When we talk about movies, we’re often talking about directors. It’s an ingrained thing — it means we’ll ask somebody about their favourite Hitchcock scene or Scorsese’s recurring themes, but rarely about their favourite John Sayles script, except maybe when he’s also in the director’s chair. The writer in particular has been relegated to a position of obscurity disproportionate to his contributions, but there are some writers whose talent is so great, and their style so evident, that they can’t help but rise above their usual occult status.

Richard Matheson is the greatest of all of these. He’s a pulp auteur. A Twilight Zone alumnus who gave William Shatner some of his best dialogue. (“There’s some — thing! On the wing!”) He’s the unequalled, prototypical working writer, greater even than Robert E. Howard and Jim Thompson. He mastered not only the short story (“Long Distance Call”) and the novel (Hell House), but also the teleplay and the screenplay, the best of which will be mentioned here. If you don’t know him, you have no idea the enviable position you are in, as you’re able to experience these stories for the first time.

So, without further ado…

1. The House Of Usher (1960)

After Hammer Films had had success by revitalizing the Gothic horror of Universal’s early years, Roger Corman saw an opportunity to exploit another public domain property in a similar fashion: the short stories of Edgar Allen Poe. Hired on the strength of his novel I Am Legend and his adaptation of his own work, The Incredible Shrinking Man, Richard Matheson was the perfect fit for this kind of movie: a more literary take on the B-movies that given Corman and AIP their good names.

House Of Usher follows Philip Winthrop, due to marry Madeline Usher — or he would be, if her tortured, demented brother Roderick (Vincent Price) wasn’t so obsessed with ending the family’s dark lineage. Those familiar with the Poe story will know that this involves premature burial, insanity and, ultimately, total collapse. But Matheson adds his own touch to the story as well, by giving Roderick Usher a distinctive nervous malady: his senses are so acute that anything above a whisper drives him into hysterics. It’s this same nervous malady which plagues Madeline and which will drive Roderick to do evil, inhuman things.

Featuring one of the great Vincent Price performances, House Of Usher has been recognized as a classic by the National Film Registry, which selected it for preservation, and continues to be one of the most influential, startling and fascinating movies in the whole AIP canon. It’s also the perfect place to start with Matheson’s screenplays, showcasing his tendency towards tight, small-scale stories with simple plots and big surprises. But the best is yet to come.

2. The Pit And The Pendulum (1961)

Anything worth doing is worth doing twice. House Of Usher was such a success — in some ways, surprisingly so — that Corman and AIP elected to do it again, with a new Poe story, but bringing back Vincent Price and Richard Matheson. And sure, much of the movie is a retread of the first one, but The Pit And The Pendulum is more exciting, more gothic, and features an absolutely unhinged performance by Vincent Price. It’s the perfection of the formula.

The plot, you’ll notice, is basically the same. A young man comes to Vincent Price’s mansion looking for a woman, only to find Price still reeling from the effects of his familial sin. Like Usher, too, the Poe story forms the basis of the movie’s third act, if little else. But what Matheson does is fill the remaining hour up with tonnes of drama, intrigue and mystery, as the young man uncovers the macabre family secrets that lead to unexpected twists and turns and a climax unforgettable in its deviltry.

These two movies form the beginning of what would become one of the most legendary cycles in film history. Matheson would later team with Price and Corman again for Tales Of Terror and The Raven, but the first two are the undisputed classics, absolutely perfect in their combination of high camp and Gothic lunacy. Never was there a better argument for Matheson’s inclusion on the Mount Rushmore of great writers.

