Though initially describing the works of a particular movement of 1940’s and 50’s American crime films, ‘noir’ has come to represent a style derived from those films near ubiquitous in the palette of crime film and fused with all number of styles and genres besides.

Originating with an American appropriation of German expressionist aesthetics – a cinematic movement credited with spawning the first ever horror movie The Cabinet of Dr. Caligari (1920) and the first police procedural M (1931) – in the context of hardboiled crime films – in part by directors who worked in both German expressionism and American noir – the noir became America’s chosen expression of wartime cynicism with its cheap, blunt, and bloody stories told in the ambiguity of shadows, and showing cops, crooks, and private eyes all caught in the same webs of corruption and facing the same damnation.

This original run of noir which spawned classics The Maltese Falcon (1941), Double Indemnity (1944), The Big Sleep (1946), Out of The Past (1947), The Third Man (1949), and countless others lasted from the early 40’s till around the start of the 60’s where the crime film began to transition away from noir’s pulp expressionism towards the more documentary-style grit of 1970’s naturalism and the embrace of the action set-piece, the grand scale shootout and the car chase.

But as early as the 1970’s films like Chinatown (1974) were already pastiching noir into a genre beyond itself with the neo-noir, which would see a resurgence of popularity in the 90’s with L.A. Confidential (1997) and countless second-raters since. Meanwhile the noir was already being mixed with science fiction in Alphaville (1965) and Blade Runner (1982) establishing a filmic language of ‘cyberpunk’ as closely tied to noir, later manifesting in the smash hit The Matrix (1999), and horror, in Cast a Deadly Spell’s (1991) marriage of Raymond Chandler and H. P. Lovecraft, and a run of supernatural thrillers in the 90’s from Angel Heart (1987) to Jacob’s Ladder (1990) and The Ninth Gate (1999). Finally came the independent 80’s and 90’s integration of noir aesthetics broadly into the contemporary crime film, often in a self ironic way, removing noir from its period trappings with the films of Quentin Tarantino – especially Reservoir Dogs (1992) and Pulp Fiction (1994) – The Coen Brothers, Guy Ritchie, David Fincher, and their imitators.

But the noir was not always this versatile, and in its original form deviations from the hardboiled tradition – from the novels of Raymond Chandler, Dashielle Hammett, and James M. Cain whether in direct adaptation or spirit – were rare, and largely passed under the radar. Within its original run the noir did see a small breakaway genre which saw the integration of paranormal themes into the space of the noir. Different from horror films of their day, (even ones which, like The Spiral Staircase (1946) drew on horror’s shared heritage with noir in German expressionism and shared aspects of noir’s visual style) these paranormal noirs situated their supernatural fables or explorations of an occult underworld firmly within noir’s seedy tabloid realism.

In many of these films we see an exploration of psychological themes (in a way, another coming back around to German expressionism, with its own postwar obsessions with madness) that would later find their home in the 1960’s and 70’s psychological thrillers but were here dramatized extrinsically with the fantastic of supernatural phenomena; psychological disintegration not represented an internal struggle happening in isolation, but by the literal manifestation of their demons as external forces – demons, aliens, cat people. We also see an embrace of the mythology of the parapsychological – the psychologist or psychoanalyst as a recurring figure, a kind of noir priest or witch doctor for the scientific atheist, a male counterpart to the female fortune teller, who is also a recurring figure throughout these films.

Between these films, conceived of apart from one another – though some sharing a loose knit group of RKO filmmakers, producer Val Lewton, director Jacques Tourneur, director/editor Mark Robson, and the recurring Tom Conway, Ray Miland, and Elizabeth Russell – they seem to converge on a certain tone, a certain tension between the supernatural and the real, and a certain indirectness (probably due to the restrictions of the Hays Code) that defined itself a substyle or genre of noir completely of its time, never it seems to emerge again.

1. Cat People (1942)

Cat People from French-born master of the American noir Jacuqes Tourneur and the first project of producer Val Lewton is probably the most well known of the paranormal noir, and a strong early example of the Jaws principle that what you don’t see can be scarier than what you do. And what you don’t see here is any cat people, the human-beast hybrids never appearing out from the shadows for the b-budget Tourneur had to work with.

