We live in the age of “that shot”. Photojournalism can be made or broken by a key image that acts as the face of an article or portfolio. Social media is commanded by a specific take out of the hundreds we shot (it’s the single image that can make it to the end of our shoot, and go all the way online). Photography is nothing new, of course, and no amount of filters and devices can change its history.

The concept of the moving image (yes, movies) is a bit newer, but we’re still looking at more than one hundred years’ worth of innovation and magic. I think we all forget that we are actually witnessing countless photographs being slammed together to create the illusion of motion; I’m not insisting that we aren’t aware of frames, but we always get lost in films and are not conscious of every single one of these frames all the time.

Today, we’re going to revisit cinema as the living photograph medium that it once started out as. We’ve tackled the films with the best cinematography and strongest lighting on here before. We’re going one step further to look specifically at the films that contain the best lit scenes of all time. These are the definitive moments of these already impressively lit works.

These are the scenes that pushed the envelope enough to stick in your mind for eons. These moments either let the light soak in your soul, or the shadows drown you in misery. Here are the ten best lit scenes of all time (in chronological order).

As usual, keep in mind that all of these scenes will contain spoilers.

10. Nosferatu – Coming up the Stairs (1922)

German expressionism was a major movement when it came to the integrity that lighting could bring. Sets were no longer lit just to get the focal points in proper view: they were turned into symbolic statements. It’s debatable which movement or filmmaker started this particular use for lighting, but the German expressionist movement was a collection of works that embraced this notion to the point of changing the game.

In F. W. Murnau’s Nosferatu, the moment where Count Orlok ascends a staircase to claim his next victim. Orlok’s shadow is all that we see of him in this particular sequence, and it makes his attack all the more terrifying. His hands elongate when he reaches for doorknobs (or his prey). The dark bedroom allows his claw to come from literally the shadows in the final moments. This truly is the foundation of our nightmares.

9. Woman in the Dunes – The First Night (1964)

Niki has agreed to help an unnamed woman for one night before he leaves to go back home; he is currently staying over because he missed the last bus of the day. Maybe the use of darkness by cinematographer Hiroshi Segawa was meant to illicit deep premonitions of the manipulations Niki was going to experience (and discover he was entwined within).

Perhaps this was meant to be a more literal take; after all, both of these characters are deep within the earth, where light doesn’t creep in. All they have is a gaslight to show that they even exist in this sandy purgatory. It renders an introductory scene to the chemistry these two characters display all the more artistic. The real magic begins when the woman begins her nightly work of shoveling sand, which dissolves into Niko’s dream sequence. This lack of a connection to the world above is rendering us delirious!

8. Citizen Kane – Projector Room (1941)

One of my all-time favourite cinematic experiences was during my first watch of Citizen Kane as a young, naïve undergraduate film student. I wasn’t as familiar with older classics as I should have been. The newsreel moment in Citizen Kane, to me, was what the rest of the film was going to be like. Little did I know how pivotal that dynamic shift coming up was going to be.

As soon as the projection is done, we are catapulted into a darkly lit room, where Gregg Toland’s masterful lighting work has remained in my very core to this day. Rays seep in like heavenly beams. Every subject is a silhouette, like an anonymous populace wondering about the whole story of Charles Foster Kane. A blank screen emphasizes the dark shadows. It was the perfect introduction to a film that meant to break many rules; the rug was pulled from under us successfully.

7. The Night of the Hunter – Porch (1955)

Reverend Powell is one of the more disturbing villains in cinematic history, and that’s partially thanks to the mystique that Stanley Cortez pulled off with his insane cinematography. Rachel sits on her porch with a shotgun, waiting to strike at any second. In some shots, her silhouette (with just enough of a backlighting to make her still visible) is plastered on top of an obsidian view, with Powell creeping in from the depths of hell.

