The genre of horror remains one of the most interesting schools of cinema. The very idea of what audiences conventionally deem “scary” has seen countless transformations since the birth of the genre. From the intense stylization of Italian Giallo, to the grotesque senselessness of torture porn, filmmakers constantly strive for newer and more innovative methods to strike fear into the hearts of audiences around the world.

Nevertheless, horror is a genre fundamentally built not on evolution, but on tropes. On elements of the genre prior established by master filmmakers, now perceived to be staples of what constitutes an effective horror film. We have all at least heard of masterpieces such as Alien and Psycho, incontestable classics of the genre, but this list aims to highlight something different – the more obscure films of the genre, films take aim to break the conventions of horror, films that above all else, deserve more attention.

These films that dared to reinvent, all powerful expressions of genius behind the camera that are, quite frankly, worthy to be held in the same regard as some of the genre’s greatest.

These are 10 great horror classics you’ve probably never seen.

10. Altered States (1980)

The proverbial war between science and religion, between the subconscious self and the conscious self, are all interesting thoughts that certainly would give rise to some degree of complex discussion, especially in the medium of cinema. Ken Russell’s Altered States attempts to further this debate by exploring these ideas through the cinematic lens of horror.

The film follows an eccentric scientist obsessed with finding humanity’s true purpose, resorting to drugs and sensory-deprivation chambers in hopes of consciously unlocking the true potential of his subconscious mind. The premise does admittedly seem ripped from a superhero origin story, but the experience offered by Altered States is far from family-friendly.

A film that utilizes the celebrated methods of 80s horror to explore its themes, Altered States is a truly haunting abomination of body and psychedelic horror. Ken Russell made a film that dared to ask bold questions with the aim to challenge the mind, but the film doesn’t quite impart explicit answers to these intriguing questions, it imparts horror.

9. Jigoku (1960)

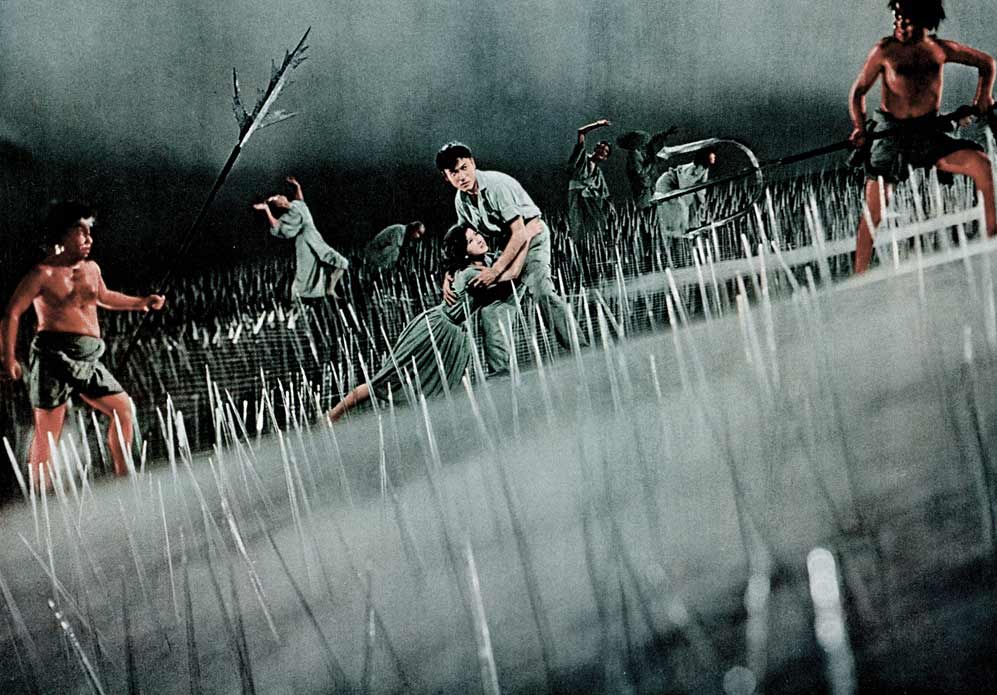

Is there a phenomenon in our society more terrifying than Hell? The idea that an eternity of suffering awaits after one’s mortality is a truly unsettling thought, and Nobuo Nakagawa immaculately captures this horrific notion in Jigoku. Also titled as “The Sinners of Hell”, Jigoku examines the spiraling nature of sin, set against a nuanced character piece propelled into fruition by an ill-fated hit-and-run.

Despite an unassuming runtime of under 2 hours, Jigoku does adopt a considerably slower pace as compared to more conventional films, sparing no expense in its exploration of man as a canvas waiting to be stained by immorality. Like any great J-Horror, the film’s command of atmosphere is sublime and expressive, painting an unsettling mood just a few degrees shy of the uncanny valley, and the film essentially achieves this unique undertone without an overreliance on supernatural elements. At least for the most part.

