“Are you allowed to speak along the way? I was thinking there might be rules:” An introduction, being an attempt to link The House That Jack Built to the idea of art.

The greatest threat to cultivating cinema as an art form comes from about 99.99% of self-styled film critics and film buffs. What is taken for granted as signs of greatness in the veteran art forms? Art is not simply an impersonal industry pandering to the masses and the lowest common denominator, by offering them “entertaining” fight-or-flight superhero thriller/comic book films in order to make money.

Anybody opting for that path acts not as an artist but as an entertainer at best, a businessman at worst. More importantly – and this is discovered by the fact that not a single connoisseur or critic of any art form but cinema takes this position. Indeed, had the films being promoted as being the “greatest” been novels, nobody would pay them any attention – art is definitely not simply taking some predetermined and simplistic worn generic message or cliché that anybody with a half-functioning brain who has passed the age of 14 or so already understands and agrees with.

They simply present these via instantly-understandable stale and emotionally-empty techno-visual tricks and semiotic symbolizations and stylizations decodable within two seconds even by an eight-year-old or by the dumbest person imaginable.

Those seeking popularizations of philosophers’ and theoreticians’ abstract ideas, presented in such a way as to be easily-digestible to lay masses, have Wikipedia. Those wishing to delve deeper can always read philosophers’ books – and what is described sounds more like Sudoku than as an art form.

Real artists, at any rate, do not view themselves as inferior second-rate/second-hand “philosophers” with nothing original to contribute of their own, existing only to popularize real philosophers’ and theoreticians’ ideas (in other words, already-existing knowledge). If anything, they view philosophers’ abstract ideas as being inferior, not superior, to art’s view of life.

Art, as understood as such for millennia, is pretty much the opposite. It is, in simple words, a highly individualistic and personal form of psychotherapy, or, more exactly, an individual’s attempt, after having suffered what the experimental novelist Yosef Haim Brenner succinctly epitomized as the quintessence of art, namely, “breakdown and bereavement.”.

To understand those inner demons and acute suffering-inducing crises and problems in their personal lives of which they do not understand, asking questions rather than providing quick answers, as an arduous, slow, step-by-step, perceptual, and processual journey of self-discovery.

It is an attempt to perhaps know themselves better and to learn about themselves and their emotions, in order to maybe make some sense of these crises, or a genuine case of a lack of definitive knowledge that can spur only from losing faith in all other options provided by more conventional paths. It is, simply put, an open-ended endeavor, definitely not simply taking already-existing knowledge and popularizing it.

In other words, not only is all art by definition personal and autobiographical (not necessarily in the literal sense), but all art by definition is self-indulgent, as a real artist never creates work in order to pander to or to please an audience (let alone in order to earn money) other than themselves. All art, by definition, is a radical form of healing truth-seeking self-expression.

Small wonder that most great artists have been severely mentally ill (some suggest causality), or, at the very least, have found themselves to be strongly outside the normative social order. Only if the artist learns something about themselves, can their audiences hope to become more perceptive and perceptual with regards to human nature or to improve their lives and understandings of fellow humans and the world.

1. “Love is also an art form”

It is one of the most personal and autobiographical films ever made. The fact remains that, bar cinema, not a single art form has ever chosen this disembodied route. The “purely visual, purely cinematic” approach is that of a technician, not that of a humanist embedded within humanity.

In this , I should like to argue that “The House That Jack Built” is one of the greatest works in the history of the cinematic medium precisely because of its “un-cinematic” nature; namely, precisely because it does what is taken for granted in all other artistic media, yet is frowned upon by formalist/auteurist journalists.

Von Trier is, of course, the forerunner of the Dogme 95 movement. Just a few weeks before watching “The House That Jack Built,” I watched “Festen” (1998, Thomas Vinterberg), the first film produced by this movement, whose creed, to reiterate, is to simply do what is taken for granted in all art forms and ignore the macho cinema of “real men,” the infatuation with and fetishizing of techno-visual tricks and the lack of interest in emotions.

I was taken aback by the fact that it was simply impossible to do to that film what is so easy to do (and so easily taken as sign of greatness in most cinema circles) with Hollywood’s “cinematic gaze, language, devices, tools, and expression” approach. Instead, with this lack of “aboutness,” it did what is taken for granted in the other art forms (yet is so rare, and, indeed, considered radical, and frowned upon, within film circles): present the viewer with complex, confusing, and bewildering adult emotional situations that are impossible to easily classify and understand.

“The House That Jack Built” is neither a “plot” nor a “message” film, so these approaches shall naturally be jettisoned, as shall formalist/auteurist (and “film theory” i.e. political/ideological “social justice” politically-correct Foucauldian/Butlerian) approaches.

“The House That Jack Built” has virtually nothing to do with violence, and nothing whatsoever to do with serial killings, in much of the same way, and for much of the same reasons, as von Trier’s 2013 “Nymphomaniac” had almost nothing to do with sex.

