Chantal Akerman (1950-2015) emerged as a filmmaker of the American avantgarde in the 1970’s working in the structural school that saw Michael Snow’s 45-minute long zoom Wavelength and Andy Warhol’s 7-hour static shot of the Empire State Building making the rounds at art galleries and cinemas, but would go on to redefine herself in a career spanning genres and forms, breaking into both the arthouse and commercial mainstreams.

Born in Brussels, Belgium to Polish-Jewish immigrants and holocaust survivors, Akerman was religiously educated from a young age but would drop out of highschool at 16, shortly after seeing Jean-Luc Godard’s youthful and chaotic Pierrot le fou (1965) and being inspired to filmmaking with a desire “to make everything explode.” She would later attend a semester at INSAS, a Belgian film and drama school but would again drop out after just a semester opting instead to skip right to the directing with her first short Blow Up My Town in 1968. A nearly-silent comedy with echoes of Godard, the film sees a Chaplainesque Akerman manically preparing herself for suicide by gas-explosion. It found positive reception at the Oberhausen Film Festival in 1971, following which Akerman emigrated to New York City to pursue filmmaking in the heart of the American avantgarde.

Here she would discover the autofictional documentaries of Jons Mekas, the feminist works of Yvonne Rainer, and most importantly the structural films of Michael Snow, Andy Warhol, and Hollis Frampton, which presented a new and rigorous interrogation of film’s fundamental properties of space, time, and motion, and would in their experiments with duration introduce Akerman to a new relationship to film-time that would predominate the rest of her career. Akerman found a desire to create films whose meditations could demand active participation of their audiences, and create an experience of their runtimes rather than, as she saw conventional films doing, only take away two hours of the audiences’ lives. Akerman began her NYC career with the 1972 short La Chambre, a classically structural experiment in pure form as one unbroken take of three full rotations and five half rotations of the camera through an apartment space, the variable distance between object and camera creating a frame that oscillates abstraction and figuration.

As the 70’s continued she would direct two staples of the structural film in Hotel Monterey (1972) and News from Home (1976), but also find her own voice and stride in narrative films that integrated the technique and temporality of her structural films into works of fiction – most famously with 1976’s Jeanne Dielman – often the portraits of alienated women and semi-fictional travelogues, or panoramic explorations of a given space, with themes of identity, isolation, dislocation, and travel, all while drawing on sources personal and autobiographical to color these largely detached narratives with context and personality. Through these films Akerman would maintain a commitment to the quiet and the quotidian ordinarily deemed uncinematic in rejecting a mainstream “hierarchy of images” she saw as predictably fixed to the escapist dramas of action and romance while passing over the majority content of real life. Here too Akerman would develop her visual aesthetic of wide, single point perspective, and eye-level compositions square to the geometries of space, creating a look of painterly tableau even as her naturalist direction and observational style fostered a sense of hyper-realism.

Into the 1980’s and beyond Akerman would branch out from this experimental mode she had defined herself, and begin working more broadly and in more mainstream and commercial modes, like the socio-political documentary, artist profile and performance film, commercial drama, musical, and comedy, including a trip to Hollywood for the romcom A Couch in New York, while still making occasion to work the experimental modes of her defining period.

Totalling some 30 feature length films, more than a dozen shorts, and several installation pieces in the course of her career, Akerman’s work would influence a next generation of filmmakers including Gus Van Sant, Kelly Reichardt (who claims to rewatch Jeanne Dielman at the outset of any new project), Richard Linklater, and Apichatpong Weerasethakul, and continues, since her death in 2015, to be discovered and rediscovered as one of the great experimenters of narrative cinema.

