The ghost is a common motif depicted in the art, literature, and cinema. A cross-cultural phenomena, ghosts represent what we as humans tend to hide from. Of course, the thing we hide from depends within the context of each culture. What a ghost means in Japan, for example, isn’t the same as a ghost in Native American folklore. While the ghost’s mission depends on the situation, they all share the urge to reveal the mysteries hidden away with their death.

In every ghost story, there are many visual mechanisms and motifs to show the spiritual realm. Mirror reflections, bodies of water, and even the act of filming itself insinuate the presence of the supernatural. It’s no coincidence that these images share an emotional intangibility. Whether they remind us of trauma, wartime, identity crises, or grief, they are things we prefer not to think about on a daily basis. They are memories and emotions we repress.

Ghosts, like detectives of the spirit world, have a duty to reveal injustices made against them or their loved ones. No longer members of the material world, they have nothing to lose dredging up the past. Ghosts disobey the laws of nature to resolve unfinished business beyond the grave. Like vigilantes, they have no respect for the written laws on Earth and will stop at nothing until the truth comes out. The real horror then, isn’t the haunting or the shadow of death, but what’s repressed below the surface.

Ghost stories tell beautiful tales of desire and justice. They strive for a world outside of repression. Unfortunately, the secret gems of the ghost genre get clumped with the cheesy ones. But not all ghost stories rely on jump scares and played-out plot lines about a woman who fell down a well or an antique doll. There’s much more subtle, profound ghost stories out there.

Here’s a few of them:

1. Lake Mungo (2008, Joel Anderson)

In this Australian documentary-style film, director Joel Anderson explores neglect, disconnection, and loneliness. When Alice Palmer, a missing teenage girl, is found dead in a lake, her family members grieve her in different ways. Often glancing away from the camera or stumbling on their words, the characters struggle to speak comfortably. As the story unfolds, we start to see how disconnected the family is. This was important for Anderson. He gave the actors few lines and vague direction so that they would improvise. In turn, the interviews appear unrehearsed and awkward.

Anderson also uses found footage to create a tense family environment. He juxtaposes the footage with interviews. In one scene, for example, we see Alice yelling at the camera. Later, in an interview with the father, he recounts a time where he believes he sees Alice’s ghost yelling at him. Anderson starts to play with memory here, the element of film proof making it all the more confusing.

While many have compared Lake Mungo to Paranormal Activity, the film doesn’t rely on malicious, blood thirsty ghosts. The horror of Lake Mungo is much more existential. Anderson shows this with the family’s arch, or rather, lack thereof. Upon unearthing disturbing facts about Alice’s life, the family does nothing with it. Instead of confronting the terror, they repress it even deeper than before. Anderson shows this with two final, devastating interviews with Alice and her mother, who remains oblivious to her daughter’s dread.

2. Atlantics (2019, Mati Diop)

A directorial debut feature film from 35 Shots of Rum star, Mati Diop, Atlantics marries the spirit world with the material. At first glance, the romance seems simple. Ada and Souleiman, two young lovers, have to hide their relationship because Ada has been promised to an older, richer man. Meanwhile, Souleiman and his co workers seek rightful pay from a construction project. They plan to go to Spain to seek better work in Spain. He promises to return to get her once he returns from his trip. Ada hears no word and assumes the worst.

The route from Senegal to Spain is a common migratory route today. It’s difficult to get in legally, so many travel by boat across the Atlantic ocean. Diop, half Senegalese herself, employs the image of the ocean’s waves throughout the film. Fatima Al-Qadiri’s mysterious, synth music accompanies sunset-colored waves, instilling a haunting feeling. Many have died because of those waves, and better yet the borders that cut off safe passages to Europe.

Atlantics transgresses borders of land and water, man and woman, body and spirit. With Diop’s use of mirrors and water, she suggests the fluidity between characters, whether that means possessing the living to be with their loved ones or forming unions from beyond the grave so their families can get paid.

Atlantics won the Grand Prix at Cannes in 2019. In submitting Atlantics to the festival, she became the first Black woman to premiere a film in the competition.

