The 1970s were a monumental decade for enthusiasts of cult cinema, marked by a departure from conventional studio norms that opened up avenues for filmmakers to delve into unconventional themes, styles, and narratives. This transformative era was heavily influenced by the countercultural movements of the 1960s, which paved the way for audiences to seek out alternative cinematic voices. In bustling urban theaters in the USA, Blaxploitation and Hong Kong kung fu films filled screens, while those in the suburbs stayed home, tuning in to bland television offerings.

The success of The Rocky Horror Picture Show (Jim Sharman, 1975) as a midnight movie at New York’s iconic Waverley Theater underscored the enduring appeal of communal film-watching experiences. This realization sparked renewed interest among exhibitors and audiences alike, reaffirming the demand for exhilarating cinematic journeys like Eraserhead (David Lynch, 1977) and The Holy Mountain (Alejandro Jodorowsky, 1973). These resonated with cult audiences, boasting the grand aspirations of art films while embracing the audacious imagery of horror and science fiction.

Across Europe, maverick directors like Jean Rollin and Jess Franco were prolific and uncompromising, pushing the boundaries of cinematic conventions and good taste. In Japan, pink films and hyperviolent Samurai dramas were the order of the day, while in Hong Kong, thanks to companies such as Shaw Brothers and Golden Harvest, kung fu stars such as Bruce Lee and Gordon Liu were coming to international prominence.

While cult favourites such as House (Nobuhiko Obayashi, 1977) and Suspiria (Dario Argento, 1977) have gained widespread recognition, there exists a treasure trove of lesser-known gems that deserve exploration. Here are ten cult 1970s films you may not have seen, taking in magic realism, revenge, and all the variety that the 70s had to offer.