It’s the story of Serbian emigree Irena (Simone Simon) as she meets the American Oliver (Kent Smith) at the Central Park Zoo and the two quickly fall in love. To Oliver’s frustration, Irena remains distant, in belief that an ancestral curse will transform her into a murderous cat person if she gives in to sexual desire, or any strong emotion. She tells Oliver the story of how her people were enslaved by an invading force, and forced to turn to dark arts and satanic worship to regain some autonomy under oppression – and this, it seems, is what has left on her the curse of the cat people. Oliver thinks she’s crazy, and so does his coworker and friend Alice (Jane Randolph) who recommends the psychologist Oliver sends Irena to. But as her belief in the curse remains unshaken and Oliver grows tired of waiting for her, he grows closer to the open, all-American Alice, much to the jealousy and resentment of Irena.

Suddenly the film takes a turn – Alice, introduced as the has-it-all rival of Irena for Oliver’s affections suddenly becomes the film’s sympathetic protagonist, stalked by the now murderous Irena in a cat and mouse game of the film’s tense and shadowy latter half. At the behest of Val Lewton, Cat People even pioneers the horror movie staple of the fake-out jump scare.

2. Ministry of Fear (1944)

Fritz Lang was a legendary figure in German cinema and the development of German expressionism with films including Metropolis (1927) and M (1931) but fled to America after being offered a position as Minister of Nazi Propaganda – the party apparently unaware that Lang himself was a Jew. In Hollywood Lang found success as the director of many acclaimed noirs, such as The Big Heat (1953), but also the lesser known wartime spy thriller Ministry of Fear (1944) that used the madness and paranoia of wartime London to explore an occult substratum no less unreal by contrast.

Released from an asylum for the criminally insane Ray Miland’s Stephen Neale struts out into the bombing of London and immediately finds himself caught up in the machinations of a vast Nazi spy ring after winning a cake at a charity fairground containing a secret microfilm – evidently meant for a different winner. Pursued by sleeper agents from out of the crowd Neale enlists a drunken bumbling detective (Erskine Sanford) and the Austrian refugees Willi and Carla Hilfe (Carl Esmond & Marjorie Reynolds) to follow him through a paranoid underworld of resistance agents and infiltrators, propagandists, psychics, psychoanalysts, and spiritual mediums. A seance at Mrs. Bellane’s (Hillary Brooke) makes up a central scene where a voice from beyond the grave speaks of Neale’s dubious past.

For the unusual moral ambiguity of its protagonist and the omnipresence of the paranormal and the deceptive, Ministry of Fear reaches a rare fever pitch of confusion and destabilization for the American noir that hearkens back to the best of Lang’s gothic expressionist works, while playing on a mad manic streak that makes a comic absurdity of the spy ring operations.

3. Alias Nick Beal (1949)

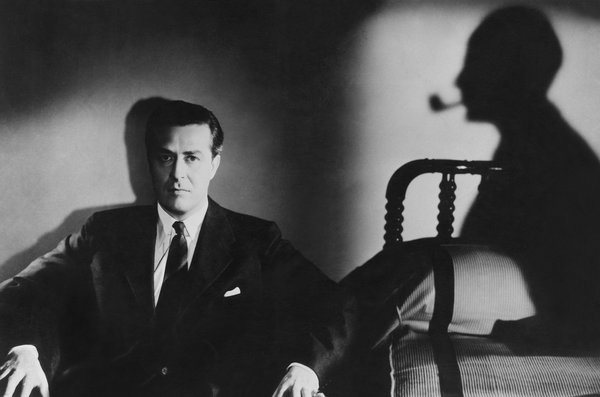

In Alias Nick Beal John Farrow (director of 1948’s The Big Clock) turns his noir stylings to a modern retelling of the Faust myth as a tale of political corruption with Ray Miland again as a show-stealing mephistopheles Nick Beal, as he sways the virtuous district attorney Joseph Foster (Thomas Mitchell) toward a path of darkness.

Long on the trail of the elusive underworld gambling kingpin Hanson, (so elusive as to not even be cast!), harangued by Hanson’s goons who seek to buy him out, and up for governor in the coming election, Joseph Foster is at his wit’s end when the mysterious Nick Beal manifests with a tip on where Foster can find some dirty documents on Hanson. But there’s a catch, it means break and entry, and Foster will have to loosen his rigid morality to steal them without a warrant. Reluctantly, he accepts, Beal asking in return only what Foster deems fair. We come to understand it is a game for Beal, who has chosen Foster for his very virtue, to prove the vulnerability of all men before the power, and tempting him, little by little, to a taste for immorality.

