Quentin Tarantino dubbed: “‘80s cinema, along with the ‘50s, the worst era in Hollywood history. In the ‘80s, it was self-censorship. It was the rise of political correctness after the ‘70s, where everything was just ‘go as far as you can. ’Then, all of a sudden, everything got watered down. Everything was cynical, then, in the ‘80s, all that was washed away. The most important thing about a character was that they were likeable. Every character had to be likeable.”

It would be too easy to merely characterise the 1980s as an era of yuppie greed and heartless commercialisation, typified by the depiction in Oliver Stone’s Wall Street. On the other hand, this reduction doesn’t tell the whole story of a multifaceted decade which was also vibrant in the arts. While the yuppies’ ruthlessly money-centric, bland, culturally regressive mentality was indeed a distinguishing feature of the time, it proved fruitless in extinguishing the expression and determination of great artists. Evident in E.T. and Back to the Future, the ‘80s in fact contained a prodigious wealth of sensational Hollywood movies, of equal quality to the releases of the ‘70s.

Although his characterisation of the industry’s climate at the time is accurate, what Tarantino has failed to identify is that creativity and proficient filmmaking are not dependent on temporality. The ‘80s saw the rise of many singular, unadulterated filmmakers, like Jim Jarmusch and David Lynch. What is more, in regard to crime movies, from The Long Good Friday to Scarface to Blood Simple, the ‘80s clearly professes its fair share of excellent titles. That said, many of the crime genre’s best pictures still haven’t been recognised for their calibre and were brushed under the carpet. This list aims to champion lesser-known or forgotten ‘80s crime movies in need of reappraisal.

1. Babylon (Franco Rosso, 1980)

Brinsley Forde, vocalist of the reggae band Aswad, plays the film’s protagonist: Blue. Blue lives in Brixton, London and is of Jamaican descent. The narrative follows him pursuing his ambition of becoming the toaster (rapper) of a dub sound system with his friends. Meanwhile, he must navigate the intense racism of Thatcher-era England, directed at him from police and civilians alike.

Babylon was co-written by Martin Stellman, who penned the similarly plotted Quadrophenia (1979) and went on to write Yardie (2018). One of Babylon’s strengths is how it portrays the richness of Jamaican culture: the heady atmosphere of the dancehalls, the music, the slang and the mysticism of Rastafarianism.

Very few films depict British Jamaicans and fewer still delve into the discrimination they were forced to endure in a country that was far from welcoming towards them. Although it’s a heart-wrenching, gripping coming-of-age drama with a stunning soundtrack, Babylon has since been maligned. This is perhaps because it was independently produced and didn’t receive a wide enough release.

2. The Hit (Stephen Frears, 1984)

London mobster Willie Parker (Terrence Stamp) gives up his criminal associates in court in exchange for pardon. A decade later, Willie’s spending a peaceful retirement in Spain. This is interrupted when he’s captured by hitmen Braddock (John Hurt) and Myron (Tim Roth), who work for his ex-boss. They’ve been instructed to drive Willie to Paris to be executed.

Principally, The Hit is a literary film steeped in deep meaning and philosophical intentions. It succeeds as a profound, ethereal meditation on death, distinguishing it as a resonant piece for a broad range of audience members. This is engendered through its luscious, poetic, perfectly framed photography of the Spanish landscape: the Quixotic windmills, the mythical desert plains, the romantic apartments of Madrid. On top of its significance, The Hit is also a perpetually entertaining, freewheeling gangster-road movie mashup with both funny and thought-provoking dialogue and shootouts.

What is more, it’s infused with a score of Eric Clapton’s rock and Paco de Lucia’s flamenco guitar stylings. It hosts an intimate character study: Willie’s offbeat detachment, Myron’s comic naïvety and Braddock’s silent aggression. This is not to mention a turn by Australian legend Bill Hunter (Muriel’s Wedding) as the nervy, lovesick Harry.

Every actor contributes their best work, with Stamp permitted to deliver a career-defining monologue and Tim Roth proving his acting chops for later casting in Pulp Fiction. With every component of the film being outstanding, especially the philosophical screenplay, The Hit is inarguably one of the best movies of the ‘80s, despite being a commercial failure. Wes Anderson ranked it as the 5th-best British film of all-time.

3. The Evil That Men Do (J. Lee Thompson, 1984)

Holland (Charles Bronson), a former CIA assassin, comes out of retirement to exact revenge for the murder of his friend. His target is ‘The Doctor’ (Joseph Maher) – hired by multiple governments to inflict barbaric torture upon political prisoners.

While most audiences associate Bronson’s signature silent avenger persona with his best-known work, Death Wish (1974), The Evil That Men Do is an overlooked yet notable chapter in his gritty, vendetta-geared career. Bronson establishes the formula for the action stars that would attempt to replicate him, like Nicolas Cage and Jason Statham. Regardless, Bronson’s iconoclasm as an action hero remains unsurpassed. He brought a powerful, enrapturing screen presence which director John Huston described as “a grenade with the pin pulled.”

