If horror cinema came to fruition and experimented with all manner of wonders in the silent film era, sound didn’t so much kill it as streamline it for effect. Certain norms came into play that kept film-makers from imagining themselves all the way down the wrong blind alleys (as silent filmmakers occasionally did) and had them focus instead on a purer distillation of crackerjack frights.

At the same time, if a certain perturbed and radical audio-visual sense, the ability to create worlds unlike our own, was lost for a little while, there remained plenty of breathing room for subtextual exploration.

Likewise, few born and bred on the violent reds of blood and the garish yellows of rotting flesh may know the joys of chiaroscuro cinematography, but nothing captures soul-struck chill and spine-tingling death with the same eye for clarity and, in rare cases, gloriously disquieted beauty.

Black-and-white sound horror more closely approximates our modern world, but it still has a power to unnerve and lash out at us – and to explore the deeper, darker parts of our hearts and minds. When they work best, as with these twenty films, they take us with them and make us wish we hadn’t come along for the ride. Please note we didn’t include any black & white silent films here because we have already made a list of it.

20. Freaks (1932)

Tod Browning’s 1932 feature is a curious and difficult beast, largely because it is, for most of it’s running time, not even remotely concerned with the genre we might suspect it to be indebted to. The story of deformed circus performers, it’s more working class tragedy and a study of other-ness than anything else.

Browning, who grew up in the circus, is largely sympathetic to the titular characters, ing them as social outcasts bonded by family and the need to survive one more day in a society that doesn’t want them. Throughout, he characterizes them less through back-story than through subtle, workaday details that allow us to fill in their personalities with impressions rather than mandates.

Eventually, the narrative gains momentum as society sicks itself on the freaks and they are left with no choice but to fight back. The film identifiably tethers us to their perspective as it courts audience sympathy for them. Yet, when the film does inevitably dovetail into horror, things take a turn for the better and the worse.

On one hand, the late-film sequence where the freaks do gather and take arms is easily one of the scariest things ever filmed, as Browning dials up the hazy sense of decay and the stop-start motion that approximates something deeply in-human. Yet, for this reason, the film also sacrifices its warmth and radical sense of sympathy for the others Browning knew so dearly.

In its place, it works filmic wonders, but to questionable means, with a final scene that sees sweet revenge upon those who would do them wrong, but which undeniably plays up the creepy otherness of the characters the film had until that point looked on with deep humanity.

19. Village of the Damned (1960)

1960’s stately British horror Village of the Damned doesn’t hold a candle to a number of other truly mesmerizing black-and-white horrors released that same year ( several of which appear on this list), but its restrained and clinical atmosphere elevate a film that follows in the Lewton spirit of implying and evoking rather than demanding or dreading.

Most of the film’s mileage derives from the presentation of its conniving, confused, menacing children, all of whom are given wigs with extra padding underneath (giving them bulbous heads) and piercing eyes to capture an uneasy sameness. More amusingly, they boast a sort of flat, monotone arch-British collective curiosity of a voice that haunts as it pokes fun at British stodginess and social mores which favor compliance and a self-righteously professional lack of emotion.

The film is also something of a parable of the quintessentially adult fear of youth, often unstated and left hanging in the air in a society that must only view children in a positive light, at least openly. Village of the Damned takes the unstated concern and runs with it, giving us a chiller that nervily worries about the fundamental essence of humanity: the young take over the old and rule the world.

To this extent, the film works better as a social examination of a small community coping with fear than a proper horror, with no small amount of ethical tension about how to remove an entity that is more notable for the threat of future evil rather than any current evil it has done to the world.

18. The Tingler (1959)

The Tingler opens with a perfect statement of intent – director William Castle introducing himself and essentially telling us to be prepared for a jolly good fright and nothing more. We see in his mannerisms an avuncular joy and giddy energy at the thought that we are not only about to view his film, but we are about to experience it. The film then proceeds to make good on this promise.

Of course, Castle is matched perfectly to his frequent screen collaborator, the smarmy, warped, eloquently slithering human-oil of Vincent Price, a man himself plagued by type-casting but who always seemed simply invigorated with every single line he ever read in each film he called home.

This story, about Price’s character grappling with some sort of new-found creature he calls The Tingler, is mostly just a means to an end. That end, however, is pure presentation entertainment of the most goofily endearing variety, a film that is so busy having a boatload of fun playing around with filmic tools its too busy to notice it isn’t really meaningfully scary.

In addition to the multitudinous over-acting, we have a very early filmic drug trip accompanied by all manner of loony images, one sequence filmed in color but with a set and actors essentially painted gray (so that the blood uneasily pops with an almost pop-art level of kitschy color), and, of course, the finale where the Tingler is let loose in a theater and the characters approach the fourth wall by telling the audience to scream to prevent the Tingler from killing them.