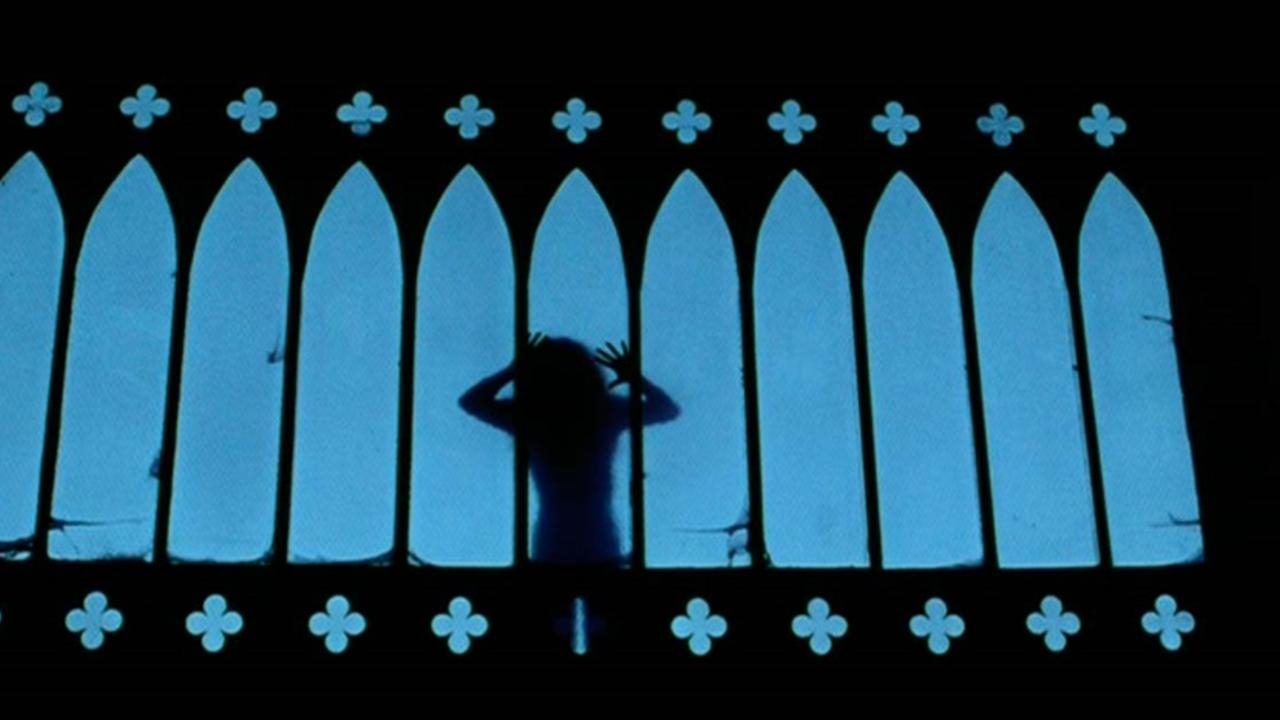

1. Valerie and Her Week of Wonders (Jaromil Jireš, 1970)

Perhaps the oddest and most psychedelic film on this list, Valerie and Her Week of Wonders is a surreal film from the tail end of the Czechoslovak new wave. The film is a mesmerizing and unnerving journey that blends fantasy and horror with overt coming-of-age elements, prefiguring the magic realist literature of Angela Carter. The film follows young Valerie as she navigates a bewitching week in a mysterious village, encountering vampires, witches, and other unpleasant embodiments of adulthood. Valerie has to navigate these characters, her own innocence, and explore her womanhood.

The film’s dreamlike visuals, an ethereal score filled with flutes and harpsichord by Luboš Fišer, and seamless transitions between reality and fantasy create an enchanting yet unsettling atmosphere. Perhaps having Ester Krumbachová serve not only as the writer (adapting a 1935 novel by Vítězslav Nezval) also work as the film’s production designer gave the film a particular sense of coherence despite its surrealism. Valerie and Her Week of Wonders was undoubtedly an influence on The Duke of Burgundy (Peter Strickland, 2014), which tries to channel its dreamlike eroticism. But whatever it subsequently influenced, there will never be another film with the same strange dreamlike atmosphere as Valerie and Her Week of Wonders.

2. Lady Snowblood (Toshiya Fujita, 1973)

Best known today as an influence on the two volumes of Quentin Tarantino’s Kill Bill, 1973’s Lady Snowblood deserves to be much more than a footnote to a contemporary American filmmaker’s work: it’s a stylish revenge thriller that portrays Yuki, a woman literally born to take revenge. She is a vengeance machine, determined to track down the band of criminals who raped her mother and killed both her parents. This is admittedly a grim, nihilistic tale, but one filled with striking visuals, vivid colours brought to life by cinematographer Masaki Tamura, and that visceral yet balletic approach to violence that is characteristic of 1970s Japanese films such as the Lone Wolf and Cub series.

Furthermore, Yuki’s blood-drenched quest to meticulously eliminate those responsible is told in a narrative that that skips nimbly from past to present, and is split into chapters, perhaps a hint to the story’s origin in manga. Director Toshiya Fujita, (who usually worked in youth films and risqué pink films) skilfully brings the narrative to a shocking, violent climax that takes place at a masquerade ball. There was a sequel the following year, Lady Snowblood: Love Song of Vengeance, but although it’s an interesting film, it does not have the sheer bloody impact of the original film.

3. The Spook Who Sat By The Door (Ivan Dixon, 1973)

Sometimes characterized as a Blaxploitation film, The Spook Who Sat By The Door is in fact a politically-charged and radical thriller. In the first film, we see Dan Freeman become the first black CIA agent, and watch as he completes his basic training and begins to rise through the ranks, despite antipathy from his white colleagues. He’s considered a spook in the double sense of a spy and a racial slur, and he “sits by the door” so that visitors can see him; a symbol of tokenistic diversity. As the audience begins to wonder where this procedural narrative is going, Freeman suddenly returns to Chicago, where he recruits a group of black militants and trains them with everything he learned at the CIA. Freeman’s aim? To overthrow the government and dismantle systemic racism.

The film’s soundtrack was composed and conducted by jazz legend Herbie Hancock, who made innovative use of the ARP 2600 synthesizer. Hancock’s compositions vary from the kind of music audiences would expect from a Blaxploitation film with more avant-garde sounds. On the downside, the film is stodgy and slow-paced at times (director Ivan Dixon is better known as one of the stars of the TV sitcom Hogan’s Heroes), but in its satirizing of affirmative action programs and the CIA, plus its deadly serious messages about blowback and revolution, this is a sometimes uneven but always uncompromising film.

