There is a moral in detective fiction perhaps put best by a slogan of The X-Files, a science fictional inheritor of the genre: The Truth is out there.

More than the conviction of evidence for extraterrestrial life this is in the context of the show, this phrase also speaks to a belief in objective truth, and the knowability of this truth essential to the entire detective genre, to the implication of forces which conceal it, and the moral imperative of its pursuit. This is the project of the detective, a knight errant of the modern world who seeks the hidden coherency of truth from out of a web of disparate and often contradictory clues and in finding it, restores some justice, order, or at least sense to the world.

Of course the genre’s moral core is often offset by its characteristic cynicism, where truth alone unbiased and pure may well be the only moral good. Where the hero is often positioned outside any law, private, unincorporated, as comfortable in the world of criminality as order, never above snooping, lying, breaking and entering, aiding or abetting in order to make a case, and devoted even to truth by profession alone, driven as much by mercenary selfishness as any moral force. Where the detective is just as often frustrated in their quest, if not by the all pervasive corruption of the law and its society of cheats, as in the ending of Polanski’s Chinatown, then by the ultimate inaccessibility of the facts. But even when frustrated, the detective still traditionally secures us within a world where truth exists as something objective and knowable and where there are those capable of and committed to its pursuit.

But what happens when the detective enters a strange abstracting space where truth is no longer knowable or based on objective grounds, where contradictory truths seem to coexist, where paranoid fantasy replaces intuition, and the process of detection itself becomes suspect?

These are the questions asked by a countercurrent of anti-detective films emerging in the 1960’s and 70’s art cinemas – striking a new resonance, and re-emerging in our current era of ‘post-truth’ – which in one way or another deconstruct the assumptions on which the genre is founded from the perspectives of a new skeptical relativism, not only as genre critique, but also as a repurposing of this now disemboweled form to new and creative ends.

Through it all the detective persists, stubborn holdovers as they are from a world where truth was absolute. There is another slogan in The X-Files: I want to believe.

Here is a list of ten anti-detective films to put Philip Marlowe on his ass.

1. Blow-Up (1966)

Michaelangelo Antonioni’s 1966 Blow-Up follows London fashion photographer Thomas’ (David Hemmings) inadvertent discovery of a possible murder plot in the shadow of one of his images, a photo of a couple taken in the park with what appears to be a gun portruding from the bushes. A young woman (Vanessa Redgrave) luring her older husband (John Castle) to his death — a classic noir set-up, this is Double Indemnity stumbled upon by a bystander. Or is it?

The further the photographer investigates the more ambiguity begins to enter into the picture. No murder is reported and no body ever discovered, the woman, once tracked down yields no information, and quickly disappears. Returning to the scene of the crime Thomas finds nothing in the way of evidence.

The photograph, blown up beyond its capture resolution pushes the limitations of the filmic grain. Is the pistol he sees evidence of something really there, or are Thomas’ eyes playing tricks on him, an illusory product of the human penchant for pattern recognition, the way the mind turns inanimate silhouettes into human figures in the dark?

The background presence of a recurring troupe of mimes throughout the film, their earnest games of tennis wherein the viewer and protagonist alike find themselves following the imaginary ball in play undermines the notion that seeing ought to be believing.

2. Inherent Vice (2014)

It would not be a proper exposition of the anti-detective without mention of Thomas Pynchon, one of the genre’s literary forebearers, whose satirical novels explore the world of conspiracy with equal parts sinister edge and levity, as does Paul Thomas Anderson’s 2014 adaptation of Pynchon’s hardboiled hippie noir Inherent Vice.

Set in a sunny California beach town in 1970, Inherent Vice is the Nixonite death of 1960’s optimism through the perpetually stoned eyes of P.I. Doc Sportello (Joaquin Phoenix) as he attempts to decipher an increasingly complex and improbable web of missing person cases, first real estate mogul Mickey Wolfmann (Eric Roberts) on behalf of Doc’s ex-girlfirend Shasta Fay Hepworth (Katherine Waterson), and then Shasta herself, and third man Coy Harlingen (Owen Wilson) all of which seem somehow related to massive suburban developments, a conglomerate of L.A. dentistry, a cartel of heroin manufacture and distribution, and the mysterious schooner Golden Fang that sits offshore of Doc’s idyllic beach and seems somehow to puppet and incorporate everything he comes into contact with.

