“We live, as we dream—alone”

– Joseph Conrad

Although many see existentialism confined to the literary world, in reality it creeps into the dark latitudes of the cinematic sphere. Horror as a genre and existentialism as a philosophy actually share something in common. Both attempt to elicit a negative emotional response: what Jean Paul-Sartre described as “nausea”.

But what exactly is existential horror? It’s important to distinguish between anxieties which might be called visceral and those which might be called existential. For example, most animals fear death – that’s a survival instinct – but humans on the other hand can comprehend its inevitability. Death is a primal fear; fear that death is certain is existential.

Existential horror can therefore be defined as the dread and terror experienced by the individual upon realising the circumstances of their existence. In horror movies this translates to fears of isolation, uncertainty, meaninglessness, insignificance, oblivion, responsibility and inevitability.

In response to the above quote from Joseph Conrad’s ‘Heart of Darkness’, horror movies, perhaps more than novels, pose an opportunity to “live” and to “dream”. If film can be described as a dream, then a horror movie can be described as a nightmare.

It’s a lonely and unnerving venture, true, but it’s important that we face those deep, deep fears which have rattled every human being since the primal sludge gave rise to higher intelligence. We may finally connect. If a movie digs deep, scratches the bone and plucks a nerve, it might just mean you’re human.

1. The Birds (1963)

Often considered Alfred Hitchcock’s last flawless film, ‘The Birds’ stands a masterpiece of existential horror. Unlike in his earlier films, the villain of ‘The Birds’ is not human; the threat is everywhere yet nowhere, malevolent yet incomprehensible.

The film follows a young socialite Melanie (Tippi Hedren) who pursues a stranger (Rod Taylor) to his hometown of Bodega Bay; a small village which comes under the violent attack of birds of all breeds.

The enemy of ‘The Birds’ therefore is no single creature. The most terrifying scenes, namely of Melanie trapped in a phone box and then in the attic, flicker chaotically in all directions. . Her hands swing aimlessly at the creatures; the assailants are everywhere.

The calm suburbia in which we are fated to live is fractured; only anarchy remains. But why do the birds attack? Probably the most enduring aspect of ‘The Birds’ is that it leaves its central mystery unresolved. Unlike ‘Psycho’, where Norman Bates’s multiple personalities is extensively explained by a psychologist at the end of the film, ‘The Birds’ gives no hint of a motive. The world is inexplicably on the edge of chaos and then the movie just ends. There’s no comprehending, no overcoming.

The monsters aren’t mythical; they’re harmless birds that we see every day. And who knows how a bird thinks? It’s terrifying because it suggests that ultimately we’re incapable of understanding the forces which aim to destroy us every waking moment; we can merely succumb.

2. Rosemary’s Baby (1968)

Roman Polanski’s adaption of Ira Levin’s novel remains one of the greatest ever horror films. It stubbornly lingers under the skin, striking those most elemental fears: we know nothing of those closest to us; in their eyes we’re merely objects to be utilised.

Rosemary (Mia Farrow) moves into a New York apartment with her actor-cum-husband Guy (John Cassavetes) neighboured by a quirky elderly couple. There she falls pregnant and descends into terror and mistrust as she attempts to protect her unborn son.

Unlike earlier horror films, whose monsters could be encountered only if one was foolish enough to venture away from society, ‘Rosemary’s Baby’ take place slap-bang in the middle of a megacity. In fact, the film’s opening, which pans over a New York gothic flat accompanied by a delightfully creepy lullaby sung by Farrow, establishes a cityscape cloaked in shadow. Nowhere is safe; not our home, not our family, and not even our own body.

The film’s most disturbing angle however is its degradation of marital sacrament. In the final act, the paranoia reaches a crescendo and Polanski forces us to either dismiss Rosemary’s fears as that of a hysterical woman or, despite all reasonable excuses, believe in witches. It’s a test of faith that ultimately falls in Rosemary’s favour.

It’s the realisation that we’re merely objects whose sole purpose is to reproduce. In Rosemary’s case, whose womb is hijacked by a satanic patriarchy, any trust or individual freedom has been eliminated.

‘Rosemary’s Baby’ remains one of the most unsettling films ever made. It reminds that every aspect of our lives is corruptible; no possession, no place, no partner may be trusted.