Von Trier has suffered throughout most of his life from a variety of debilitating mental disorders – obsessive-compulsive disorder (OCD), major depression, various phobias and anxieties, etc. – and “The House That Jack Built” is his attempt, his most autobiographical and personal to date, to deal with these disorders.

Frequently, like several of his earlier films, it feels almost like an apologia or a reply to his detractors, those who simply cannot fathom why he decides, time and again, to do what is taken for granted in all art-forms rather than simply picking grand predetermined themes and popularizing them via “cinematic language, devices, and tools, and the cinematic gaze.”

Someone like that has better things to worry about than predetermined camera angles/positions/movements pregnant with meanings, apodictically stated rather perceptually/perceptively lived through, instantly-decodable as such within seconds.

The film it most resembles is Marian Dora Botulino’s “Melancholie der Engel” (2009), though several other relatively similar attempts could also be named, among them:

Glauber Rocha’s “Deus e o Diabo na Terra do Sol” (1964); Chantal Anne Akerman’s “D’Est” (1993), “Sud” (1999), “De l’autre côté” (2002), or “Down There” (2006); Gaspar Noé’s “Seul contre tous” (1998), “Enter the Void” (2009), or “Climax” (2018), Tali Shalom-Ezer’s “Princess” (2014); Amos Gitaï’s “Esther” (1986), “Berlin-Jerusalem” (1989), or the TV series “Architecture in Israel” (2013); Guilhad Emilio Schenker’s “Madam Yankelova’s Fine Literature Club” (2017); Ram Loevy’s TV films “The Bride and the Butterfly Hunter” (1974), “Hirbet Hizah” (1978), “Indian in the Sun” (1981), “Bread” (1986), or “Crowned” (1989).

Most journalists lack even a semblance of a way to approach such an “un-cinematic” work, instead defaulting into viewing it through the same prism they analyze Hollywood’s “philosophical” explosion-fests/thrillers.

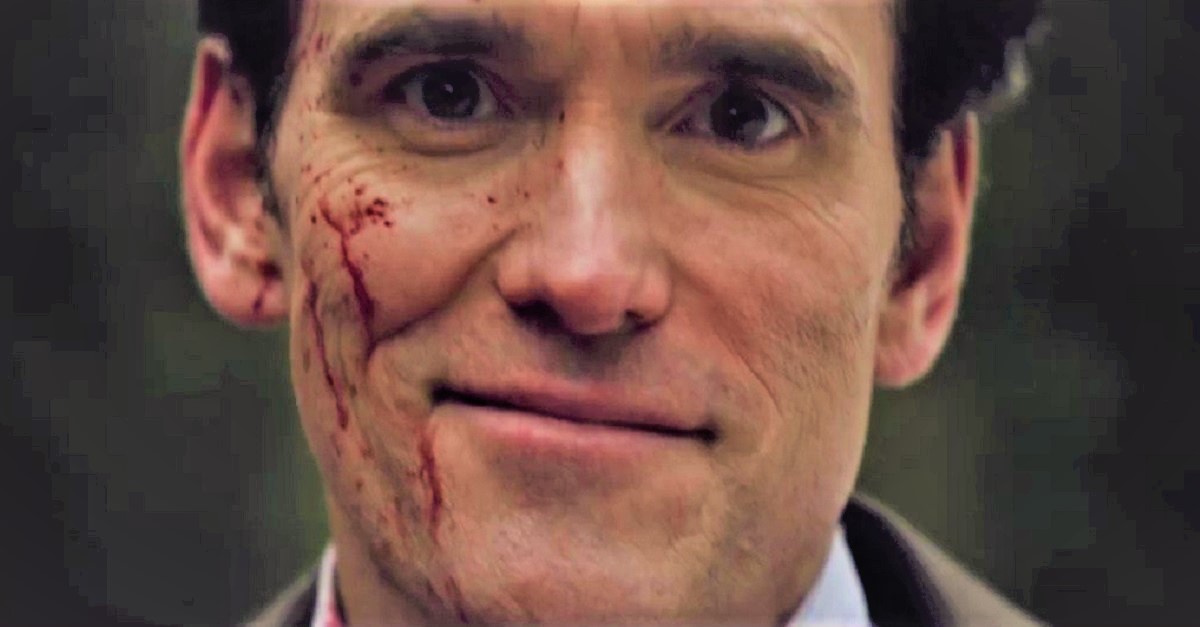

It was, instead, a very life-affirming (I am saying this without even a modicum of sarcasm) and very tragic look, similar to the films outlined above, into one man’s – Jack (Matt Dillon) is Lars von Trier – attempt to regain his humanity and reconnect with the world and the human spirit. He does it through an act of love (not in the romantic/sexual meaning of the word), in an attempt to deal with the world’s abandonment through self-discovery and self-destruction. To avail myself of an atrocious, infantile, now-ubiquitous (and rather ridiculous) metaphor, it is about “the red pill.”

