15-19. John Cassavetes’s Shadows (1959, for Ben Carruthers, Lelia Goldoni, and Hugh Hurd), Faces (1968, for John Marley, Lynn Carlin, Seymour Cassel, Fred Draper, Val Avery, and Dorothy Gulliver), and A Woman Under the Influence (1974), The Killing of a Chinese Bookie (1976), and Opening Night (1977, for Gena Rowlands and Peter Falk)

John Cassavetes, cinema’s impressionistic answer to John Zorn, Henry James, D.H. Lawrence, Edgar Degas, or Paul Cézanne, never attended film-school and hence emptied his films of reptilian “plots”/“storytelling,” grand messages understandable within a second by decoding visual metaphors, camera-engendered privileging of one character’s worldview over the other beloved by formalist/auteurist journalists, and shortcuts-to-emotion substituting the hard work necessary (on the viewer’s part) to work out characters’s and their complex/challenging emotional states with camera angles requiring no knowledge of life and emotional maturity to “get” doing it for them in a minute or two.

Knowledge in Cassavetes’s films – about the differences between men and women, self-deceiving images one creates and masks one wears that stick themselves so hard they replaced whatever remained, Man’s methodologically-individualistic responsibility for situations and ability to fully create them indomitably rather than “systemically”-embedded political “oppression,” and the ridiculousness and over-simplicity that the aforementioned Hollywood-style filmmaking comports so strongly it becomes part of our lives (in what kind of adolescent-macho world are we living that the considerable majority of the “greatest” films not just on IMDb’s Top 250 page but even on nominally more serious lists are about gangsters/mobsters and their explosions/car chases?) – necessitates life experience and comes in the form of faces, bodies, vocal/verbal/tonal shifts and turns, character/psychology/ emotion/feelings, etc., with the camera being entirely functional.

These films have the ability to teach us much more than those of any Hollywood directors screaming their intended and overdetermined meanings and ways of understanding so harshly it pierces ears. Cassavetes worked like a poet, composer, painter, and novelist i.e. by doing what is taken for granted in any other medium but is frowned upon by Hollywood-slavish formalist/auteurist journalists, not by predetermining every action happening in front of the camera beforehand (let alone predetermining camera positions/angles pregnant with meaning!) but by working step-by-step with the human face, body, and voice and deciding on-stage to do what seemed most emotionally-interesting and profound at the moment as a way of self-exploration, rising questions pertinent to crises rather than easy solutions.

Carney: “there is no point in writing, casting, directing, and editing a film if you know in advance where you are going to come out, how you feel about your characters and events, and what it all means[,] [i]f you can storyboard your film, save your time (and that of your actors and crew), skip the shooting, and publish the story-board[,] [t]here is no need to make the movie[,] [if] you don’t learn anything, no one else will either[,] [i]f you don’t change your feelings about your characters and events as you go along, your audience won’t either[,] [i]f your mind isn’t twisted into pretzels, theirs won’t be either[,] [i]f your heart isn’t torn and conflicted by the situations your characters are in, you haven’t created complicated enough situations[,] [y]ou’ve reduced life to the ‘lite’ experiences television or the newspapers give us[.] [Hollywood] represent a button-pushing sense of art where the only goal is to force the viewer to jump through a set of pre-programmed emotional hoops[,] [a]rt becomes a game of emotional tiddlywinks where you’re judged not on whether anybody actually got anything valuable out of the whole experience, but on finesse points–on how well you keep the nonsense moving right along[,] [t]he director and producers decide what points they are going to make before they begin[,] [t]hey cast, shoot, and edit the movie so as to be sure to make them[,] [t]he experiences in these films are canned[,] [n]obody involved in them–from the writer and director to the actors and editors–actually learns anything new[,] [n]o one changes his mind[,] [n]o one is forced out of his or her old patterns of understanding[,] [t]he only sermons the director or his viewers stumble on are the ones he’s already cleverly hidden under his own stones when he began[,] [a]ll valuable acts of expression are acts of exploration[,] [f]ilm the parts of your life you don’t understand[.] The moral of the story is that there is no reason to apologize if a viewer has to see your movie two, three, or more times, or to struggle for months or years to work through it emotionally.”