While Foster initially justifies his crime by a great good, he begins down a path of more and more selfish action, anguish, and the paranoia of an unclean conscience, much to the distress of his wife Martha, (Geraldine Wall) and his friend the reverend Thomas (George Macready) who thinks he knows Nick Beal from somewhere… Realizing he must do away with Foster’s moral anchor in Martha, Beal enlists by blackmail the ex-actress and prostitute Donna (Audrey Totter) the play the part of illicit suitor, to sabotage him by seduction.

Though somewhat predictable in its morality play unravelling Alias Nick Beal is bolstered by the sinister and sophisticated Ray Miland whose easy omnipresence sells us on its devil as a deal-maker.

4. Dementia (1955)

Dementia is a little known experiment in noir-horror from theatre manager and one time director John Parker, based on a dream of his secretary Adrienne Barett, who he cast in the lead role. It is the wordless nocturnal journey of a guilt-ridden woman (Adrienne Barett) through the streets of skid row LA like a gritty urban take on the dream films of Maya Deren. Pursued by a windblown newspaper and its ‘mysterious stabbing’ headline she seeks refuge from her demons while trying to avoid the police and the deranged inhabitants of the street.

Eventually meeting a sharp dressed devil figure (Richard Barron) she strikes a deal of sorts to be taken off in a rich man’s limo (Bruno Ve Sota) to be pampered and sheltered for the night. On the way she is visited by a faceless (uncredited) lantern-bearing spirit who shows her through a foggy graveyard, revealing at the graves of her mother and father and the ends that each have come to. Of course a deal with the devil never pays and so the woman finds her stay with the rich man turned quickly toward a violent conclusion as her psychology further frays and the film delves deeper into a nightmare space of persecution.

Written off by most Dementia would go largely unappreciated and get cheaply re-released under the name Daughter of Horror with a ridiculous Vincent Price-ish running commentary that undermines the power of the images and its haunting score by George Antheil and vocalist Marni Nixon. The film is full of potent symbolic imagery that lead it to being named “the first American Freudian film”, considered an early feminist work, and by some, such as writer/director Preston Sturgess (director of Sullivan’s Travels) a great unknown work. Never leaving the seedy street crime of its noir trappings Dementia is a psycho thriller way ahead of its 1955.

5. Invasion of the Body Snatchers (1956)

Perhaps best remembered for the 1978 remake it inspired, Don Siegel’s Invasion of the Body Snatchers is a paranoid alien invasion noir for cold war America, playing on fears of both communist subversion at home and the McCarthyite conformism that turn one’s neighbors into an enemy with its ‘pod-people’ who invisibly replace the residents of a small California town with perfect imposters of a hive-mind alien nature, with no conflict, no individuality, no emotion. Contrasting this extraterrestrial narrative is an undercurrent of psychological explanation, imposter syndromes and mass hysteria the cause of all the craziness.

And it’s protesting his insanity we first meet Dr. Miles (Kevin McCarthy) in the custody of police, – making his case to an asylum psychologist and telling the film’s story in flashback. It began when Miles was called back home from a conference when his clinic faced a sudden rash of patients – many of which being unusually unforthcoming with their problems. What Miles finds is a string of people claiming close relatives have been replaced by identical replicas, fears that they are suddenly changed in a way beyond perception, what Dr. Kaufmann (Larry Gates) Miles’ psychologist friend – whom Miles refers to as a ‘witch doctor’ – calls an epidemic of mass hysteria, apparently contagious.

The film relishes its slow buildup, creating a truly mad end of times atmosphere as the protagonists unaware move through the emptying public spaces, bars and dance halls. Miles is confused, but ready to buy the psychobabble until at the house of writer friend Jack’s house (King Donovan) the two find a body identical to Jack’s – as if in the process of forming. Determining the alien nature of the pods, and their replacing people in sleep, the two, along with Jack’s wife Teddy (Carolyn Jones), Miles’ girlfriend Becky (Dana Wynter) and the initially skeptical Dr. Kaufmann, the group bands together against the rapid turning of their town’s population into the pod-people.

But as the pod-people infiltrate the institutions trust becomes more and more frayed, the police, pod or not, apparently taking orders from pod-people in high up positions, the phone operators pod-people listening in on conversations and blocking crucial calls of the unturned. Soon Miles discovers the pod-people’s plan to transport pods across the country, – the spreading of disease, of ideology – and the mission becomes one of not only personal survival, but survival of the human race. Moving through crowded suburbia Miles and Becky must finally impersonate a now pod-majority population, walking stiffly down the street, giving away nothing. Building to a fever pitch of paranoia the film projects a mad summer heat, in the sweat slick shadows and atomic lights of the California night.