3. Don’t Look Now (1973)

Nicholas Roeg’s appropriation of the Daphne du Maurier short story is one of the great British horror films. Devastating and complex, it exposes a vast and inescapable network of grief and pain which binds every moment; every tragedy.

Following the death of their raincoat-clad daughter, husband and wife John (Donald Sutherland) and Laura (Julie Christie) retreat to Venice in an attempt to recover their crumbling marriage. There they are told by a blind psychic that their deceased daughter is attempting to warn them of forthcoming doom.

‘Don’t Look Now’ explores the intricacy of fate and the tragic consequences for the individual who fails to defy it. As in other Roeg films, time splinters; the editing throws together similar images from different narrative points in the film. The sniggering face that emerges from the hood in the climax is shattering; the visions finally collide coherently and we appreciate there’s nothing to be done. It was inevitable.

Equally important is Roeg’s depiction of existential grief. His excellent direction and the performances of Sutherland and Christie as the grief-struck couple offer a driving force behind the film’s visual motifs. It beggars the question: is there any point to the tragedy? As the non-linear structure suggests, any instant is only comprehensible in conjunction with another.

The interconnectedness of ‘Don’t Look Now’ reduces an entire life, in all its pain and beauty, to a single moment. It’s chilling because it suggests that we have no control; we’re merely pawns on a chessboard.

4. Eraserhead (1977)

Even for a film by David Lynch, ‘Eraserhead’ stands out as one of the strangest and most unsettling movies ever made. It’s genuinely nightmarish; every monochrome frame bursts with existential fear of responsibility, meaninglessness, and oblivion, and a hope for transcendence.

It’s near-impossible to reduce the film to a synopsis; Henry (Jack Nance), an inhabitant of a desolate industrialised world, struggles with the horrors of family life after his girlfriend (Charlotte Stewart) gives birth to his mutated child.

‘Eraserhead’ forces us to ask several questions, first and foremost: What on earth is it about? In response, the plot itself is undefinable and ultimately irrelevant. Whilst some sequences may be allegorical, it’s nearly impossible to explain the entire film by one literal narrative, say a couple who is forced together after an unwanted baby. Certain sequences such as where Harry’s head falls and is collected to make pencil erasers point to an explanation that remains just out of reach.

Sartre described a sense of “nausea” in realising that no grand structure defined a life and that any deed was therefore the individual’s responsibility. The child’s incessant screeches and repulsive form is disturbing; it recalls the horrifying responsibility that will burden an individual when they accept their actions, sexual or otherwise, as fully their own.

In a Godot-like dream; Harry’s head is pushed off to reveal the face of his son beside the Tree of Knowledge. Does it show how our children supplant us? Or maybe the absence of a divine overseer? Unnerving most of all is that we don’t know what’s going on.

In ‘Eraserhead’ existence has been drained of all colour; all meaning. Maybe the clue is in the soundscape. “In heaven everything is fine,” the girl in the radiator sings; but this isn’t heaven and it never will be.

5. Long Weekend (1978)

Colin Eggleston’s underseen natural horror is one of the best films of ‘ozploitation’ cinema. More chilling and restrained than most other nature-gone-wild movies, ‘Long Weekend’ suggests that if we attempt to break the laws of our existence we’ll be punished; the universe will hammer us down and destroy us.

Peter (John Hargreaves) and Marcia (Briony Behets) attempt to recover their collapsing marriage with a camping trip in the Australian bush. After a series of disrespectful encounters, they come under the attack of the bush itself.

The monster is more than a single creature or species. Like other films of the Australian New Wave, ‘Long Weekend’ positions the bush as a living force which will consume the Europeans who trespass upon it. The enigmatic opening shot, noting a small crab crawling across a desolate rock before panning to the tumbling waves, forewarns of the insignificance of man in a hostile world.

‘Long Weekend’ diverges from the typical natural horror movie in that the enemy is seemingly everywhere without ever being seen. There is a suggestion of death: an empty campsite with a drowned van, a car trapped in spiders’ webs, an otherworldly synthesised score; but any monster remains off-screen.

Perhaps the creepiest encounter is with a dead dugong – the bunyip – which approaches their campsite without ever being seen moving. There’s dread too in watching the couple’s relationship slowly deteriorate; they are both alone in a world that is trying to destroy them.