When the narrative inevitably reaches its crescendo, the horrific madness presented on screen, visuals that seem ripped straight out of a painting by Bosch, is certainly memorable enough to warrant a place in film history.

8. Cemetery Man (1994)

There’s a special kind of horror cinema known as the camp film. Films that garnered cult followings through peculiar exaggerations of genre elements, a truly unique approach to filmmaking that bridges gaps even between contrasting genres. Cemetery Man is one truly noteworthy film of this enchanting subgenre.

This classic of 90s Italian cinema offers a unique perspective of death, explored in such a bizarre and over-the-top method that defies all genre constraints. The film regards death as a central element to the plot, presenting the idea both with great importance as well as a much more disparate sense of nonchalance, with a narrative that dares to jump back and forth between the two extremes.

Cemetery Man is a film that essentially refuses to abide by the conventions of storytelling. Though the narrative and tone remains thematically and stylistically inconsistent, what ensues is an experience that coherently replicates numerous styles of horror, from zombie to body to psychological, giving rise to an experience that certainly succeeds in entertaining with the camp factor alone, even if it does fail to explicitly incite fear.

7. Kwaidan (1965)

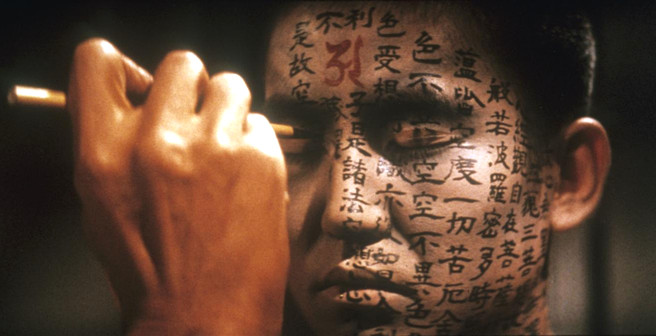

The Golden Age of Japanese Cinema has seen the likes of Ozu and Kurosawa grace the silver screen with their groundbreaking triumphs that truly set the standard for what cinema can truly be. However, there is one filmmaker active during the period that isn’t quite held in the same regard as his contemporaries, even in spite of an oeuvre matching the same level of quality as his peers.

Masaki Kobayashi’s anthology horror Kwaidan is a true classic of the genre and essentially paved the way for modern J-Horror, solidifying numerous elements such as the black haired ghost as well as supernatural rituals, all considered staples of the subgenre today. Kwaidan presents these now-iconic elements of the supernatural as less of an opportunity for fright and more of as a poetic character study, one that delves into facets of the human condition.

As such, Kwaidan serves a purpose far greater than horror alone. It’s an embracement of Japanese culture and their unique way of life, with Kobayashi exploring his roots through a series of colorful tales centered around tradition, essentially using the genre of horror as a medium to explore the conservative ideas of love, faith and honor.

6. Henry: Portrait of a Serial Killer (1986)

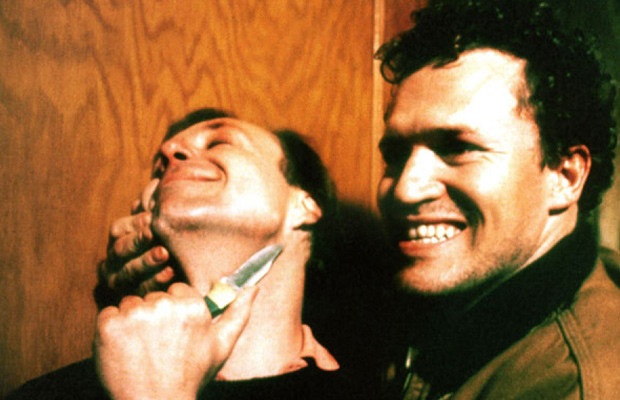

How does a filmmaker make an audience care for a character that’s inherently evil? John McNaughton understands that you can’t. It’s impossible to make a product of sin truly likeable beyond a superficial level, at least not without gratuitous stylization. Henry: Portrait of a Serial Killer is the very embodiment of this ideology. A film that genuinely understands this characterization. A film that, against all odds, imparts an experience centered around a truly evil character.

This is not a character study film. There is nothing redeemable about the titular Henry that even deserves discussion. This film is an examination, a study not on the complexities of the character, but one to highlight the depravity of man. Henry may have his moments of innocence, of three-dimensionality, but the film never explores these moments beyond their given scenes. It doesn’t justify or gratify that which is objectively immoral, it merely presents it with an understanding that we, as a rational audience, would be intelligent enough to discern right from wrong.

True one-dimensional evil is as much of a product of fiction as one-dimensional good. That is the true horror of Henry: Portrait of a Serial Killer, because the delusion of one-dimensional evil, as depicted in this film, is one tainted by shimmers of redemption, which consequently, makes this the closest, most honest rendition of how such an incorrigible sense of wrong can possibly exist in reality.