6. Spencer Tracey (Guess Who’s Coming to Dinner)

Guess Who’s Coming to Dinner’s provocative premise, one which resonates to this day, bestows it the status of a memorable classic, which nominated for ten Academy Awards, winning two. Much of the conflict surrounding whether a black man and white woman could possibly marry – even a couple so well-bred, educated and articulate as John Wayde Prentice (Sidney Poitier) and Joey Drayton (Katherine Houghton) — is embodied in Spencer Tracy’s final, Academy Award nominated performance before his death.

Given only a day to adjust to the notion that his daughter plans to marry the man she met a mere ten days prior, Matt Drayton (Tracey), a newspaper publisher, goes through the gamut of befuddlement and confusion, indignant rage and fear.

Tracey’s co-star (and real-life lover) Katherine Hepburn plays his wife, Christina. Despite initial shock, she becomes sympathetic to her daughter’s desire, though her husband struggles to reconcile his feelings. The situation becomes tenser, and racial attitudes are tested, when the intended groom’s parents come over to the Drayton’s for dinner.

Though ostensibly a light comedy with a dramatic premise, Guess Who’s Coming to Dinner deserves praise for tackling race in an era where black people still fought for civil rights, and even the notion of an interracial marriage was unheard of — even illegal, in some states, as Tracey points out. William Rose took out an Oscar for the screenplay, which gives Tracey plenty of scope, despite some signs of his ailing health.

A standout scene, for example, where a frustrated Drayton accidentally backs into a black man’s car is played for ironic laughs. Despite his struggle to accept, you can still feel empathy towards this doddering old man caught up in an extraordinary situation; having his apparently liberal-minded attitudes put under the heat.

The scene where Drayton argues with the Monsignor – stricken by his angry refusal to accept the marriage — while getting dressed for dinner (ties falling off the rack and nearly destroying his sock drawer) – is amusing and quite endearing. Tracey makes us feel frustration at Drayton’s stubbornness; then leads us to feel sad for him.

Ultimately, in a well-written and lengthy monologue at the finale, Tracey wonderfully makes us feel pride in a man who’s faced his own prejudices and fears, and has finally discovered that they will never be as powerful as love.

5. John Wayne (The Shootist)

John Wayne, immortalised as “The Duke”, was the greatest star of the Western genre; nobody could lay claim as a bigger icon in Western cinema; not even Clint Eastwood, who made a great impact in Sergio Leone’s Spaghetti Westerns, but often starred in films outside the genre. Wayne simply owned Western movies throughout his illustrious career.

The Shootist, Wayne’s cinematic valedictory, is all about a man who’s unable to live down his fierce reputation, despite the fact that he hasn’t got much longer to live. The ironic parallels between The Shootist’s protagonist, JB Book, and the film’s larger-than-life star are particularly poignant.

Wayne is absolutely wonderful; full of stoic integrity, guts and power. Diagnosed with cancer, the feared gunslinger, JB Book, seeks refuge in lodgings owned by landlady, Bond Rodgers (Lauren Bacall) to live out his final days on his own terms. Although director Don Siegel (who also directed Clint Eastwood in Dirty Harry) assembled a superb, star-studded supporting cast, including Bacall, Ron Howard, Scatman Crothers and “Special Guest” James Stewart, Wayne engulfs the film with his commanding performance.

After completing The Shootist, Wayne’s death from cancer the year after imbues the film with an added level of emotion; here was a seemingly indestructible hero of Western cinema – renowned for playing morally complex gunslingers – struck down by the same disease that cripples JB Book with bouts of pain.

The Shootist’ climactic gun fight is a fitting send-off for The Duke, guns blazing in his final moments on-screen; determined to ride off into the sunset having delivered a truly memorable final performance.

4. Richard Farnsworth (The Straight Story)

Nobody expected surrealist director, David Lynch, to deliver one of the purest, simplest and kind-hearted films of the 90s. Departing from a career making censor-baiting, avante-garde films – among them, Eraserhead, Wild at Heart and his most controversial, violent classic, Blue Velvet, where antagonist Dennis Hopper’s outrageously sexual psychopath huffed nitrous oxide and physically and emotionally abused Isabella Rosellini — nobody could have expected The Straight Story to be exactly that: a straightforward, and extremely moving and gentle portrait of a man on a quest to make amends with his dying brother.

Based on an amazing true story, the film is about Alvin Straight (Farnsworth), a lifelong Nebraska farmer whose journey on a ride-on mower across America – intent on reconciling with his dying brother – is heartfelt and emotional. The sheer force of the film comes from Farnsworth’s subtle, internalised performance; a wellspring of grief and the quiet, salt-of-the-earth determination of a country man with a very singular purpose; in spite of the incredulity of the townsfolk.

