5. Heavy Metal (Gerold Potterton, 1981)

It was so very tempting to name the prior entry Wizards as a fourteen-year-old geek’s ultimate gift of a quest/adventure tale, but then one would be wasting the kind of comment that is solely responsible for formatting any kind of defence or justification surrounding the existence of Gerold Potterton’s Heavy Metal.

The sheer level of accuracy and perfection in Heavy Metal as a piece of fan service and sci-fi inspired soft-core pornography left me unable to name it anything less than fantastic.

Heavy Metal is not to be appreciated as a coherent, standard narrative. Instead, rather, imagine a series of your recurring school daydreams have been captured and are being displayed on a reel: Heavy Metal, were it not set in a multitude of utopias and dystopias alike, would be a fully authentic document in the study of the modern male adolescent mind.

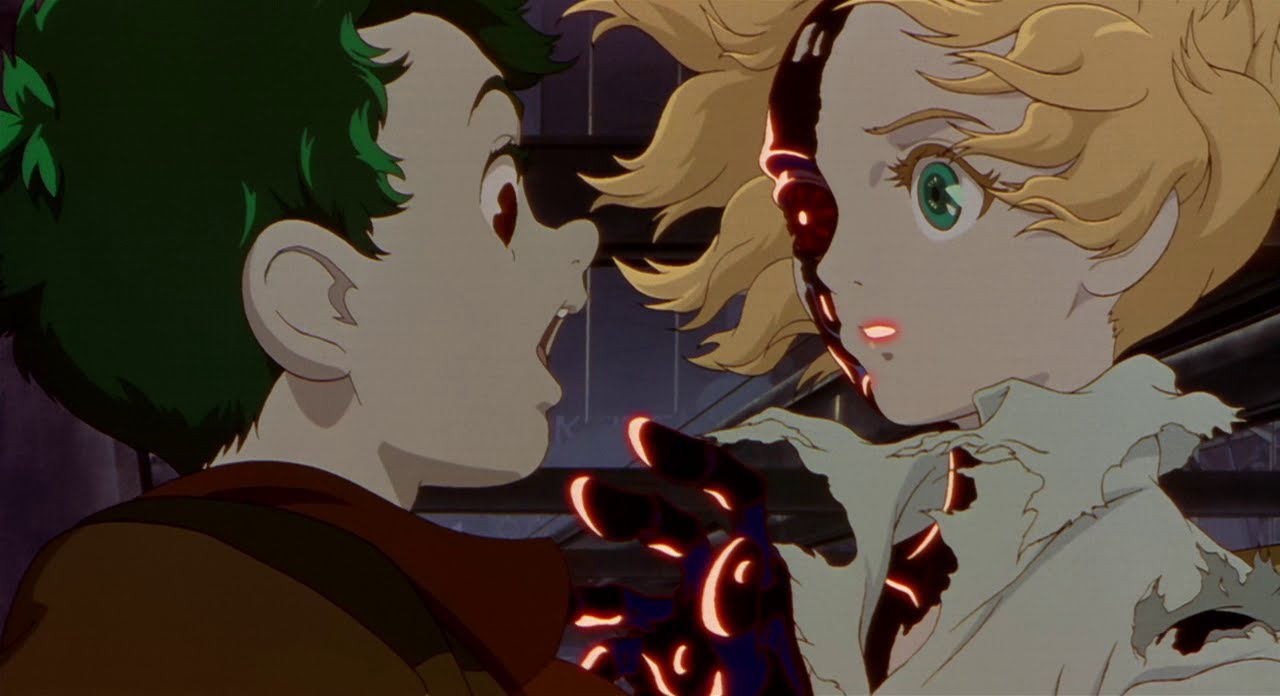

4. Metropolis (Rintaro, 2001)

This Japanese rendition of Fritz Lang’s landmark 1927 masterpiece is not a remake; so much as it is a narrative delving in such blatant similarity it would be wiser to market it as a reimagining rather than the focal point of a lawsuit.

It does feel like a remake, of course. That is, we would recommend it (highly) to the uninitiated, particularly those not well versed in anime productions, by referring to it as ‘Metropolis remade by Miyazaki.’

That reference is used slightly begrudgingly, as neither source is where this film can cite its origin. Rintaro’s ‘Metropolis’ is based not on the German Expressionist grandeur of the same name, but instead on a 1949 manga inspired by Lang’s classic by Osamu Tezuka, the Japanese equivalent to Walt Disney.