3. Die! Die! My Darling! (1965)

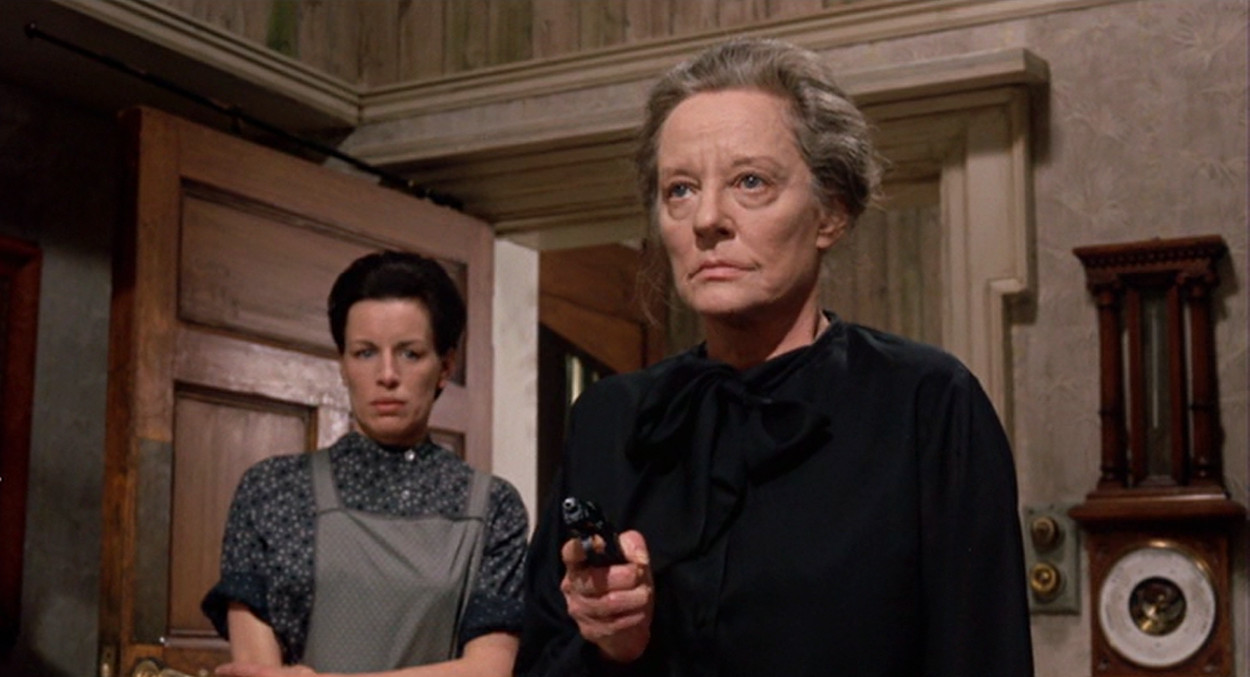

Hamer Horror doesn’t just refer to the company which changed the genre in the ’50’s and ’60’s — it refers to a whole type of low budget, atmospheric horror, at turns both bloody and restrained, well-produced and campy. That the writer of Corman’s Poe films would find his home here was no surprise, given Matheson’s predilection for writing contained, domestic horrors in familiar locales. But while Usher and Pendulum were both heightened period pieces about guilt and depravity, Die is about a much more human, more universal horror: the horror of fanaticism.

Stefanie Powers plays a woman who’s just been invited to her dead boyfriend’s mother’s mansion in order to commonly grieve the loss of her son, Stephen. But the mother is hiding a dark side to her personality — she’s possessed of a religious belief so black that she’s willing to imprison, starve and torture her son’s former lover until she learns piety. What follows is a horrific, claustrophobic nightmare as Powers’ character is forced into all manner of degrading acts, utterly unable to escape until she finds God or dies.

Released in Britain as Fanatic, the American title is perhaps best known as the basis for the classic Misfits song. What it should be known for is its intensity, its compactness, its ability to remain terrifying almost sixty years later. Die! Die! My Darling! is Richard Matheson writing at his blackest.

4. Duel (1971)

The short story upon which this movie is based — also called “Duel” — is a paranoid, uncanny thriller about a man convinced that a truck driver is trying to kill him. How much of it is in the protagonist’s imagination is never resolved, but Matheson still manages to carve out a thrilling, suspenseful car chase despite the fact that, for half of the characters, it might just be a routine drive cross country.

