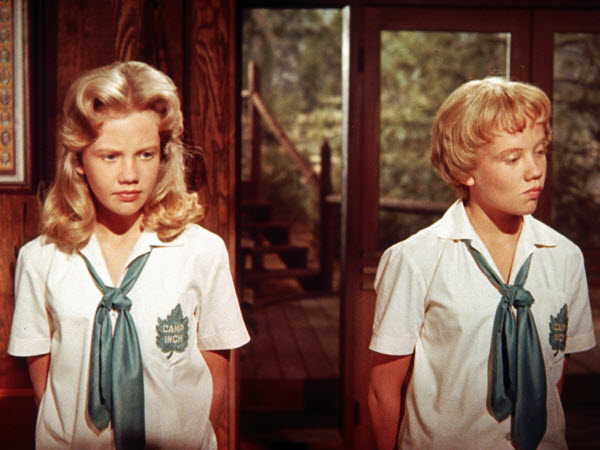

29. The Parent Trap (1961)

This esteemed Disney film, somewhat of a classic for the generation that grew up watching it in theaters and later on television in the 1960s (it spawned no less than three made-for-TV sequels and a 1998 remake), stars Hayley Mills in her most recognizable role(s) as identical twins Susan Evers and Sharon McKendrick.

When the two girls meet at a summer camp, neither one knowing they are actually sisters. After some initial rivalry they soon learn the truth and also uncover that their parents separated when they were born, and they concoct a scheme to reunite them, in an attempt to rectify their family, Disney-style.

The Parent Trap was based off of Erich Kästner’s novel Lottie and Lisa, and the film works primarily because of Mills doting, droll, and palpable performance as well as the demonstrable nostalgia factor, which makes The Parent Trap a rather ravishing throwback.

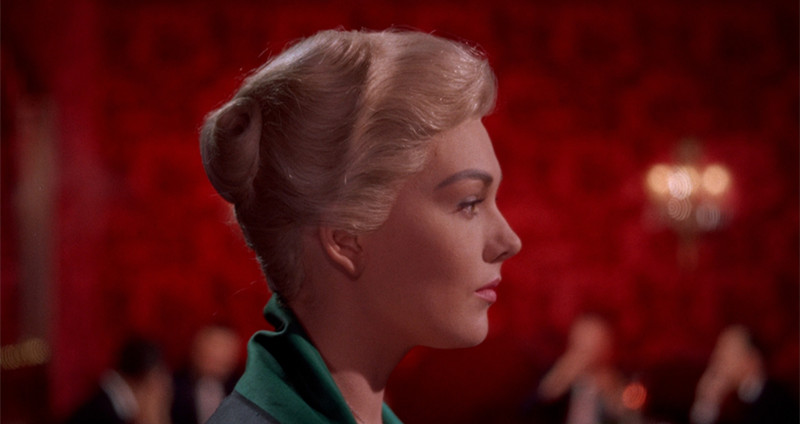

28. That Obscure Object of Desire (1977)

This was the lion of the Surreal movement, Luis Buñuel’s final film, and, true to the tenor of Surrealism, he eschewed any outright rationalization as to why he cast two impressive actresses in the role of Conchita.

Both French ingenue Carole Bouquet and Spanish starlet Angela Molina take turns, seemingly at random, as the temptress Conchita, without rhyme or reason, in a film flush with intentional inconsistencies, usually of a macabre nature, as when an earthshaking car bomb detonates in the background of a scene, and is matter-of-factly ignored in the face of unfolding minor melodrama.

That Obscure Object of Desire was derived from the frequently adapted 1898 novel by Pierre Louÿs, The Woman and the Puppet, perhaps most famously made into Josef von Sternberg’s The Devil is a Woman with Marlene Dietrich, but the idea of having Conchita be a simulacrum prorated between two very different looking leads is purely Buñuel’s invention.

It’s a great risk that succeeds. whereas the audience easily and swiftly forgets that two actresses share the same character in the film Vincent Canby of The New York Times said “creates a vision of a world as logical as a theorem, as mysterious as a dream, and as funny as a vaudeville gag.”