As for the name-dropping of craftsman, using Miyazaki to describe the style of Rintaro wouldn’t be inaccurate, but still insulting, considering the career of Rintaro has extended back from 1958, when he worked under Tezuka himself on feature films at the age of 17. Rintaro has had more than enough time to establish a style, distinction, and handbook of traits to call his own (although with ‘Metropolis’ in particular, he held a desire to, ‘communicate Tezuka’s spirit’).

Although one who is familiar with the Lang film might believe this version has nothing new to offer, there is much special, notable, unique memorable content to celebrate in Rintaro’s film. His version is a film more focused on a straight-up adventure narrative, which is chock full of events, happenings, and tonal shifts, than looking for a means with which thematic content might be delivered. The 2001 edition of the story contains a divide between human and mechanical detectives, familial drama, scores of bright, vivid colour, and a heavy showcase of fantastical machinery, technology and zany, possibly impractical, gadgets.

One of the most fulfilling, satisfying and grand sci-fi narratives to ever grace the silver screen is an apt description of Rintaro’s work, one unique to it in opposition to the other, which primarily prides itself on sound, vision and technical proficiency in regard to its aesthetic endurance (on top of major historical significance). Of course, no one is out to claim Rintaro crafted a product that was the superior of Lang’s (on the contrary, if one were to be bothered to make a comparison), but instead one that isolated facets of its prowess in order to originate something fresh, inviting, and thoroughly exciting.

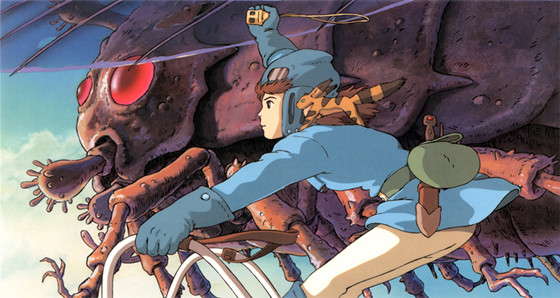

3. Nausicaa of the Valley of the Wind (Hayao Miyazaki, 1984)

Now, we get to the household legend, or at least the closest thing manga/anime has to a regular name-drop in the West. Thank whatever shaped Miyazaki’s tastes and interests for his lack of interest in sci-fi features; otherwise, this list would surely be cluttered with his contributions to the genre.

His sole dabbling in the bracket is, arguably, much like Bakshi’s Wizards, more identifiable with fantasy, but for the opposite reasons: parallel narrative traits. Nausicaa of the Valley of the Wind takes place in a distinctly sci-fi post-apocalyptic wasteland, featuring a people mastering new technology in an attempt to survive the toxic jungle that has seen fit to choke the industrial world into a primitive clutter of kingdoms and tribes with mixed, often selfish, intentions for survival and perseverance.

The thematic content, however, concerning a chosen one, the resultant hero’s journey, and a conflict between kingdoms, seems like a fairy tale. This is contrary to Wizards, which employed a fantasy setting and backdrop to tackle sci-fi thematic content.

It is easy to accuse many a ‘chosen one’ sci-fi or fantasy narrative of taking its substance from either The Lord of the Rings or Star Wars, but notable stylistic influence within ‘Nausicaa’ is drawn from Frank Herbert’s ‘Dune’ universe, namely the storyline’s focus on gargantuan worms whose mood solely decides the living conditions of the nearby populace (and the protagonist riding them near the tale’s conclusion!).

For 1984, this picture’s animation is breathtaking. The oldest animated film whose existence as a showcase of excellent artwork one could believe or claim originated within the twenty-first century is, possibly, this, Miyazaki’s second feature film. Even more impressive, despite an entire catalogue and visual splendour amongst Hayao’s resume, Nausicaa still stands as one of the most eye-catching and appealing of all his crafts.