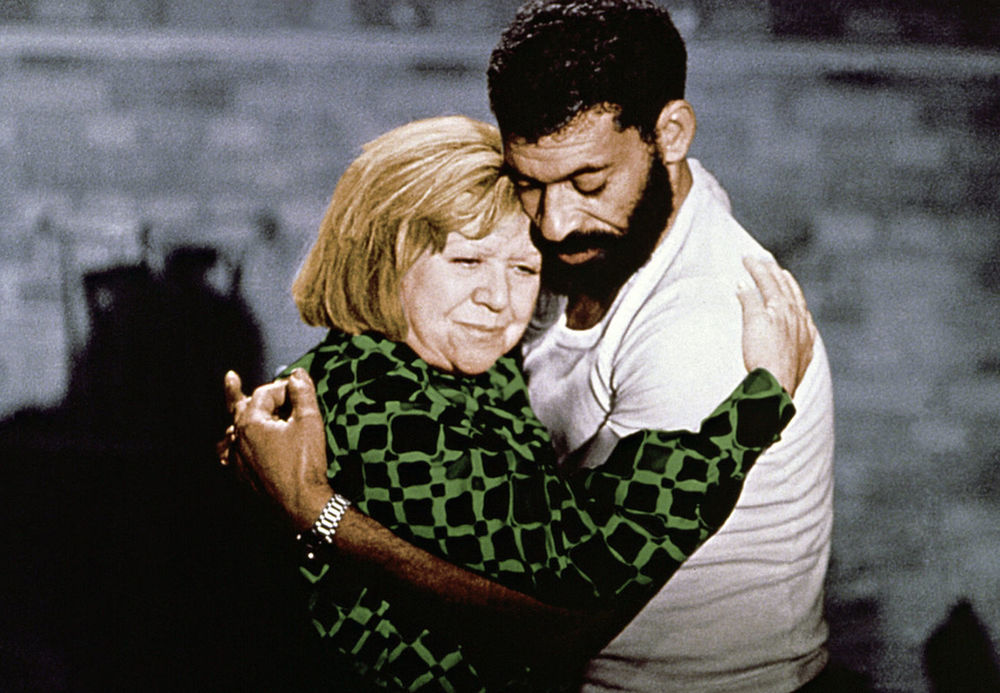

20-21. Rainer Werner Fassbinder’s Angst essen Seele auf (1974, for Brigitte Mira, El Hedi ben Salem, Barbara Valentin, and Irm Hermann) and Helma Sanders-Brahms’s Deutschland bleiche Mutter (1980, for Eva Mattes and Ernst Jacobi)

It has been extremely difficult to decide which films out of the many masterpieces from these two equally-talented titans of German cinema (though Deutschland bleiche Mutter is criminally-underseen with a mere 553 votes on IMDb!) to opt for but c’est la vie.

The former about a romance between an elderly working-class naïve German widow and a Moroccan migrant laborer, the latter about the emotionally-harrowing tribulations of one German couple (loosely based on Helma Sanders-Brahms’s parents) during WWII, both films eschew blaming “the system” for being as futile as blaming witches and present their character as sympathetic, albeit flawed, human-beings rather than hapless and angelic black-and-white victims.[1]

22. Aldo Fabrizi, Anna Magnani, and Marcello Pagliero in Roberto Rossellini’s Roma città aperta (1945)

As with the previous entry on this list, it has been rather difficult to decide which film to include from this master of emotion. Critic Irene Bignardi wrote in her Criterion DVD insert that this film “is not just a milestone in the history of Italian cinema but possibly [one] of the most influential and symbolic films of its age, a movie about ‘reality’ that has left a trace on every film movement since[,] [i]t is also the story of a fascinating and atypical adventure in filmmaking, a masterpiece malgré soi, a unique piece of cinema that was the result, in a way, of serendipity,” while critic David Forgacs wrote that “[good] (hetero)sexuality lines up in the film with good (anti-Fascist) politics and bad (homo)sexuality with bad (Fascist) politics[,] [there] is an implicit gender system in the film where masculinity is correlated with inner strength, femininity with inner weakness,”[2] a by-now politically-incorrect and old-fashioned view lost to history leading us straight to the next entry.

23. Paolo Bonacelli, Giorgio Cataldi, Umberto Paolo Quintavalle, Aldo Valletti, Caterina Boratto, Elsa De Giorgi, Hélène Surgère, and Sonia Saviange in Pier Paolo Pasolini’s Salò o le 120 giornate di Sodoma (1975)

Salò o le 120 giornate di Sodoma, described by some as the summation of the entirety of Western civilization, ends with a recitation of the following poem by Ezra Pound (Canto XCIX) set to images of sadistic necro-pedophilia: Rail; scold and ructions; manesco / and the whole family suffers. / The whole tribe is from one man’s body, / what other way can you think of it? / The surname, and the 9 arts. / The father’s word is compassion; / The son’s, filiality. / The brother’s word: mutuality; / The younger’s word: deference. / Small birds sing in chorus, / Harmony is in the proportion of branches / as clarity (chaoI) [3] The four fascist libertines rounding up the children cite Friedrich Nietzsche’s Zur Genealogie der Moral: Eine Streitschrift [4], Charles Baudelaire[5], Marcel Proust[6], Dante Alighieri[7], and the Marquis de Sade[8], making this film one of the most-intellectually choke-full in cinematic history.