Despite its obscurity, ‘Long Weekend’ is one of the eeriest films ever made. The warning is not to forget one’s place in the universe; break the rules and try to conquer, and the Earth will swallow you up.

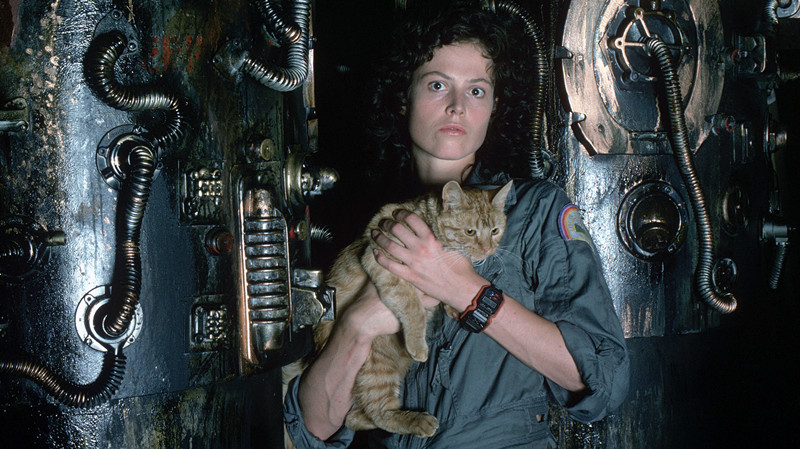

6. Alien (1979)

Ridley Scott’s creature feature has become an icon of popular culture. Offering a lonelier and more frightening view of space than what George Lucas offered in ‘Star Wars’, it has endured as one of the scariest films ever made.

The crew of the Nostromo follow a distress call where they unwittingly pick up and fall victim to a hostile extra-terrestrial lifeform.

Space itself is a threat. It’s black and silent; a lonely vacuum devoid of adventure. The planet which they visit, LV-426, has an almost gothic atmosphere. The colour scheme is bleak and characterised by stark contrasts between ominous shadow and ghostly mist.

Security seems can be found in the well-lit rooms of the Nostromo; but ultimately it’s the spacecraft’s isolation which turns the film into a claustrophobic nightmare. It’s the terrifying realisation of the universe’s indifference; in space no one can hear you scream.

Something too deserves to be said of H.R. Giger’s design of the alien. It’s horrifying on several levels; it’s quasi-sexual, parasitic lifecycle plays on fears of violation and the reduction of body to reproduction. Creepier still is that the alien is humanoid; it is an unknown monster which still bears similarity to us. It cannot be reasoned with yet knows only one thing: survival.

‘Alien’ taps into our deepest fears. It offers an answer to the persistent question of whether we’re alone in the universe. Even though the answer is no, our species never felt more isolated.

7. The Thing (1982)

John Carpenter’s faithful adaption of ‘Who Goes There?’ is arguably the best science-fiction horror movie ever made. Featuring spectacular visual effects by Rob Bottin (and also Stan Winston), ‘The Thing’ stands as a disturbing exercise in existential horror.

A remote Antarctic outpost becomes infected by an extra-terrestrial organism which can multiply and assimilate any organic material.

‘The Thing’ evokes fear in one’s own essence. It raises several philosophical questions regarding the self; namely if you were an identical replicate of yourself created by the alien, would you know? How could you prove you were the ‘real’ you? The movie takes familiar forms and then distorts them freakishly: a decapitated head grows spider’s legs and a dog grows Lovecraftian tentacles. Body and soul is corrupted. Humanity has been reduced to what it simply is: self-replicating biological material.

‘The Thing’ takes place in a space which is secluded. There’s isolation to be found not only in the infinite Antarctic wilderness but also in the alienation of the characters; paranoia spreads through the company as virulently as the disease itself. Who may be trusted? The final scene fails to answer that question, as MacReady and Childs sit opposite each other only to realise it’s impossible to tell who’s human. Who’s corrupted? Neither or both?

The vague title of ‘The Thing’ perfectly forewarns the existential horror it will offer. Humanity has been reduced simply to a “thing” which can neither protect itself nor know itself.