4. Terminal Island (Stephanie Rothman, 1973)

Terminal Island, a 1973 exploitation film directed by Stephanie Rothman and made for cult cinema mogul Roger Corman, is a gritty and thought-provoking thriller set in a dystopian future. The film’s first and most successful section provides exposition on this dystopia, where crime has run rampant and prisons have become overcrowded – through the newsroom production of a TV news segment. This segment recalls the prescience of cult television film This is the Year of the Sex Olympics (Michael Elliot, 1968) and the later more mainstream treatment of similar televisual voyeurism in the film Network (Sidney Lumet, 1976).

After this attention-grabbing opening, the rest of the film then unfolds on the eponymous “Terminal Island”, a secluded island turned prison where violent criminals are left to fend for themselves. As the inmates struggle for survival, they must navigate an unforgiving natural landscape and a ruthless prison hierarchy. Carmen and Bobby, two newcomers, challenge the island’s brutal system while forging an unlikely bond. Rothman’s film delves into themes of power, justice, and human resilience, offering a captivating blend of brutal action and social commentary.

The film has a rough around the edges, low-budget charm. However, Terminal Island does continually use the threat of violence – and sexual violence in particular – against women in a way that is very in step with 1970s exploitation cinema, but in a way that Rothman herself ended up unhappy with. But like many exploitation films, it’s ambiguous: simultaneously filled with mindless violence and yet critical of the nascent prison-industrial complex.

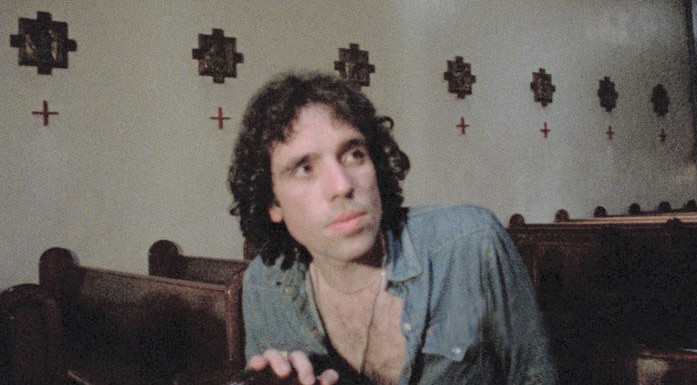

5. Messiah of Evil (Willard Huyck and Gloria Katz, 1974)

Messiah of Evil was written and directed by Willard Huyck and Gloria Katz, who are better known as uncredited writers on Star Wars Episode IV: A New Hope and for their other collaborations with George Lucas. Anyone expecting the breezy adventure of Star Wars and Indiana Jones would be sorely disappointed watching Messiah of Evil: it’s the bleakly atmospheric tale of Arletty, a lone woman in search of her father, who arrives in the eerie northern California town of Point Dume to visit her father and finds him missing, and pursues a mystery that involves mysterious cultists waiting on the beach at night, and a mystery that goes all the way back to the Doner Party.

It’s as if HP Lovecraft decided to wait out the cold New England winters in California: the mysterious correspondence left behind after a disappearance, desolate setting, and modern manifestation of an ancient evil all feel like a fresh twist on Lovecraftian tropes. But it’s also a film that portrays the “flower power” of the 1960s as degenerating into a kind of dazed, hungover drifting. While this is a film that stands out primarily due to its atmosphere and set pieces (such as the town’s blood-crazed residents attacking one of the drifters in a late-night supermarket), there’s also a great performance from Elisha Cook Jr as an eccentric old man, and even a cameo from cult director Walter Hill.

For critic Kim Newman, 1970s American horror was the era of “the American nightmare”, when independent creators were able to pair up with money-savvy producers and express themselves personally within the framework of the horror genre. It’s a pity the talented Huyck and Katz weren’t able to supply us with more such American nightmares.