24. Heinz Schubert in Hans-Jürgen Syberberg’s Hitler, ein Film aus Deutschland (1977)

The ultimate “uncinematic-merely-filmed-theatre-and-poetry” emotionally-profound experience and critic Susan Sontag’s favorite film [9], composed of little more than actors reading longwinded monologues – many in the style of Western political-incorrectness ranging from Immanuel Kant, Arthur Schopenhauer, Alexis de Tocqueville, Georg Wilhelm Friedrich Hegel, Oswald Spengler, Carl Schmitt, Max Weber, Otto Weininger, and Martin Heidegger to Hans-Hermann Hoppe, Paul Gottfried, Martin van Creveld, Jacob Talmon, Murray Rothbard, and Nicolás Gómez Dávila – on a nearly-empty sound-stage for seven hours with the camera constant for dozens of minutes, Hans-Jürgen Syberberg, cinema’s closest equivalent to such difficult modernist artists as Alban Berg, Karlheinz Stockhausen, T.S. Eliot, Elfriede Jelinek, James Joyce, Thomas Pynchon, and William Faulkner, build his masterpieces on citations from Albrecht Dürer [10], Thomas Mann [11], and Richard Wagner [12].

25. Zenza Raggi, Carsten Frank, Janette Weller, Bianca Schneider, Patrizia Johann, Peter Martell, and Margarethe von Stern in Marian Dora Botulino’s Melancholie der Engel (2009), Reise nach Agatis (2010), and Debris documentar (2012)

I had a dream, which was not all a dream. / The bright sun was extinguish’d, and the stars / Did wander darkling in the eternal space, / Rayless, and pathless, and the icy earth / Swung blind and blackening in the moonless air; / Morn came and went—and came, and brought no day, / And men forgot their passions in the dread / Of this their desolation; and all hearts / Were chill’d into a selfish prayer for light: (Lord Byron, “Darkness,” 1816) [13]

Niedersinkt des Tages goldner Wagen, / Und die Stille Nacht schwebt leis’ herauf, / Stillt mit sanfter Hand des Herzens Klagen, / Bringt uns Ruh’ im schweren Lebenslauf. (Karl Georg Büchner, »Die Nacht,« 1828) [14]

Alles Vergängliche / Ist nur ein Gleichnis; / Das Unzulängliche, / Hier wird’s Ereignis; / Das Unbeschreibliche, / Hier ist’s getan; / Das Ewig-Weibliche / Zieht uns hinan. (Johann Wolfgang von Goethe, Faust, 1832) [15]

Laß, o Welt, o laß mich sein! / Locket nicht mit Liebesgaben, / Laßt dies Herz alleine haben / Seine Wonne, seine Pein! / Was ich traure weiß ich nicht, / Es ein unbekanntes Wehe; / Immerdar durch Tränen sehe / Ich der Sonne liebes Licht. / Oft bin ich mir kaum bewußt, / Und die helle Freude zücket / Durch die Schwere, so mich drücket / Wonniglich in meiner Brust. / Laß, o Welt, o laß mich sein! / Locket nicht mit Liebesgaben, / Laßt dies Herz alleine haben / Seine Wonne, seine Pein! (Eduard Friedrich Mörike, »Verborgenheit,« 1832)

Am Waldsaum kann ich lange Nachmittage, / Dem Kuckuck horchend, in dem Grase liegen; / Er scheint das Tal gemächlich einzuwiegen / Im friedevollen Gleichklang seiner Klage. / Da ist mir wohl, und meine schlimmste Plage, / Den Fratzen der Gesellschaft mich zu fügen, / Hier wird sie mich doch endlich nicht bekriegen, / Wo ich auf eigne Weise mich behage. / Und wenn die feinen Leute nur erst dächten, / Wie schön Poeten ihre Zeit verschwenden, / Sie würden mich zuletzt noch gar beneiden. / Denn des Sonetts gedrängte Kränze flechten / Sich wie von selber unter meinen Händen, / Indes die Augen in der Ferne weiden. (Idem., »Verborgenheit,« 1838) [16]

Wer, wenn ich schriee, hörte mich denn aus der Engel Ordnungen? (René Karl Wilhelm Johann Josef Maria Rilke, Duineser Elegien, 1912) [17]

Note: All the sources of citations in this article can be found in this page.

Author Bio: Mr. Gal Ben-Kochav, B.A., M.A., received his B.A. (2013) and M.A. (2016) in Sociology and Anthropology from the School of Social and Policy Studies, Gershon H. Gordon Faculty of Social Sciences, Tel Aviv University. He spent the last couple of years writing a (yet-unpublished) draft of a lengthy scholarly monograph, in Hebrew, dealing with the application of evolutionary psychological theory in the study of social (ethnic- and sex-based) stratification and structure in Israel, currently standing at 1,086 single-spaced pages in Times New Roman standardized at a font of 12. He has long been interested in art, avant-garde/experimental, and independent cinema.