A candle is brought in, illuminating the scene; Powell vanishes like a ghost in the night. The flame is blown out, and all goes back to an unholy darkness. The sequence is woven together with additionally spectacular shots: an attic shot that looks like it came from The Cabinet of Dr. Caligari, shots of the house that exploit the vulnerability of its inhabitants, and close ups of an owl stalking its rabbit prey. The Night of the Hunter is so damn sinister.

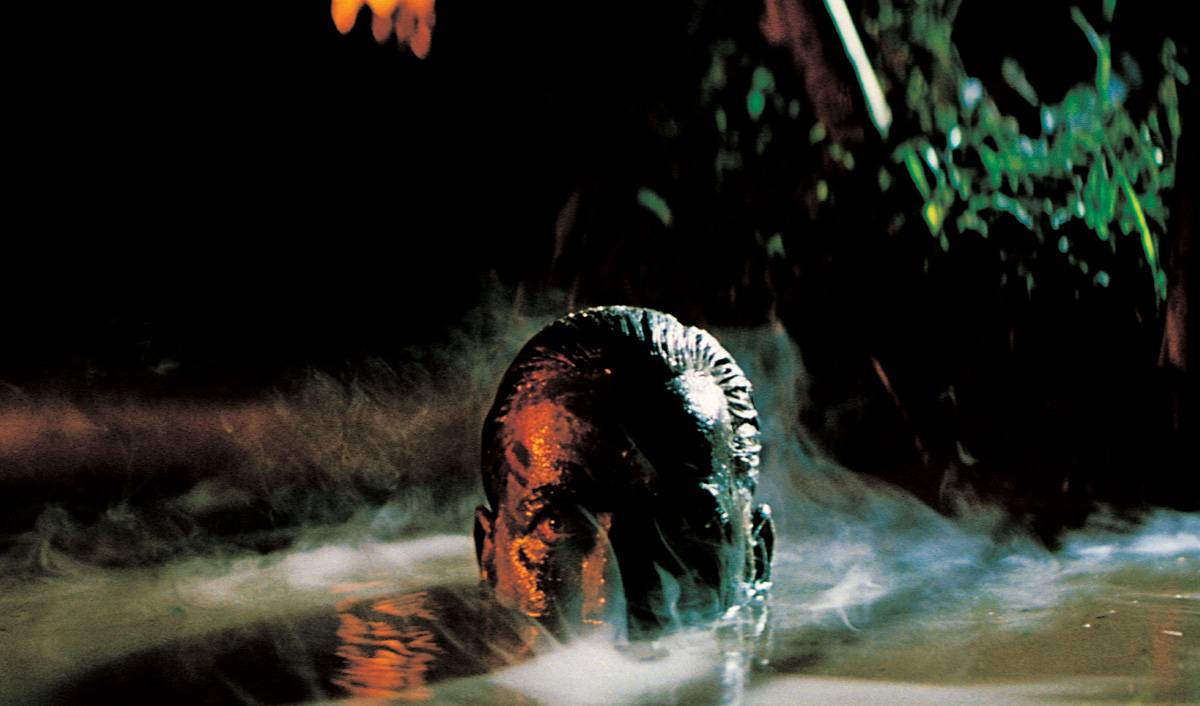

6. Apocalypse Now – Finding the Colonel (1979)

The influential lighting in Apocalypse Now was actually meant to be a work-around decision to block out as much of Marlon Brando as possible. Brando was meant to lose weight to play Colonel Kurtz; in typical Brando fashion, he refused. Francis Ford Coppola and Vittorio Storaro worked with what they had, and accidentally made the most dismal non-documentary film about the Vietnam War in existence.

The initial union between Kurtz and Willard is exceptionally noteworthy, as the darkness now proves that Willard’s mission was not over: he has actually wound up in hell. When Kurtz recites his off-kilter monologues, we are experiencing a peak level of delirium. Seeing this moment so far into a lengthy film (no matter which version you watch) only informs us that we are nowhere near a civil conclusion; after everything we’ve already scene, it is actually nauseating to think about. All of this comes from the lighting found in this late-introductory scene. It might be one of the most successful plan-b moves in film.