While we don’t think about it often when it comes to modern film, choices in a director’s style or in a script fall into two different categories.

The first is ideas and decisions made for a modern thinker, people who want to relate to your characters, feel invested into your stories, or want to impress themselves with newer special effects and concepts. The other category is the type of cinema that doesn’t necessarily have to dismiss current viewers, but more so look toward a hypothetical future, and impress those who will eventually see these choices years after its creation.

Both have their strengths and weaknesses, and films of ranging qualities have come from both. Just because a film impresses in the past doesn’t necessarily mean it has to be dated now, and simply because a film is meant to withstand a changing film landscape, doesn’t mean present audiences can’t appreciate its bold attempts.

This list will be celebrating those forward thinkers, who don’t always succeed in entertaining either present or future audiences, but have had numerous examples of filmmakers and films that feel like they’d belong in the same theaters playing more modern favorites.

Some were misunderstood at the time of their film’s release, some were praised even back then. But they have all earned praise from modern critics and audiences, and they deserve recognition for being the old films that feel familiar to new viewers, regardless of age.

10. Peeping Tom (Michael Powell, 1960)

Peeping Tom was a later film in the career of Michael Powell, the successful British director. You may remember Powell most fondly as one half of the Archers, two filmmakers (The other being Emeric Pressburger) who, after small amounts of success individually, began working together. Originally, the team-up consisted of Powell directing and Pressburger writing, but starting with One of Our Aircraft Is Missing in 1942, they became co-directors.

This team-up lasted over a decade, and through a lot of fantastic early color films, including The Life and Death of Colonel Blimp, A Canterbury Tale, I Know Where I’m Going, A Matter of Life and Death, the especially gorgeous Black Narcissus, and perhaps most famously, The Red Shoes. The partnership ended in 1957, due to a noticeable decline in success. They decided they would experiment independently, despite some collaborations later in their careers.

Following the separation of two greats, Powell had earned minor success with a 1959 film entitled Honeymoon, before making and releasing Peeping Tom. You’ll find when fellow film fans credit something as being “ahead of its time”, it is often because the film begins to make more sense and earn more respect after a generation or two has passed.

But Peeping Tom encapsulates the phrase better than most, as it was extremely controversial upon release, and the amount of disgust created by the film practically ruined Powell’s directorial career. Finland banned it until 1981, and the critical backlash included journalist Leonard Mosley referring to the film as “nauseating and depressing”.

The film began receiving a critical reappraisal a decade or so following its initial release, and it’s not hard to see why. First of all, it’s absolutely stunning in its visuals. Powell returns to the creative colors and lighting that made him and Pressburger famous in the 40’s and 50’s, but with a much more dark story involving murder for the sake of watch (and rewatching) the faces of terror from the victims.

And speaking of the dark story, this was the main source of controversy, but nowadays the horrors that the film displays are more admirable than disgusting. Powell clearly had great ways to unnerve the viewer, but audiences in 1960 just weren’t ready for this level of disturbance and edge. But the 1960’s were a huge decade for changing the landscape of censorship in film, starting with films like Peeping Tom in 1960, and finally resulting in the abandonment of the Hays Code in 1968.

At a time where violence was often out of frame or ignored, and having a villain as a main character was risky for a mainstream filmmaker, Peeping Tom was passed over for being too strange and too intense for audiences at the time. But despite its oddities, it fits much better in a modern state of mind.

9. 12 Angry Men (Sidney Lumet, 1957)

Similarly to Josef Von Sternberg with The Salvation Hunters beforehand, and John Cassavetes with Shadows afterwards, 12 Angry Men was Lumet’s contribution towards the oncoming trend of low production films from new directors. Like Sternberg and Cassavetes, this was Lumet’s first major motion picture, and the budget for the film was largely spent on the twelve main actors. This shows in the film, as for the entire 96 minute runtime, only 3% of the film is spent outside the jury room.

The film itself is actually pretty simplistic, twelve jurors discuss a murder trial, in which eleven of the twelve jurors feel the man in the case is guilty, and the sole juror who disagrees with them does his best to prove the accused man’s innocence. However, Lumet uses a captivating script and some fantastic actors to his full advantage, and made a very intense and thought-provoking film.

Critical reception at the time was actually very positive, and it received three Oscar nominations, but it was a bomb at the box office, mostly because of its restricted setting, as well as being made in a time where color films were much more popular than black and white films, and a black and white political drama in 1957 was not a big seller for theaters. (Unless it was by Billy Wilder)

The film earned its attention after its theatrical premiere thanks to its showings on television, and a very passionate cult following ensued.

Now that the film is being delivered to those who don’t mind black and white, it has become a much bigger name than what was originally expected, and it’s now regarded as one of the best films of the decade.

8. Fantasia (Norm Ferguson and Company, 1940)

Disney is an interesting case for a list like this, because a lot of their earlier work holds up wonderfully today. Incredibly charming early animated films, beginning in 1939 with Snow White and the Seven Dwarves, and continuing a now iconic line-up for a couple of decades. But Fantasia is an interesting case, as when it comes to what animated Disney films DON’T hold up after all of these years, it always comes to their compilation films.

Saludos Amigos, Make Mine Music, Fun and Fancy Free, Melody Time, these films all took the style of compiling several good short films into a pointless feature film. These short films were always ordered strangely, and the transitions between short films were non-existent, or just awful (Fun and Fancy Free is by far the worst offender).