1. Jeanne Dielman, 23, Quai du Commerce 1080 Bruxelles (1975)

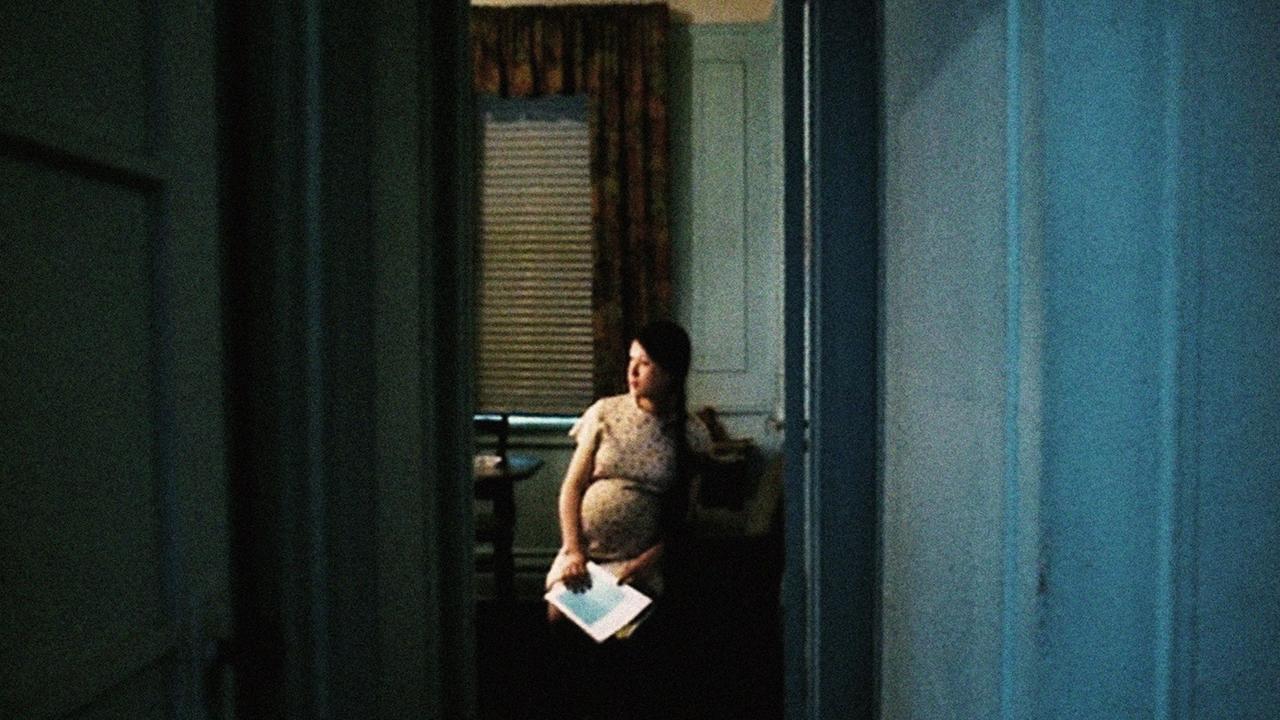

Arguably Akerman’s greatest achievement, and rightly the one that propelled her to international acclaim, Jeanne Dielman provoked and challenged audiences in 1975 breaking conventions of narrative cinema with its 3½ hour close-up on the fictional life of the widowed mother and prostitute Jeanne Dielman (Delphine Seyrig), grounded not in the sensationalism of her occupation or personal tragedy but the strictures of daily routines, cooking, cleaning, shopping, sorting, and taking care of her son (Jan Decorte), – including a famously boring potato peeling scene – and joylessly seeing clients while he is out of the house, all shown in long as if real-time documentary takes and elaborate even excruciating detail, the automatism of it all swinging between zenlike self-mastery and obsessive-compulsion.

Observing with this “phenomenological closeness” as Akerman calls it, the viewer finds themselves immersed willingly or not in the minutiae of Jeanne’s routine – the precise layout of the apartment and its rooms, the various surfaces in it and the order of repeated shots sticking to a predictable timetable – so that beneath a surface of boredom one no longer pays attention to, something troubling and strange seems to be building, and when an inconsequential mishap introduces a disorder that threatens to completely unravel the perfect system by which Jeanne conducts her life, a note of unexpected drama is introduced, leading Jeanne to a sudden and unexpected act of what may be self-destruction and may be liberation.

Lauded as a feminist film for its critique of a constrictive gender role that not only diagnoses Jeanne lost in her housewifely duties and left after the death of her husband to seemingly no choice but prostitution as well as staging some form of escape from her subjection to men, Akerman has also called it, paradoxically, a “love film” to her mother, and a form of recognition to “that kind of woman”, and admitting an internal uncertainty to just what she was trying to say. Probably the film is both of these things, and at any rate, neither is expressed overtly in the film, (Akerman decidedly not in the realm of Godard anymore) and up through its ambiguous ending the film presents a character altogether unforthcoming, and lets whatever drama there may be form beneath the iceberg, in the viewer’s mind.