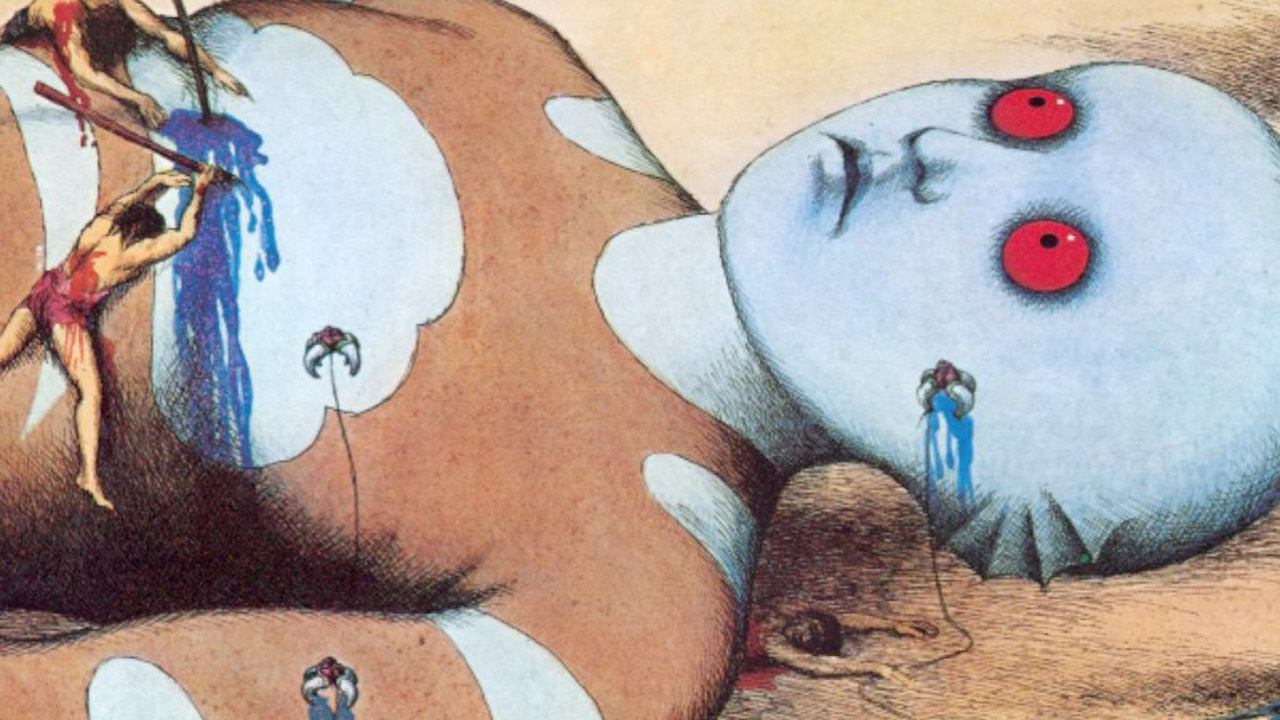

2. Fantastic Planet (Rene Laloux, 1973)

This surreal, psychedelic, unforgettable possible masterpiece was intended as an unclear allegory toward the Soviet occupation of Czechoslovakia.

Of course, cultured drug users found another reason behind its value and artistic merit.

Further still, cinephiles were heavily drawn to this animated oddity, this boldly unique picture that boasted one of the most colourful, innovative celebrations of imagination ever committed to any kind of celluloid or moving picture.

What the likes of James Cameron attempted to achieve with Avatar, the absolute immersion and discovery of alien worlds and cultures, had already been masterfully accomplished within the bizarre beauty that encompasses Fantastic Planet.

And who can ignore the soundtrack by Alain Goraguer, a mix of synthesized psychedelic rock, funk instrumentation, a passionate flutist, and electronic ambient harmony?