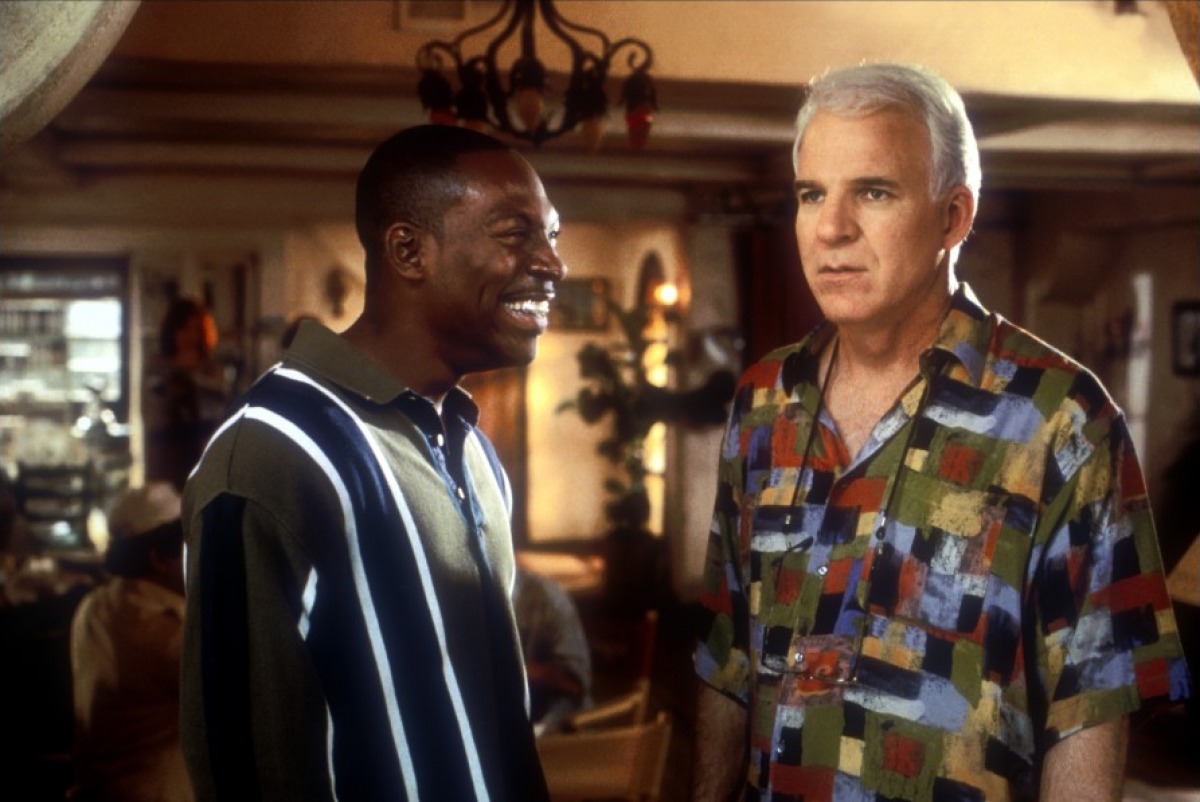

27. Bowfinger (1999)

After some lamentable mid-career stooping, Bowfinger is a good-humored return to form for leads Steve Martin (who also wrote the script) and Eddie Murphy (who, despite a strong cast, still manages to steal the show in a dual role).

In the titular role as a poverty row producer, Martin is Bobby Bowfinger, out to make his next misfire, a cliché-addled actioner called “Chubby Rain”, only this stinker needs a star. Bowfinger finds an obliging yet dopey fellow named Jiff (Murphy), who’s a dead ringer for A-list action star Kit Ramsey (Murphy, again), to star in his film and some sure-fire hilarity ensues.

Bowfinger is a frequently delightful film, one that roasts celebrity culture, ribs mean-spiritedly at Showbiz, and even jabs at indoctrinated religious cults (Kit belongs to a Scientology-like cult called “MindHead”), all while presenting a game cast of comedians in sportively self-absorbed splendor.

26. Lost Highway (1997)

Lost Highway is a pitch-black compendium of the usual off-kilter themes and fixations we’ve come to expect from American auteur David Lynch. The rather Byzantine byway that Lost Highway takes the viewer down is, it must be said, a detour that includes frequent false starts, amounting to only a half-great film.

Perhaps more than any other work, this neo-noir may be Lynch’s most divisive movie, as it offers little elucidation as we follow convicted murderer and sultry saxophonist Fred Madison (Bill Pullman), who, at about the center of the story, becomes auto mechanic Pete Dayton (Balthazar Getty), in a ill-lit mystery involving voyeurism, deviant sex, betrayal, a lot of Rammstein, surreal arrangements, a devilish Mystery Man (played with blood-curdling bravado by Robert Blake), and femme fatales in profusion.

Not only is there a bizarre twinning between Fred and Pete, but dangerous dames Renee Madison and Alice Wakefield (both played with aplomb by Patricia Arquette) may be one and the same.

Lost Highway opens up plenty of space for interpretive discussion, after all, Lynch is forever merging avant garde and populist ideas into highly anticipated experimental cinema, and this complicated, hallucinatory, and subversive nightmare is no exception.

25. The Tenant (1976)

Roman Polanski’s oft overlooked phantasmagorical fever dream, The Tenant, uses many horror-movie conventions to turn everyday life into a Grand Guignol procession into the void. As the eponymous tenant, Polanski casts himself as Trelkovsky, an outsider newly relocated to a Parisian apartment house.