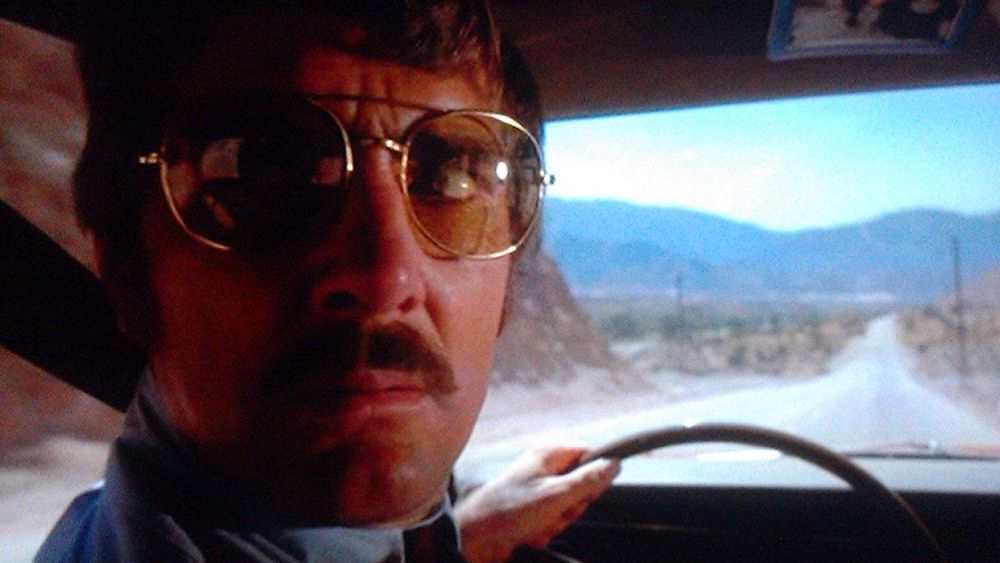

In the adaptation, the threat becomes much more real, but the driver’s reasons for wanting to kill remain undiscovered. In fact, we never see the driver at all — we only see the protagonist, the meek, unable-to-stand-up-for-himself salesman David Mann, in whose presence we remain from minute one through to the literally explosive finale. It’s with him that we’re trying to get off the road, trying every single thing under the sun to escape until there’s no other option but confrontation.

And really, that’s all it is: two men driving, one trying to kill, the other trying to survive. Matheson takes away every possible solution at every possible turn, whittling away all methods of escape one by one, letting us feel Mann’s anxiety as though it were our palms sweating all over the steering wheel. A truck has never looked so terrifying in all the hundred years of movie history.

Oh, and Steven Spielberg directed it. But don’t kid yourself — this is ever bit Matheson’s movie.

5. The Night Stalker (1972)

For the most part, Matheson’s heroes tend to be unassuming everymen caught in absurd situations. His Vincent Price characters may have been flamboyant, strange and tortured, but I Am Legend’s Robert Neville, The Shrinking Man’s Scott Carey and “Nightmare At 20, 000 Feet”’s Robert Wilson were all scared, mostly-average men, almost neighbourly in their unassumingness. But amongst all of that is the character Carl Kolchak, arguably the most interesting, well-rounded and engrossing character in all of horror fiction. It’s a character so fascinating he eventually got his own series, but before that he was in none other than the greatest TV movie that ever was, The Night Stalker.

Consider the beauty of its premise: Kolchak, a perennially disliked Las Vegas newspaper reporter, is on the trail of a serial killer he thinks might be a vampire. All manner of lunacy and drama emanates naturally from its simplicity, from the hookers being lured into dark alleys, through to the arguments between Kolchak and the cops. But most striking of all is the strangeness that comes from seeing a vampire walking along the Strip, the mixing of the modern with the ancient, the common with the impossible.

And at the centre of it all is Kolchak, with his porkpie hat, his white jackets and his impossible ego. People loved him: the movie was a big enough hit it warranted a sequel, The Night Strangler, which is almost as good. But the original reigns supreme.