6. Mania Akbari and Amin Maher in Abbas Kiarostami’s 10 (2002) and 10 on Ten (2004)

Abbas Kiarostami did something similar to what Costa did as discussed in the above entry by forgoing both “plot” and decoder-ring semiotic symbolizations-“pure cinema” auteurism/formalism as substitute for emotion. He simply attached two small digital cameras into the dashboard of a car and asked a mother and her son to drive around Tehran while reenacting scenes from their lives as the whole thing is filmed merely from two angles.

This “uncinematic-merely-filmed-literature-and-theatre” is one of the most emotionally-profound and truth-based learning-experience in the entire history of cinema. Readers are strongly encouraged to also watch the brilliant documentary companion piece 10 on Ten made two years later (which only has 470 votes on IMDb!) in order to watch Kiarostami drive his own car, critiquing the ridiculousness and over-simplicity of the entire Hollywood “cinematic language, gaze, expression, and devices” edifice with its arrival at emotional states after decoding camera movements within two seconds without learning anything valuable or interesting about life (or indeed about anything but cameras), explaining the obvious superiority of his method of working with actors with the intention of getting amazing body-, face-, emotion-, feeling-, psychology-, voice-, dialogue-, and tone-based performances out of them, naturally, a much more enriching and rewarding approach from the point-of-view of any viewer treating cinema as a way to learn about and improve their lives perceptually-perceptively rather than as an algebraic exercise game.

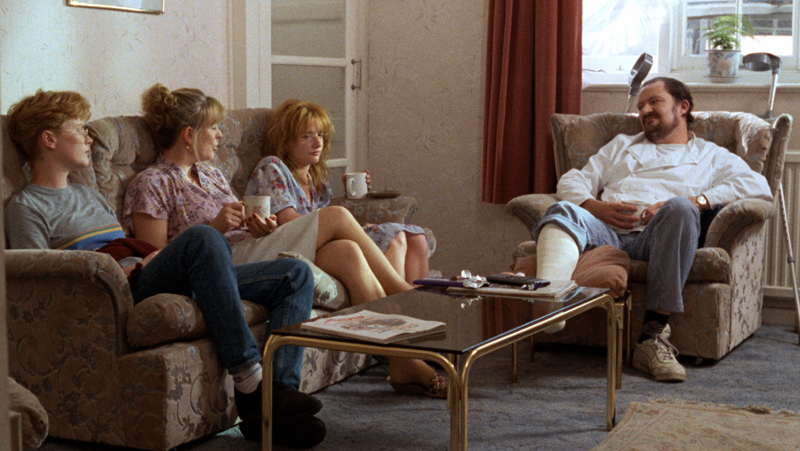

7. Alison Steadman, Jim Broadbent, Timothy Spall, Claire Skinner, Jane Horrocks, Stephen Rea, and David Thewlis in Mike Leigh’s Life Is Sweet (1990)

Similar to The Wife discussed above in being an ensemble-based film forgoing plots, anti-multivalent artificial point-of-view highlighting of one actor/character over the other, and “cinematic language” substituting acting and emotions for understanding characters via instantly-decodable camera positions/angles, Mike Leigh’s masterpiece highlights the emotional immaturity of adolescent rebelliousness masquerading as “change-the-world” politics and social consciousness.

Carney also convincingly argues that the film is one of the most subtle and humorous critiques of said Hollywood filmmaking techniques ever: “The decorations in the Regret Rien present a parable about the difference between superficial and deep meaning-making–in life and art. Like [Hollywood films] (or the critic or viewer who gratefully decodes the meanings they offer), Aubrey thinks that you create significance simply by putting something in a frame and spotlighting it[, Aubrey] hangs up a bird cage to indicate ‘the Sparrow,’ a cat to indicate ‘the street,’ a gas mask to indicate ‘the war,’ an accordion to indicate ‘the music of Paree’ and he thinks he‘s created those meanings[, it is] the semantic equivalent of a heat-and-eat meal: instant, effortless, and ultimately insubstantial[, i]t takes no time or commitment on the part of the artist to create, and no energy or involvement on the part of the viewer to consume (which is why it results in no growth or nourishment). Aubrey has not learned the lesson the film he is in teaches–that meaning (the meaning of a life, a family, a place, a relationship with another human being) can only be created with time, effort, care, sensitivity, and beat-by-beat responsiveness. Meaning must be made, it cannot simply be indicated [which] is why the meanings in Leigh’s work are so different from and take so much more than effort to comprehend than the metaphors and symbols in [Hollywood] [which are] [i]nstantaneous (like Aubrey‘s cat and accordion set decorations, you simply ‘see’ the meaning and it exists), the practical, social truths of Leigh’s works are a product of work and duration [for t]hey take time and effort to make in the first place and they keep changing from second to second [as t]hey take time and work for a viewer to apprehend and time to keep up with. [Leigh‘s k]nowledge is slow and arduous. It’s not something you suddenly ‘get’ (as in visionary film), but something that is gradually and progressively achieved[,] [Aubrey’s] notion of set decoration [is] the insistently metaphoric methods of most American films [that] elevate the truth of ideas over the truth of experiences [rendered] in a kind of intellectual shorthand in which ‘this means that’ in a strictly intellectual way [so for example a] sled means a lost childhood; a cavernous livingroom means loneliness; ominous music and shadowy lighting mean spiritual emptiness and nostalgia. Leigh is committed to a more spatially involved and temporally extended sense of truth [which] is not the product of a viewer’s or a character’s mental relation to a series of sounds and images (the heart of the metaphoric-symbolic method), but is the result of the viewer‘s and character’s complex, gradual process of interacting with a series of people and events extended across space and time. Leigh’s characters do not interact in term of glances, and his viewers cannot take in his meanings at a glance [and] meanings must be lived through and lived into.”