Of course, they’re really talking to us, and Castle isn’t much interested in hiding this fact- he’s here at our service, and he wants us to know it. All of it adds up to a depraved delight the likes of which only William Castle could produce (audiences should also check out the similarly loopy House on Haunted Hill, Castle’s most famous depraved delight).

17. Carnival of Souls (1962)

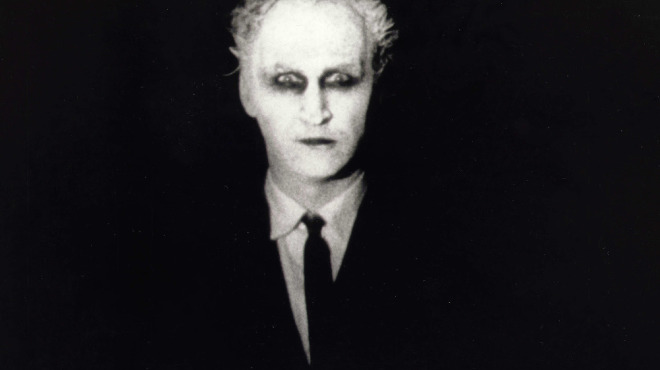

Carnival of Souls truly should not work – it is a profound mess of a film, a collection of poorly scripted and uneasily acted scenes that plays more like a middle-school stage production than a proper film. Yet, it is precisely for this reason that the film gasps, gulps, and chokes its way through a non-narrative that approaches us like a figure from an alien world trying to feign humanity.

More than anything, the film’s narrative doubles as an examination of the impression of death and how one might dream of a leftover life while waiting for the soul to follow the body into the great unknown. The film’s implication that what one might imagine is based on cheap-as-can-be campy 60’s nonsense film-making and borderline Ed-Wood quality perversions of humanity is wonderfully endearing, but it more than anything speaks to the film’s early 60’s schlock credentials.

The product of mid-western commercial filmmakers who decided to have a little fun on the side, its likely they’d seen more than their fair share of early 60’s drive-in features and felt the ensuing dialectic: being repelled by their general tomfoolery yet inexplicably drawn to their sublime drugginess and soul-drudging nightmarishness.

And indeed, the film has a scrappy energy that is positively undeniable in spite of itself. In one scene, the film takes the cheap film-making technique of midnight cinema and goes for it with such a delirious level of aplomb – they give us four consecutive crash zooms on top of each other – its positively grin inducing.

The film elsewhere hammers on the most non-nuanced organ blasts one could possibly imagine, and then self-reflexively critiques itself by having the main character actually play the organ in the film (a rather dour and snarky joke at the expense of that particular soundtrack choice ubiquitous throughout the early 60’s).

When it gets explicitly nightmarish in the later scenes, we’re treated quite literally to a carnival of nightmare souls including early waterlogged ghouls that no doubt influenced George Romero. Meanwhile, Roger Ebert was right to point out the surrealist vision of small town America likely kept David Lynch up at night. The film, warts and all, is positively alive in its guerrilla deathlessness.

16. Dead of Night (1945)

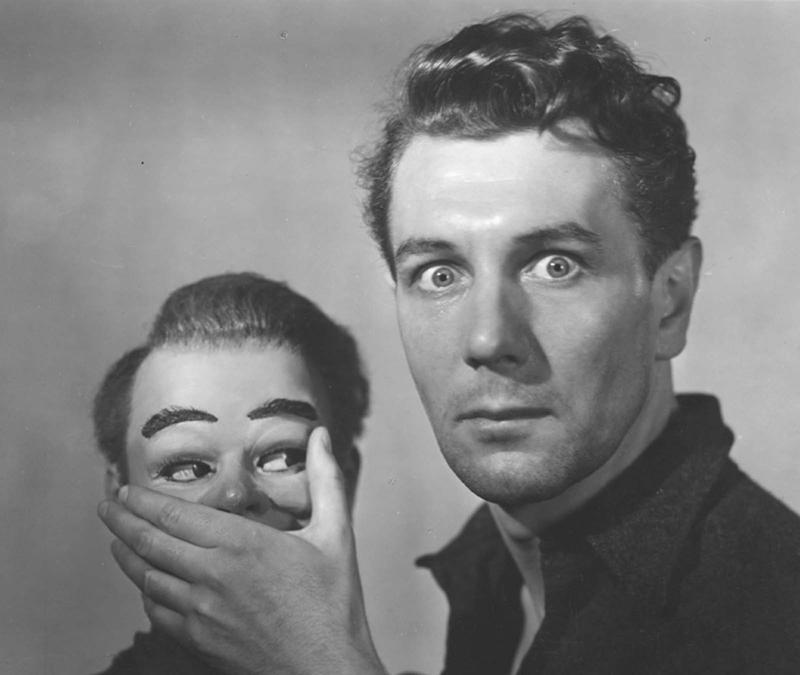

One of the first anthology films, Dead of Night marries a stately British manor story with plenty of chilly, deadened spooks, some particularly stunning shadow-work aimed at capturing primal fear and psychoanalytic tension, and a small helping of light, cheery comedy, for a total that exceeds the sum of its considerable parts. It’s undeniably playful, but only so much so that we fail to notice for most of its running length how deeply we’re chilled to the bone.