The Golden Fang comes to serve as a kind of catch-all for all the evil, corruption, and broken dreams beneath the paving stones of Gordita Beach, both as conspiratorial revelation of the interminglings of power at the highest level, and as an oversimple scapegoat for a complex web of the socio-political ills that overturned the ideals of Doc’s generation.

And though Doc’s drug habits, hallucinatory episodes, and paranormal experiences throw his relationship with reality into doubt, as those around him disappear and die, what choice does he have but to believe?

3. The Man Without a Map (1968)

Hiroshi Teshigahara’s 1968 The Man Without a Map is the last of the director’s five adaptations of the work of Kobo Abe, whose surrealistic novels provided the basis of Teshigahara’s new wave classics The Woman in the Dunes and The Face of Another. The Man Without a Map was not met with the unanimous praise of the other two adaptations and might be in its own quiet way the most challenging of the three mind bending films.

In it Teshigahara explores the urban legend of the jōhatsu – or ‘evaporated people’ – the supposed phenomenon of mass traceless disappearances local to Japan and the subject of Shoehei Imamura’s 1967 docufiction A Man Vanishes.

The main character of Teshigahara’s psychedelic-tinged noir is an unnamed detective, played by a gangsterish Shintaro Katsu (best known for his role as Zatoichi in the series of samurai films) searching for one such evaporated man, Memuro Hiroshi, a salaryman in an unspecified part of the anonymous hypermodern sprawl who up and vanished on his way to work one morning leaving not a clue towards his whereabouts or a possible reason for leaving, only more than enough clerical evidence of his many past existences, licenses and certifications, receipts and office records, yet nothing adding up to the soul of the man, as if he had been an absence long before he was gone.

In this The Man Without a Map is a meditation on urban alienation in a pastel-plastic modernity, and the more time the detective spends retracing the missing man’s steps, and the closer he becomes with the missing man’s wife (Etsuko Ichihara). It is not only Memuro’s identity that begins to fragment, but the detective’s own, as the line between the two begins to blur.