Based on Roland Topor’s novel, Le Locataire Chimérique, The Tenant takes psychological dread, and emotional stability to extremes, making for nerve-racking, bleakly comical infirmity as Trelkovsky’s new neighbors are an odd assortment of freaks and eccentric shut-ins (Isabelle Adjani, Melvyn Douglas, and Shelley Winters are great in their garish roles).

Within the crumbling confines of an old and spooky building, one believably cursed with the spectre of suicide and perhaps something more, Trelkovsky’s growing panic is palpable. Without spoiling any supple surprises, let’s just say that the film engages potential impersonators along with an ending that’s as cruel, and jet-black as can be.

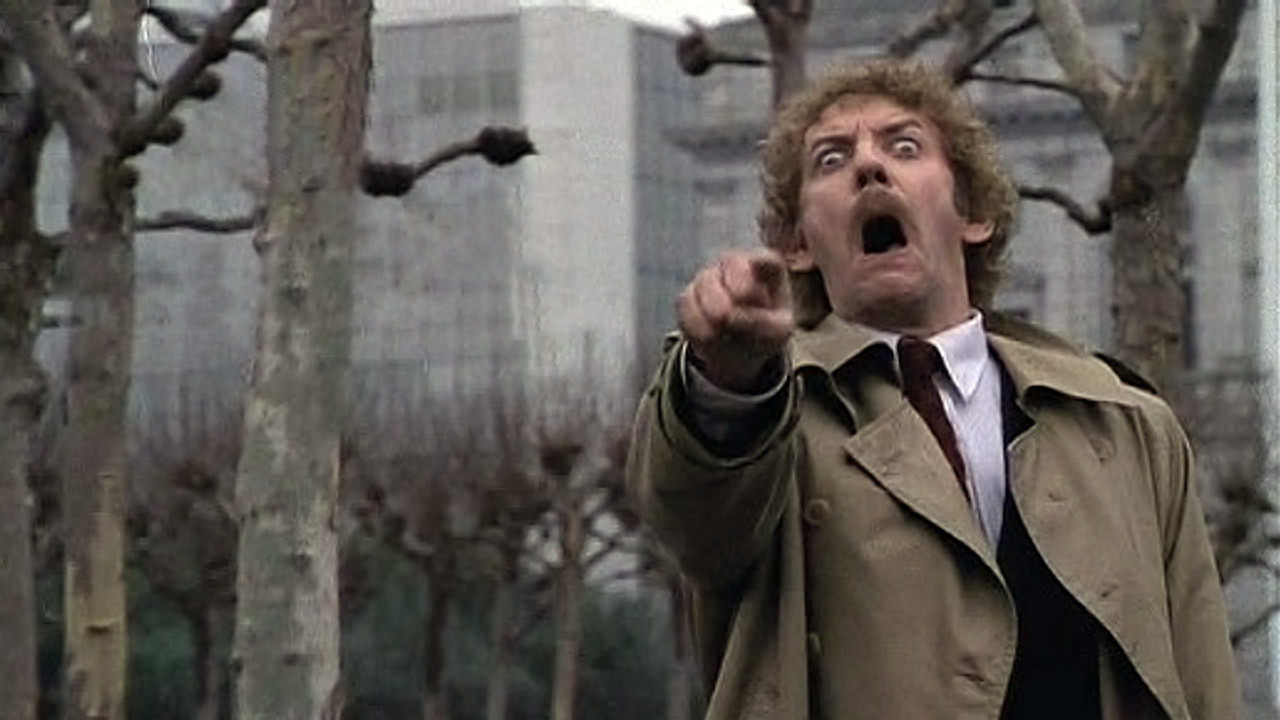

24. Invasion of the Body Snatchers (1978)

Philip Kaufman‘s paranoiac thriller runs on primordial fear and makes the familiar into the most terrifying. While not the first time Jack Finney’s novel was adapted — directors as diverse as Don Siegel (1956), Abel Ferrara (1993), and most recently Oliver Hirschbiegel (2007), have each offered variants on the material — it’s widely considered that the Kaufman version is, if not the definitive, certainly the most redoubtable.

Matthew Bennel (Donald Sutherland, superb), a San Francisco health inspector, begins to suspect that people are being replaced by alien duplicates, pod people, void of emotion.

Aided by W. D. Richter’s jewel of a screenplay, an A-list cast (including Brooke Adams, Robert Duvall, Jeff Goldblum, and Leonard Nimoy amongst others), gorgeous lensing by cinematographer Michael Chapman, and Kaufman at the top of his director game, the results are resounding. The heart-stopping ending offers up a startling and lasting jolt in classic of overly suspicious 1970s cinema.