2. Hotel Monterey (1972)

With Hotel Monterey Akerman found a culmination of her early interest in structural film in its exploration of the titular NYC hotel, a cheap and rundown refuge between 96th and Broadway that holds a strange beauty in the even-then historic architecture seen from the lobby, and the murky, anonymous, somewhat unreal, and slightly unsettling atmosphere of the empty halls by night.

The film consists of a silent, largely figureless, and systematic if incomplete examination of the hotel in 38 shots, from floor to floor, and hall to hall over the course of 15 hours, from sun down to sun up, starting from the lobby and working upwards, observing the bustle of evening check ins, the guests all filing into elevators and taking to their rooms, and clearing the halls for night, where the camera alone stalks moving slowly toward the rooftop and NYC skyline, in open air and early morning light. It is a study of the greens and yellows and sparse lighting of the halls in shadow, the piercing red glare of emergency exits, and city lights seen like a far off chaos from the purgatorial calm and relative security of the hotel interior.

It is a study of time and composition foregrounding shot duration and stillness to effect as often boring as hypnotic, – this being of course the point, to find the fleeting moments of poetry within the otherwise banal, and probably best seen in the captivity of the theatre for it – but also something less cruel than that, a movement of the structural film out of the vacuum of pure experiment, the closed and general spaces of the laboratory and museum, and into contact with a social and documentary reality, observing a specific social class in a specific city and hotel in a specific point in time on a specific night.