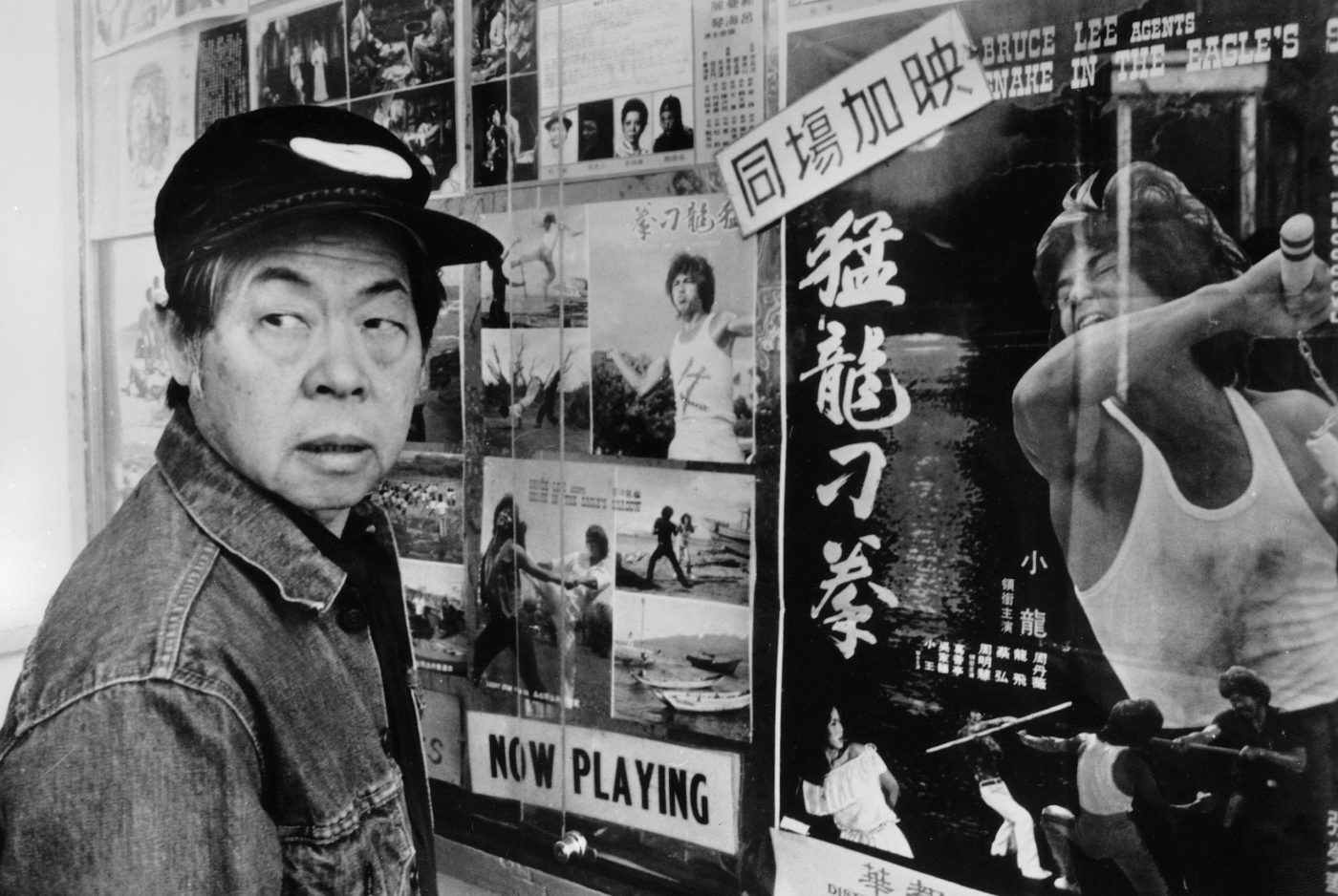

4. Chan is Missing (1982)

Chan owes Jo (Wood Moy) and Steve (Marc Hayashi) an independent cabbie’s license or else their $4000 back. But Chan has disappeared, back to Hong Kong rumors say, possibly on their dollar. His disappearance coincides with the eruption of conflict between Communist Chinese and independent Taiwan supporters over a Chinese New Year flag waving incident that has left one man dead. Steve thinks Chan has stiffed them, Jo thinks Taiwan nationals may have chased him out of the country, and both become concerned when a handgun is found in the glove box of Chan’s car.

This is the premise of Wayne Wang’s 1982 debut Chan is Missing, and sees the two men on a search for Chan through San Francisco’s Chinese community, where his many acquaintances and associates bring the audience through a kind of sociological survey of a tight knit world split on cultural-political lines and held in constant tension between tradition and assimilation.

Jo and Steve – a generation apart – play off one another like a comic duo, and are themselves an image of changing mores. The younger Steve who fought in Vietnam is cynical, staunchly anti-communist, against the influx of ‘new money Chinese’, and identifies more with mainstream America. The elder Joe sees in Steve a loss of his cultural self, and holds an outsider’s skepticism towards white America that prevents him from going to the police for help locating Chan – something he and Steve do not see eye to eye on.

The more the men discover about Chan Hung – his many jobs, the many things he meant to many people – the more fragmentary and unreal he becomes, the more allegorical and convoluted the case of his disappearance becomes as if the men are searching for a protean image of Chinese-America itself.

5. The Parallax View (1974)

Thematically the strongest of the post-Watergate conspiracy thrillers and directed by the same Alan J. Pakula of the Watergate-film-itself All the President’s Men, 1974’s The Parallax View finds investigative journalist Joe Frady (Warren Beatty) on the trail of the assassin of presidential candidate Charles Carroll, a political outsider whose independence made him dangerous to the establishment.

The film echoes not only the assassination of John F. Kennedy a decade earlier, but also the follow-up investigation of a two-shooter theory by district attorney Jim Garrison which lead to his trial of Clay Shaw, a New Orleans businessman implicated by Garrison in a vast conspiracy to kill the president for his ambivalence toward the anti-communist campagin and the threat this posed the military-industrial complex.

As Joe Frady investigates he traces the murder back to a ‘Parallax Corporation’, a faceless organization for ‘human engineering’ responsible for the recruitment of psychotics from among the population and their deployment as instruments of illegal political action.

The Parallax View is a look at the detective in a world where crimes are no longer committed by individuals but vast as if unmanned political and economic forces wherein no sole guilt can be located, and where all the banal evil of a political system can be dispersed across networks of disposable operatives and faceless corporate entities or governmental agencies, and individuals, like Clay Shaw, can only be tried as symbolic figureheads, punished to no effect, or let walk on a lack of personal responsibility.