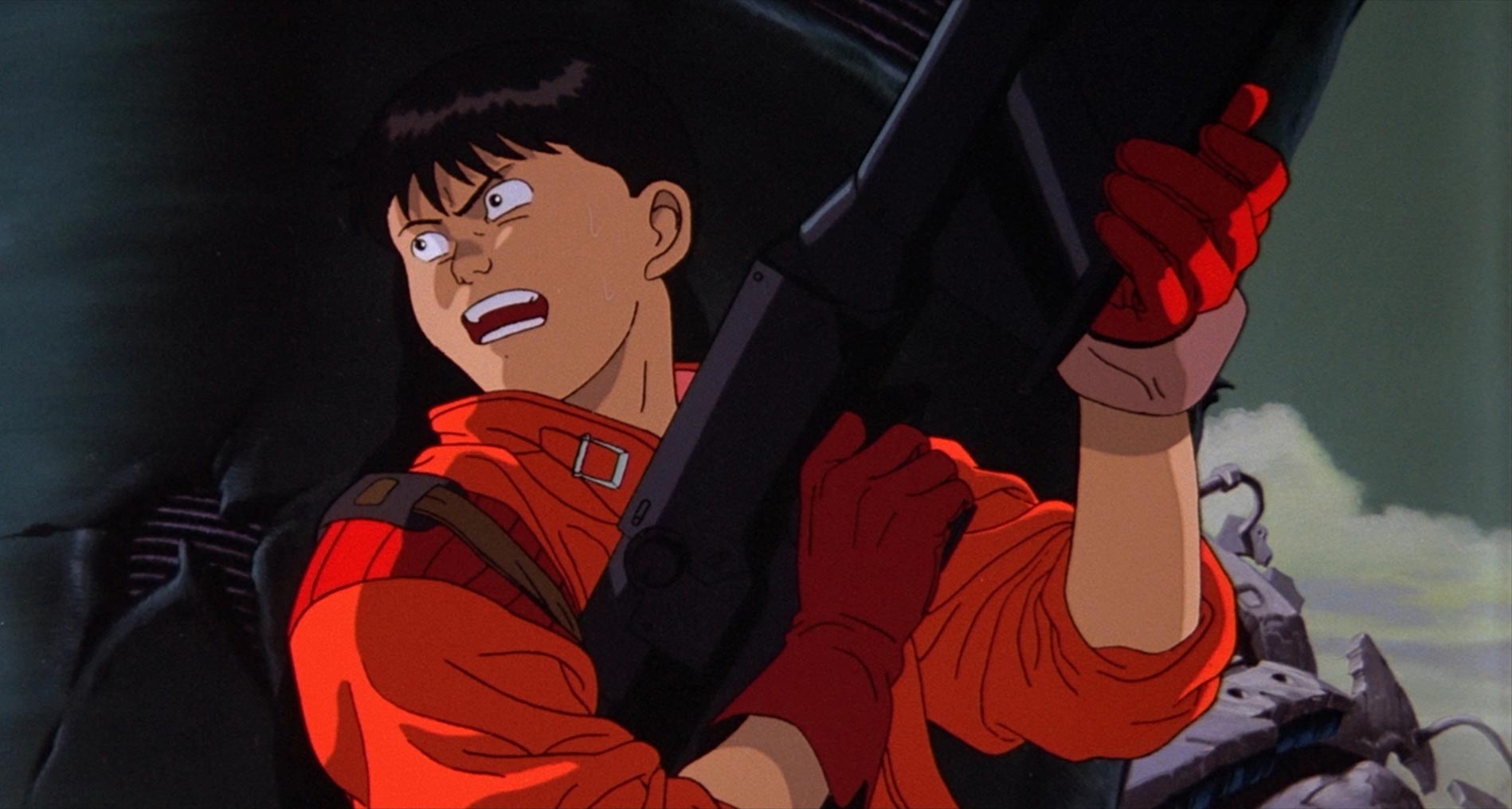

1. Akira (Katsuhiro Otomo, 1988)

The most apparent, enduring title of sci-fi animation (although in terms of mainstream recognition, WALL-E would no doubt dwarf it) remains the Western world’s first major foray into Japanese animated films, and anime in general, making Akira one of the most pivotal recent gateways in the history of film culture.

How many movies truly have it all? For one interested in two of any of the following: sci-fi, animation, youth drama, amateur existential musings, pseudo philosophy, groovy gadgets and weapons, music of unclear genre or labelling, and hardcore violence, Akira is essentially the longest, most satisfying wet dream in mortal grasp (and if you thought that comparison was unnecessarily or excessively vulgar and crude, try this film’s closing twenty minutes on for size!).

We all know the story: We’ve heard it mocked a thousand times. Kaneda needs Tetsuo. Tetsuo needs Kaneda. The cinema’s favourite nation to inflict widespread havoc and explosive misery upon fulfils its long-standing role. The scientists and the soldiers go head to head, both sides of view are represented with eyes bulging, overdubbed English-Japanese accents piercing the TV speakers yelling their fears and viewpoints.

It is relatively easy to mock, but even easier to love, presuming your role as part of Akira’s gigantic sphere of appeal amongst the more niche of genres and male-oriented art/narrative brackets and traits.

Author Bio: Charles Barnes graduated highschool determined to leave the world of faux-intellectuals behind him, absorbing himself into an excessive gorging of cinema, determined to develop an individual, distinctive, voice in the world of film analysis and criticism. Working at a video shop, watching and writing about film in his spare time, the Australian teen is determined to put his name firmly in the history of Australian film criticism and theory.