2. “Look at the art:” It does what is taken for granted in the veteran art forms, yet is frowned upon by formalist/auteurist journalists (and is hence so rare in cinema)

Jack is not what you would call a “normie.” He is completely lonely in his life, unsatisfied with his job, has no real friends and no family, his love life is in shambles, and, most importantly, he suffers from OCD, various anxieties and debilitating phobias, and possibly also depression (though, is he really a soulless psychopath, or, a heroic figure?). The “normal” world has rejected him, yet he just wishes to be loved and to be accepted as an equal in this world’s playing field, and so, detached from the social order, he must try to attempt to deal with it and these. And he turns to art.

He first tries to build a house, yet he never really achieves this. Who are Jack’s victims? Precisely the symbols and metonyms of the “normal” word, of political correctness and “social justice” “victimhood” (the #MeToo parallels are ominous, as are a certain American president’s) and of bourgeois respectability, “preciousness,” “(social) importance,” and propriety.

This comes to fruition with verisimilitude and poignance in various ways within the first incident – the proper, bourgeois unnamed “bitch” (Uma Thurman) is so conceited and condescending in her brazen emasculation (we will get to that) of Jack.

Though, most importantly, throughout the second (wherein Jack cannot but simply help himself, and must “perform” impulsively, and take further risks, in order to alleviate his OCD and his pain and suffering, in order to attain, crying, the protection of a higher power, his ultimate mode of therapeutic self-expression); and the third, in which a flawed, broken individual like von Trier himself (who, just to be clear, shows us a slideshow of several of his earlier films while Jack talks about art), Jack deals with and attempts to handle and to surmount his issues via artistic expression – destroying the “normal” natural world itself.

3. “Your house is a fine little house, Jack:” It deconstructs the Hollywood dream/fantasy machine (and how it entraps us)

“Dancer in the Dark” (2000) was up until now von Trier’s major attempt to delineate and demarcate what differentiates his artistic approach – and it should be clear by now that he is one of the greatest artists the cinematic medium has ever produced – from Hollywood’s “cinematic gaze, language, devices, tools, and expression” approach (just as 2009’s “Antichrist” and 2011’s “Melancholia” were his greatest attempts up until now to deal with his mental problems).

Publius Vergilius Maro (Virgil, here called “Verge” and played by Bruno Ganz) serves here (aside from accompanying Jack to hell, as in Durante di Alighiero degli Alighieri’s “The Divine Comedy,” and there are also references to Johann Wolfgang von Goethe) as a foil (akin to Seligman’s character vis-à-vis Joe in “Nymphomaniac”), representing Mr. von Trier’s detractors and upholders of both political correctness and the Hollywood approach.

While Verge eventually concedes that Jack did indeed manage to show him something he did not know beforehand, Jack, discussing his theory (he is an engineer and inspiring architect, after all) that the material (for the house he tries, unsuccessfully, to build) has a will of its own, decided to leave this world, consenting to follow Verge to hell and to be shot by the policemen, only after, at Verge’s insistence to find the material and let it do the work (as it is going to be a little bit difficult to build the original house during the raid), he managed to finally build the house out of all the corpses he amassed throughout this film.

This represents the fact that “The House That Jack Built” is art qua psychotherapy for von Trier no less than for Jack (this is the fifth incident): by leaving Hollywood’s instant methods (these are laughed at several times throughout the film: “he represents art”), only then can he peacefully exit the world and become his own final artistic (i.e. self-expressive masterwork, that is, by finally becoming an artist).

The image of Jack crying during the epilogue while reminiscing of his childhood during his sojourn to hell, understanding he will never get into heaven, is indelibly one of the most moving. In this sense, the film is optimistic and has a life-affirming, happy ending. It suggests one can always triumph via art’s redemptive self-expressive soul-healing and soul-searching qualities.

“The House That Jack Built” is thus in and of itself an affirmation of the artistic approach and a reproach of Hollywood’s “cinematic gaze, language, devices, tools, and expression.” Now, what about feminism?

4. “The Elysian fields:” It negates political correctness

“Why is it always about the men?” asks Jack, during the fourth incident, in one of the film’s most divisive moments. While cutting the naïve Jacqueline/“Simple”’s (Riley Keough) “great tits,” another blow at the chattering/middle classes’ windbaggery, you are supposed to cheer him.

Why are men assumed to be devils while women are assumed to be angels, asks Jack? Art is meant to shock people out of their complacent belief systems; the cold reception this scene got insinuates at the problems our politically-correct times have with traditional art. I believe the only hope for the future of cinema as an art form is for hyper-masculine dudebros to find another hobby.