3. Je Tu Il Elle (1974)

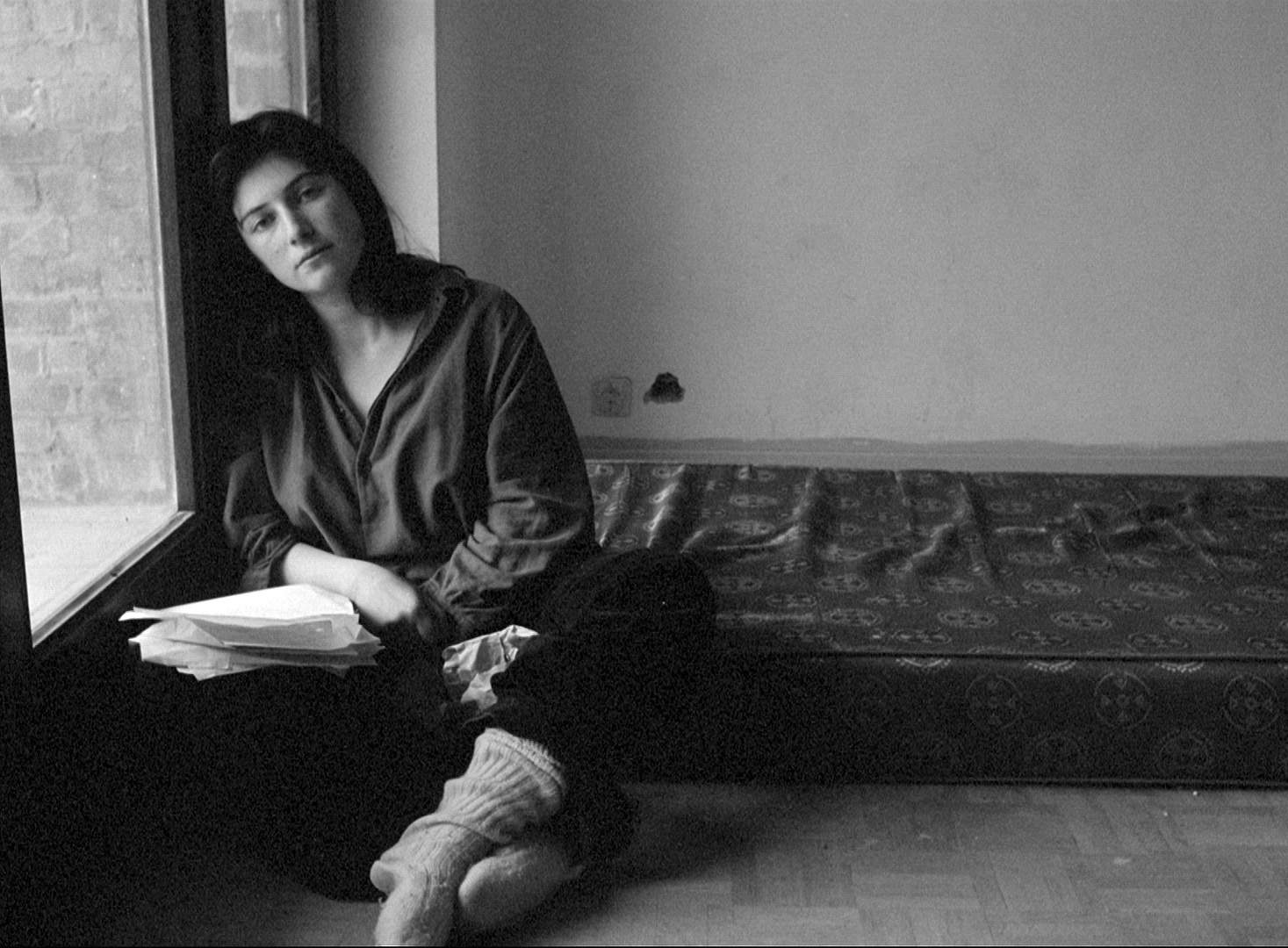

Akerman’s first narrative feature Je Tu Il Elle was a no-budget project starring Akerman herself and shot on reels of b&w 35mm stolen from a film lab, and sees an unnamed woman in the process of a strange self-dissection and four-way conjugation of self following a breakup, that begins in self-imposed isolation, leads to a road trip with a stranger (Niels Arestrup), and ends on a brief reunion with her ex-girlfriend (Claire Wauthion). In three parts the film is an abstract character study somewhere between the rigid formalism and conceptual play of the structural film, and the improvisational freeform of the French New Wave, exploring a theme of identity in flux, in both the vacuum of self and in relation to others.

The film opens on Akerman’s narrator in a despondent lethargy, holed up in the prison of a tiny room, emptied of furniture until only a mattress remains, subsisting for more than a month on only a bag of raw sugar. She writes a letter, then rewrites and rewrites it, as three pages become six become more than a dozen. We see her write, but never see or hear the contents of this letter. Meanwhile she narrates these events with a dispassionate almost scientific objectivity, and yet the narration constantly betrays what we see on screen, appears unrelated or disordered, or, as in her claims to repainting the furniture blue, then green, conveys information completely irrelevant to the black and white film viewer. It’s a kind of a joke, jamming the proper function of the traditionally authorial voiceover narration in a deadpan conveyance of the characters’ own dislocation. An isolated individual (Je) the narrator finds herself undefined by the mirror of any other, save for the silent recipients of her narration and her letter (Tu).

In the passing of a sudden snowfall the narrator leaves her isolation to hitch a ride with a long-haul trucker (Il) for an unannounced visit to her ex. We are never grounded in geographic reality. The pair seem to drive for days, stopping at truck stops and bars, as the trucker tells his life story to a suddenly silent narrator before engaging her in a sexual encounter that will serve for another temporary self-definition. Finally arriving at her ex’s (Elle) as if not altogether unexpected, she is told she can’t stay, made a Nutella sandwich, and then again engaged sexually in a brief return to a previous self-identity, and, in a ten-minute sex scene which follows, – transgressive for 1974, brazen to this day – 3 static shots of 3 sex positions run through 3 forms of relation, identities within identities.