Farnsworth received an Academy Award nomination (among several award nominations) for this, his final great work. Alvin Straight’s integrity and purity as a character is a fitting final testament to Farnsworth – a film journeyman who will forever be remembered for his laconic, genial and forcefully unfussy onscreen presence.

3. Henry Fonda (On Golden Pond)

Mark Rydell’s comedic drama set at a family’s lake-house overlooking the titular golden pond is boosted immeasurably by Fonda’s brilliant and poignant final feature performance. On his eightieth birthday, prickly and acerbic patriarch, Norman Thayer (Fonda), expects his impending death to come at any moment, much to the annoyance of his wife, Ethel (Katherine Hepburn).

Having been married for over fifty years, the bond between husband and wife is strong, despite his constant jibes and her nagging. Among the affectionate squabbles, Norman feels deep insecurity about his ailing mental faculties. The past and memory casts a thematic shadow over the film.

Norman’s daughter, Chelsea (Fonda’s real-life daughter, Jane) — who Norman feels abandoned him and his wife to live in Los Angeles with her dentist boyfriend (Dabney Coleman) and his teenage son (Doug McKeon) — is full of resentment over what she remembers as a difficult childhood with a loving mother but emotionally distant father.

Originally James Stewart wanted to star in On Golden Pond. However, when Jane Fonda purchased the film rights, she convinced her father to take on the role. Given the real-life tension that existed between them at the time, this must have been a cathartic experience, and their strained onscreen relationship is emotionally bruising to watch.

This is only the second time in history (after Ryan and Tatum O’Neil in Paper Moon) that father and daughter appeared in the same movie. One of the final scenes between Henry Fonda and his daughter crackles with emotion: “I just want us to be friends”, Jane says to her father, tearfully. It’s an especially powerful note – a final cry for peace, in the twilight of Henry’s life.

While On Golden Pond’s Oscar-winning screenplay (adapted by Ernest Thompson from his play) is talky, and the film is dated, there’s no denying its star power. Henry Fonda and Katherine Hepburn (whose performance is actually hard to take at times; her difficulties from a neurological disorder similar to Parkinson’s Disease were ironically far more pronounced than Henry’s illness) won Oscars; although Fonda’s portrayal of Norman is most superb.

From Norman’s tentative bonding with the teenage boy on fishing trips; to the subtle moments of fragility as he realises his mind is failing – “You won’t be able to leave me alone for long”; and his sarcastic and acidic barbs at Chelsea’s boyfriend, Fonda’s final bow leaves an indelible impression.

2. Heath Ledger (The Dark Knight)

In The Dark Knight Ledger elevates the villainous clown, The Joker — Batman’s most iconic nemesis — to the level of Grand Guignol; macabre and psychotic, yet compellingly charismatic. Jack Nicholson’s first live-action iteration of The Joker in 1989 was broadly comic; perfectly suited to director Tim Burton’s Gothic flourishes.

But steeped in post 9/11 paranoia, in Christopher Nolan’s, The Dark Knight, The Joker is the face of terrorism; and what a face indeed: wide gashes scarring his mouth in a ghastly smile, smeared blood red; cracked ghost-white makeup and black-smudged eyes; a shock of ragged, badly dyed green hair.

Ledger crafted his Joker during an intense month holed up inside his New York apartment. He experimented with voices, the Joker’s iconic, maniacal laugh and walk. The result is vivid and spine tinglingly unpredictable and founded in a variety of influences: from Charlie Chaplin’s halting, splayed-toed walk to The Joker’s stooped and rounded shoulders (pure gangland heavy; a subtle way to evoke physical power despite his slight frame).

Ledger lips smacks and leers like a lascivious dog; at one point, he even sticks his face out a car window and embraces the wind. The primal, animalistic force of his performance is electrifying and shockingly entertaining. Though as instinctive and anarchistic as The Joker is, he’s fiercely intelligent, and the battle of wits with Batman – the duality of The Joker’s clown mask, hiding the freakish devil inside, and Batman’s mask hiding bubbling rage and the latent potential to become a murderer – is psychologically compelling.

Playing the dark, psychologically damaged Joker so consumed Ledger that he succumbed to an accidental drug overdose just after completing The Dark Knight. He was just 28 years old. Though Ledger began production on Terry Gilliam’s The Imaginarium of Doctor Parnassus, The Joker is his final complete performance. Ledger won a posthumous Oscar for his extraordinary work; a historic feat for a performance based on a comic book character.