8. Маргарита Терехова, Олег Янковский, Николай Гринько, and Анатолий Солоницын in Андрей Тарковский’s Зеркало (1975)

“[Тарковский] was the first filmmaker who showed me [changing] ideas or philosophy touches only a superficial aspect of our being, [he changed] how we see and hear [and altered] our experience of time and space–deepening, intensifying, slowing our perceptions down. [Тарковский] gets us hearing dog frequencies [like] a drug experience, but more interesting because it’s not a momentary escape from reality but a whole way of life,” wrote Carney.

Watching this film, the most profound masterpiece from one of the greatest of all filmmakers, and paying attention step-by-step within-the-flow only to bodies, dialogue, faces, emotions, vocal/verbal tones and turns, feelings, psychology, etc., while ignoring the nurtured urged to try to pin and pigeonhole it all down to some grand theme symbolically-metaphorically or to interpret it via “cinematic language” that will not make its difference from spoon-feeding instant Hollywood cinema apparent, is like living the entire range of life’s emotions – family, love, growing-up, happiness, loneliness, depression, death, adolescence – in 106 minutes as if in an out-of-body spiritual cleansing experience which truly stands together as a work of art with the greatest of operas, poems, and paintings. Those who did not manage to snatch the Kino Video DVD will be pleased to know it is available legally on YouTube.

9-10. Catherine Breillat’s Romance X (1999, for Caroline Ducey) and À ma sœur! (2001, for Anaïs Reboux and Roxane Mesquida)

Two of the most profound and emotionally-truthful films ever made about the battle of the sexes and the differences between the sexes (regarding sexuality and love as well as other things), the former about (unsimulated!) sexual sadism and the latter about what critic Ginette Vincendeau accurately described, discussing the film’s treatment of the differences between two sisters, one romantically-naïve and the other more emotionally-wise, in her Criterion DVD insert as “deadpan comments about sex, love, and virginity balanc[ing] Elena’s naïve romanticism [like] her stated wish to divorce sex from love (‘Personally, I want my first time to be with a boy I don’t love’)[,] [Breillat’s] excruciating portrayal of adolescent sex is accompanied by a merciless critique of male romantic discourse and machismo[,] [Fernando’s] single-minded pursuit of vaginal penetration is conducted through sugary Latin-lover babble (as in ‘That would be a proof of love’)[,] [t]he younger but wiser Anaïs and the audience watch as Elena falls for this hackneyed male flattery, just as she later buys his offer of an engagement ring.”

11-14. Lars von Trier’s Breaking the Waves (1996, for Emily Watson, Stellan Skarsgård, and Katrin Cartlidge), Idioterne (1998, for Bodil Jørgensen, Jens Albinus, Anne Louise Hassing, Troels Lyby, Nikolaj Lie Kaas, Louise Mieritz, Henrik Prip, and Paprika Steen), Dogville (2003, for Nicole Kidman, Paul Bettany, Ben Gazzara, James Caan, Patricia Clarkson, and Philip Baker Hall), Manderlay (2005, for Bryce Dallas Howard, Willem Dafoe, Danny Glover, Željko Ivanek, and Chloë Sevigny), and Antichrist (2009, for Charlotte Gainsbourg)

I have been told by very angry dudebros whose idea of great cinema is never-ending explosionfests that I “cannot possibly be an actual cinephile” because what I find interesting in cinema is acting, dialogue, emotions, psychology, human interactions, ways to improve, understand, and enrich life, etc. rather than decoder-ring shortcuts to understand characters’s emotional states and one’s reaction to them easily-understandable within one second, simplistic-generic messages decodable by deconstructing visual metaphors and camera movements, and other sorts of visual gaudiness. At best I was a connoisseur of that lowly and inferior “mere literature” (said dudebros insisted cinema has nothing to learn from).

The difference between filming an actor in a large house and thereby instantly-signaling-visually to the viewer that they are lonely and perceptually/perceptively studying their depression through body and face and allowing the viewer to improve their understanding of fellow humans henceforth is the difference between Hollywood/IMDb’s “greatest films” and Lars von Trier’s acting-, body-, face-, emotion-, and tone-based life-changing “cinematic language”/visual-shortcuts-to-understanding-eschewing art cinema. He does all that plus presenting the greatest challenge cinema has ever offered to the bourgeoisie/middle-class politically-correct “social justice” intellectual ideology of flushing universal morality down the toilet and excusing the most inexcusable behavior in the case of “victims.”

At the end of the day, dudebros become exceedingly angry at the very thought of art cinema – with some even claiming they are a dispossessed minority and that too many art films and not enough explosionfests are being made – because, notwithstanding all claims that art is merely anything one claims it is and all taste is subjective, they remind them that they remain mere dudebros rather than philosopher-intellectuals and that it is not possible to eat the cake and have it still, namely, to be interested in nothing but all-style-no-content (many formalist/auteurist journalists use sentences like “he-is-only-interested-in-content-and-not-in-form” as if they were curse-words!) explosionfests with decoder-ring messages specifically-tuned-to-teenage-boys’s-visual-“look-how-intellectual-and-unsentimental-I-am”-self-view-as-intellectuals-solving-riddles-and-breaking-the-code technically/visually-fetishizing and emotionally-uninterested psychology one instantly deconstructs and shortcuts to emotional situations one understand within a second and gain cultural/symbolic capital.