Yet one of the greatest Disney films ever made happens to be one of these compilation films. That film is Fantasia, which is still regarded as an animated masterpiece. The biggest reason for this was just how spectacular the short films were. Save for Dance of the Hours, which came off as just silly, these short films matched the orchestral music perfectly, and the animation is some of Disney’s greatest. Toccata and Fugue in D Minor and Night on Bald Mountain may be Disney’s greatest creations, though that’s obviously debatable.

Another reason why this film holds up much more than its contemporaries was that there were breaks in between the short films to allow the viewer to breathe, and they actually had a narrator introduce each segment, describing the musical piece and how the animation matches the tone. It’s informative, easy to understand, and wickedly entertaining.

There’s even a small break where a single white line changes when a different instrument plays, as the narrator describes the context. The filmmakers clearly knew just a long series of short films would grow exhausting, so these little breaks are refreshing.

Enough with comparing it with other films of the time, why does it hold up by itself? Well, as already stated, the animation is wonderful, but the musical pieces chosen are perfect too. Any of these sound great on their own, but they’re even better paired with the animation. (Again, save for Dance of the Hours, where the music stands better by itself)

Finally, order plays a big role is how to place the segments in the overall feature. The problem with later Disney compilations is they didn’t seem to know where to put each film, and rarely does a film’s placement as a whole feel satisfying. But Fantasia is perfectly laid out, it slowly shows you what the animation can do with its first two shorts, the next few seem to experiment with the animation in different scenarios, and finally, Night on Bald Mountain gives the biggest rush of intensity, and it serves as a great climax for the full film.

The difference between Fantasia and its contemporaries is jarring when you see how they were treated by comparison. Fantasia is often shown in full, excluding the times where The Sorcerer’s Apprentice is used as a part of Fantasia 2000. The other compilation films of that era are almost always split up into individual short films, and even then, a lot of them don’t hold up in the same way that Fantasia does.

7. Le Bonheur (Agnes Varda, 1965)

One of the most brilliant films ever made, just happens to be one of the more underrated. Which is strange, as this seems like a film that would earn a cult following in recent years. Perhaps it has been overshadowed by Cleo from 5 to 7, another fantastic film by the same director, but nevertheless, despite its small audience, it certainly fits the criteria for this list.

It’s hard to discuss this film without spoiling everything that makes this film fantastic, but the bare minimum is that there is a man, a woman, and two children, and they have a perfectly happy life. In fact, it’s overwhelmingly happy. The film actually was given a new color negative after the original faded, so the colors are way stronger than normally seen in movies back in 1965, or even now. The film’s title literally translates to “Happiness”, so there’s no doubt about the initial mood of the film.

Make no mistake, however, this film doesn’t spell anything out for you. As a quick hint before watching, it’s not too confusing, but it takes a long time to digest. Nothing is spelled out, but like more modern films like Mulholland Drive, every little revelation in the viewer is like a personal achievement. Though Le Bonheur is much less vague than Mulholland Drive, as once you discover its trend, everything else falls into place.

The French New Wave was huge in discovering a style of filmmaking which would influence more modern styles, and while Le Bonheur isn’t one of the more popular examples of a French New Wave film, it hasn’t aged a day.

6. A Man Escaped (Robert Bresson, 1956)

If there is any filmmaker I can say completely refused to conform to anyone’s standards or styles, it’d be Robert Bresson. For one, he is one of the few directors who’d have his actors underact for the sake of audience immersion, which critics always loved, but audiences seemed split on.

He also let the entire French New Wave happen around him, without ever feeling like he borrowed even a single inspiration from it. He took a short while to develop his niche, but once he did, he never tried to be someone he wasn’t. Depending on who you are, you could say that’s a sign of a shallow filmmaker, or a brilliant one.

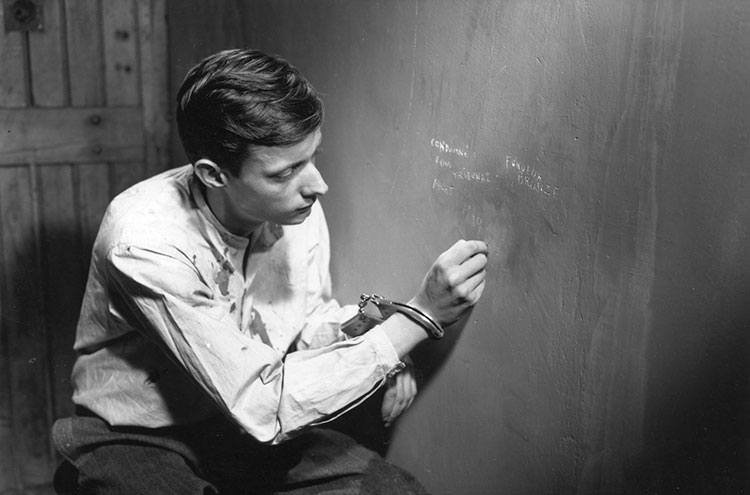

A Man Escaped is an earlier film from Bresson, and it may be his most accessible. Some may argue the deliberate underacting diminishes Pickpocket or Au Hasard Balthazar, as again, it was a controversial choice by Bresson to have his audience project their emotions on the characters.

But A Man Escaped is possibly the most appropriate use of this idea, as in a prison environment, especially when planning a prison escape, emotions are repressed by prisoners, and the overall mood of most prison films are of frustration and boredom. Both of these work well with Bresson’s style, so even if you’re aware of Bresson’s use of underacting in his films, it makes perfect sense in this film.

So while modern audiences can be turned off from Bresson’s more emotional work (Such as Au Hasard Balthazar, arguably his best film), A Man Escaped is a lot easier for modern audiences to digest, and its comparisons to other popular prison films like Shawshank Redemption don’t hurt either.