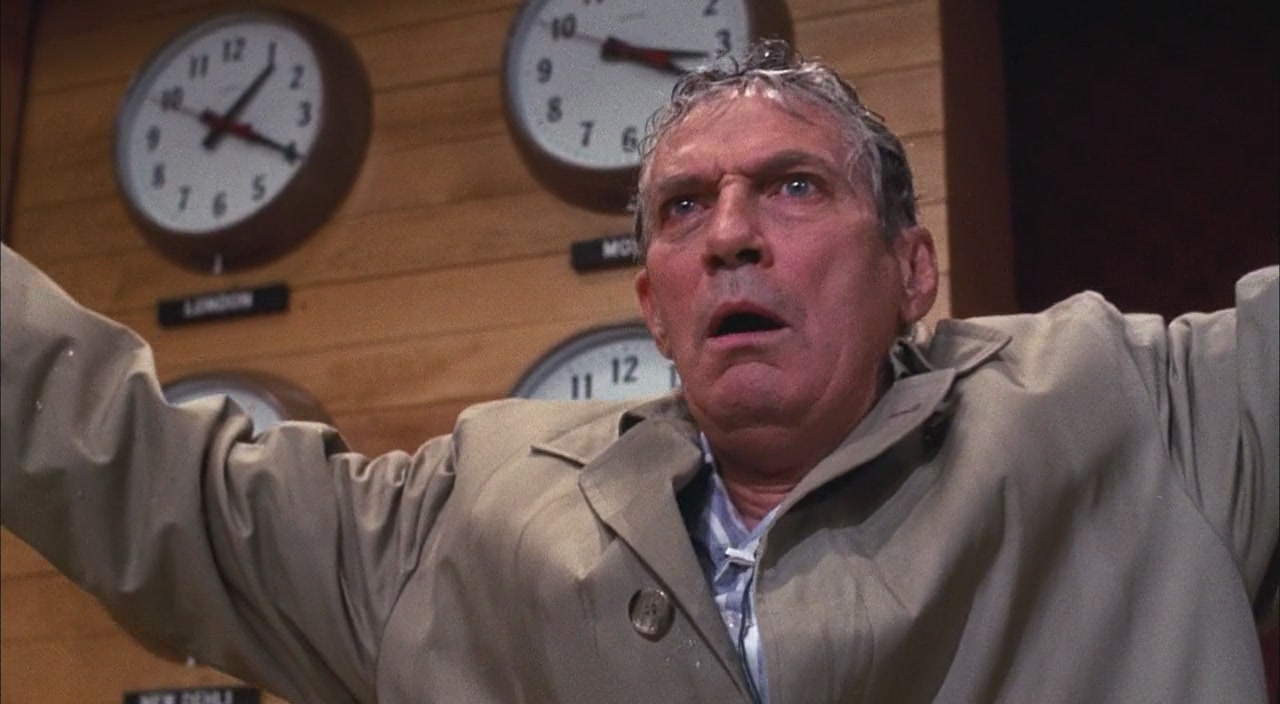

1. Peter Finch (Network)

In Sydney Lumet’s excoriating satire on the cult of television networks, Australian Peter Finch gives a superb, Oscar-winning performance; posthumously awarded. Network is possibly the greatest film about the television industry and the nefarious, opportunistic characters that populate network television.

Howard Beale, a longstanding news anchor is fired because of falling ratings and the changing, corporatized structure of the network, UBS. Loyalty and service mean nothing to corporate interests and Beale’s raging sense of injustice manifests as a “moment of clarity. Not a breakdown; something the Hindus call Prana”.

In his final episodes on air, Beale announces his intention to commit suicide live on television. The resulting spike in ratings conveys the cynical message of Paddy Chayefsky’s brilliant screenplay; give the people death, danger, scandal – anything to distract from the real social ills befalling them every day – and the cult of television tightens its strangle-hold on manipulated minds.

Smelling money, UBS exploits the ratings surge, anointing Beale the “mad prophet of the airwaves” and giving him free rein to explode his raving sermons about society’s greed and avarice on a brainwashed and television hungry public.

Finch burns up the screen and his “mad as hell!” speech is one of the most quotable in movie history. His is one of the most unforgettable, hilarious, heartbreaking and wise final performances ever committed to film.

Author Bio: John Catania is a professional freelance film reviewer, who has written for a variety of street press, online and print publications. Currently, John contributes to Empire Magazine Australasia. He is the founder of “reviews from the chair” – film reviews and movie news – on Facebook.