Although the film’s plot is typical genre fare, it’s enlivened by Hitchcockian suspense and daring action sequences, pertinent in its car chase, with an ecstatic, satisfying climax. It also supplies audiences with the texture of Guatemala – the beauty of its scenery, culture and people. At the same time, the script raises awareness of the nefarious private affairs of the governments we blindly invest our trust in, the abuse of power that’s concealed from the public.

4. Witness (Peter Weir, 1985)

A young Amish boy called Samuel (Lukas Hass) witnesses the murder of a cop in Philadelphia. The investigating officer, John Book (Harrison Ford), accompanies the boy and his mother Rachel (Kelly McGillis) into hiding in Amish country, Pennsylvania. Screen legend Danny Glover co-stars, alongside Viggo Mortensen in his film debut.

Upon its release, Witness was nominated for a slew of Academy Awards and won in the Best Original Screenplay category. However, the film has since been chiefly forgotten by contemporary genre fans for being one of the best crime films of the ‘80s, containing one of Harrison Ford’s most accomplished, tender performances. Witness achieves an intimate portraiture of Amish culture: the barn raising, their use of the Swiss German language, the horse-drawn buggies, exploring both the beauty and restrictions of their way of life.

Similarly, Witness shows audiences the duality of the police force: a commitment to humanism and protection of the innocent versus the corruption, as well as a debate about violence at-large. Unlike more flippant genre works, Witness treats violence with realism and considers its traumatic significance. The simple narrative is as near to perfect as a thriller can reach, underpinned by an affecting love story. Roger Ebert described the movie as “masterful filmmaking.”

5. Mona Lisa (Neil Jordan, 1986)

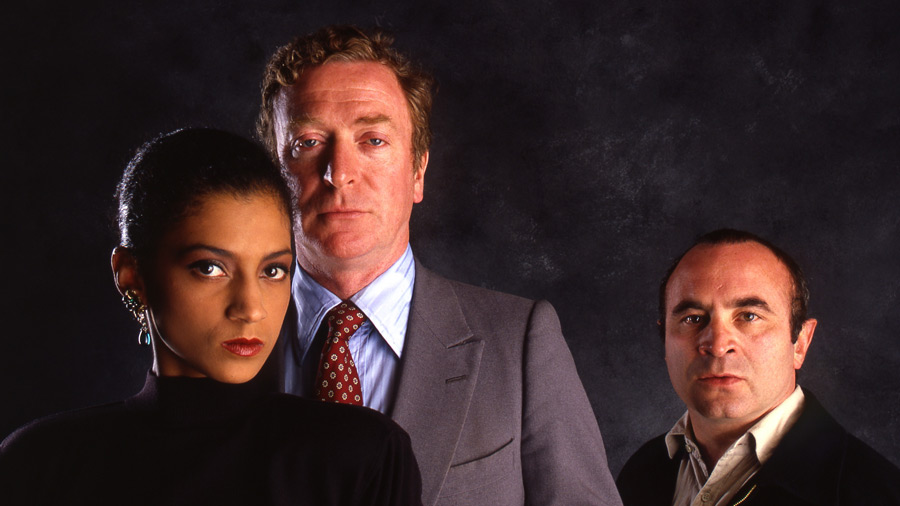

George (Bob Hoskins) is released after a 7-year stint in prison. His former boss, Denny Mortwell (Michael Caine), reemploys him to drive a prostitute named Simone (Cathy Tyson) to her clients. As they grow acquainted, Simone requests George locates her missing friend Cathy (Kate Hardie), but the mission proves to be fraught with danger. Harry Potter’s Robbie Coltrane is part of the supporting cast.

Firstly, Mona Lisa’s main attraction is the staggeringly masterful, passionate acting from the late Bob Hoskins, who brings a cracked vulnerability, complexity and humour to the character of George. Cathy Tyson’s multisided depiction matches his level and together, their comic repartee focalises the weighty, heartfelt narrative around friendship and surrogate parenthood. The exceptional script, drawing inspiration from Taxi Driver, is brought to fruition with forbidding, chiaroscuro-drenched lighting, sketching a vivid landscape of the seedy underground of London nightlife.

Moreover, as a feminist piece, Mona Lisa humanises the real people involved in the world of prostitution, bringing to light their mistreatment and exploitation. Produced by George Harrison’s company, Handmade Films (Withnail and I), the movie’s haunting climax in Brighton is all the more moving given the emotional investment Jordan attains through his intimate character studies, overshadowing formulaic thrillers. Mona Lisa allows us to get to know George and Simone like friends. It’s perplexing that it isn’t better-remembered and rated as a decade highlight. Both Hoskins and Tyson were clearly eligible for Academy Award nominations.