The most famous segment, the film’s most piercing banshee shriek into the night, is its final one, a terrifying examination of split personality, psychoanalytic ambiguity, and the raw, clockwork fear of dolls that ape a sort of malformed, caricatured, grotesque humanity.

In other words, it’s a ventriloquist’s dummy tale, here directed by Alberto Cavalcanti with a true eye for dreary imagery. But unlike later adaptations of the story, this one self-reflexively centers the crippling and brittle nature of theater and performance, and it maintains the core ambiguity of the story all the way until the end.

Incidentally, this film was a prime inspiration for The Twilight Zone, in its melodramatic, sometimes stagy dialogue, its emphasis on primal nightmares, its noirish camerawork, and its pointedly theatrical underpinnings. So if this film feels quite like a collection of episodes from the show, they’d be five of the best, and that’s all that matters.

Of course, it also has the finest wraparound narrative in any anthology horror film, and the film’s scariest bit occurs right at the end of this wraparound, when aspects of each story converge for a kaleidoscopic descent into pure hellish madness.

15. Hour of the Wolf (1968)

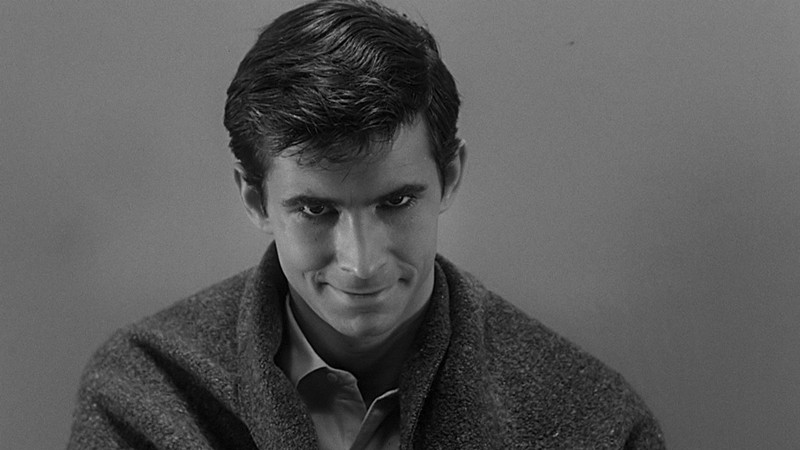

Ingmar Bergman’s 1968 psychological horror is one of his lesser known works, likely due to the commercially uneasy combination of art film sensibilities and horror imagery. Too queezy and diabolical for some and too clinical and cold for others, it is Bergman at his most menacing, but Bergman none the less.

Despite being Bergman’s “horror” film, it’s also quite conciously and clearly part of his larger corpus of non-horror works. Thematically, it’s arch-Bergman, with an artist (Max von Sydow) trapped in a viper’s nest of his own mind and given no recourse but his own thoughts to survive on. Most of the tortured filmmaker’s works dealt with internal self-mutilation and clinical madness, but Hour of the Wolf sees him at his most expressive filmically in dishing out the destructive parameters of the human mind.

Stylistically, the film also bears unmistakable Bergmanisms, but it’s a bit more expressionistic than his more famous works. The clinical, detached atmosphere is still front and center, but the black-and-white oblivion the film centers visually is too chaotic and damaged to be as sedate and calm as a typical Bergman film. He has a field-day with anxious imagery and elliptical thoughts rendered pentrating by the filmic gaze.

The only other major character in the film is Liv Ullman as the artist’s companion, the only figure who could save him from his own thoughts. Yet, in the film’s opening and closing, she speaks directly to the camera about the contagion of madness, going so far as to reflect on everything we witness in the film as a “story” of fiction, itself a work of madness. She’s been infected too; we come to question whether she could ever save him, and begin to think his thoughts made her victim as well.

The Bergman “horror” claim tends to undervalue how at-odds the film is from the horror genre – it’s not so much scary as it is haunting and eerie, a very quintessential Bergman film about Bergman’s favorite theme (this time with just a little more ravaged style than normal) and just as subversive and eternally new as any of his films. His substantive Bergman bite is the same as always, but this time the stylistic bark of horror leading up to it is a little bit louder and more piercing on its own.