4. News from Home (1976)

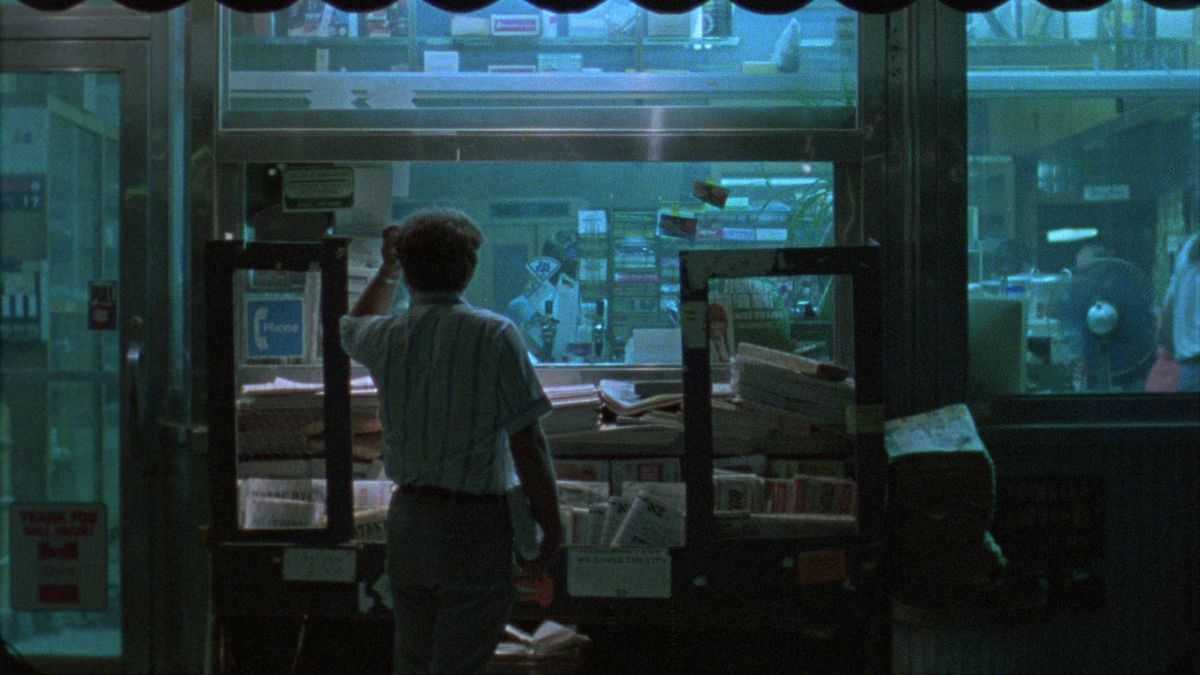

Half an epistle, News from Home is a structural experiment in autofiction, in which Akerman reads letters from her mother, sent during her first stay in NYC in the early 70’s played over structural-documentary footage of that same city in all its grandeur and distance from the content of her letters, evoking a sense of freedom and exile, homesickness and home outgrown.

The letters relate banal reports of family life, sickness and health, reports of her father’s business troubles and sister’s progress in school, and requests for Chantal to write back, to write more often, to send pictures. We never hear Chantal’s responses emphasizing the one sidedness of this communication. And the disjunction between image and sound evokes not only the gap between mother and daughter but also between cities, the speed and scale of NYC and the quaint, slow pace of Brussel’s old Europe. Akerman’s French narration too feels out of place matched to these American images, NYC from street level, not as seen by a gawking outsider but someone who’s found a home there – an American.

As the film carries on the narration is drowned out in city bustle and traffic, and begins to fade as memories of home become far off finally fading into a silence complete. A painful and perhaps guilt-ridden reflection on family, coming of age, and self-exile & in its visual present a patient time capsule of NYC and its denizens, city of garbage and dreams, high life and low in economic downturn, the birthplace of the filmic underground and home to the Son of Sam – long way from Brussels – and from the time of Akerman’s editing, a goodbye to the city too, found in its final image of departure, the city fading into a fog seen from a ferry moving slowly further from shore, end of another era, and another cause for homesickness.

5. All Night Long (1982)

Almost a narrative return to the liminal nighttime spaces of Hotel Monterey, All Night Long is a fictional panorama of dozens of characters played by a mix of professional and non-professional actors one summer night and early morning in suburban Brussels where Akerman grew up. Told in clipped fragments of narrative, its visual tableaus are windows on stories without context, intersection, or conclusion, and cobbled in part from observations Akerman recorded in notebooks as a teenager out on routine nighttime walks.

Across affluent and working class neighborhoods, the film finds its characters at home and on street corners, in all-night bars and cafes and is as much a portrait of the environment itself as anything. But even as Akerman approaches a study of nightlife – as opposed more broadly to the night – she remains in the margins far from the party, in a poetic space of dreams where anything seems possible that leads her to term it a “fantasy film” despite its realist grounding.

In underexposed green and blue we merely observe, and yet this is not documentary, not reality, but something like a world of Edward Hopper paintings come to life played out in parallel, that same sense of the banal and surreal, everyday spaces just a little too empty and still to be what they appear, figures just far enough away to be faceless, and careful compositions as if altogether incidental.