3. The Spirit of the Beehive (1973, Víctor Erice)

Spanish director Víctor Erice depicts life under the Francoist dictatorship, while Franco was still in power. For this reason, the film makes ambiguous and suggestive references so it could get past censors and be filmed at all. In making the analogy of the beekeeper is to the beehive, what the father is to the daughter Erice expresses the inescapable control felt by Spanish people after the civil war.

The Spirit of the Beehive doesn’t name a specific ghost, but rather, shows the looming horror of repression the young protagonist, Ana, faces. Upon seeing Frankenstein for the first time, she ponders on the senseless death that happens on both sides. Ultimately, she sympathizes with the monster, even though he’s ostracized for his difference.

As the film progresses, Ana starts to mistrust her father. Just as a beekeeper looks from the outside in, surveilling the bees’ behavior, her father surveils her. Erice demonstrates this with the claustrophobic mise-en-scene, mimicking the structure of a beehive itself.

The Spirit of the Beehive tells the story of a ghost that still haunted many people when it came out. It won several awards and was permitted to circulate abroad, which was quite difficult during the Francoist regime.

4. Uncle Boonmee Who Can Recall His Past Lives (2010, Apichatpong Weerasethakul)

Based on buddhist abbot Phra Sripariyattiweti’s 1983 book, A Man Who Can Recall His Past Lives, Apichatpong Weerasethakul reflects on topics of reincarnation. Where most of the films on this list deal with topics of repression, Weerasethakul is more interested in what comes after moving past that fear. In a series of long shots, Uncle Boonmee immerses the audience in the spiritual, immaterial realm.

Uncle Boonmee takes on a beautiful, serene perspective on death. This tranquility is demonstrated through the characters’ matter-of-factness while speaking, the fixed camera movement, and its motif of nature sounds. For fans of Donna Haraway’s Staying with the Trouble, Uncle Boonmee reflects many principles of de-centering anthropocentrism. Remembering his lives as other animals besides being human and communicating with his son despite his non-human form are a couple of examples.

Rather than being a scary, finite event, Weerasethakul expresses the multifaceted pleasure in dying, being born again, and thinking of the future, whether there are humans in it or not. Weerasethhakul’s video art exhibition, Primitive, which Uncle Boonmee is a part of, expands and reflects on the spiritual universe shown in Thai folklore and culture.

In 2010, Uncle Boonmee won the Palme d’Or at Cannes.

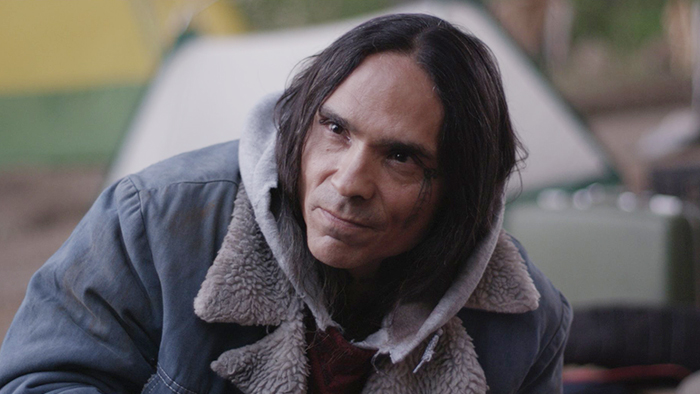

5. Mekko (2015, Sterlin Harjo)

Director Sterlin Harjo paints a derelict portrait of Native American life in Tulsa, Oklahoma. Touching on social topics of alcoholism, prison, and homelessness, Mekko (pronounced meeko) shows the pure desire shared among the Native community for a return to their original lands and way of life. Alternating between voiceovers spoken in Muscogee (Creek) and English for diegetic action, Mekko identifies a malicious spirit, or rather witch, in his community.

The body of contemporary Native American literature and media describes a post-apocalyptic ghost world. Considering that most Native Americans were murdered in genocide or forced to integrate with white American culture, the memory the community holds has been fragmented, poisoned, and trashed. Harjo conveys this loss of memory and identity in bookends, referring to the witch that poisoned Mekko’s community and forced them to evacuate, as told by his grandmother. While Mekko is dark, it leaves the audience with a hopeful, tender ending that’s worth seeing.

Mekko has won awards at TIFF, Santa Fe International Film Festival, and the American Indian Film Festival.