One of the great tricks of cinema is making the impossible seem not only possible, but effortless and incidental, “as if by magic.” Little do we know, as average movie goers, what great toils and sacrifices go into the production of a given film.

Whether it’s a big-budget adventure film like The Lord of the Rings or a small independent feature like Annie Hall, the tale of how the film traveled from idea to script to shooting and finally onto the silver screen remains, more often than not, a mystery. Every once in a while, however, a film experiences such hardship, difficulty, or even just enough bad press to overshadow the move entirely.

The films mentioned below have this feature in common. Some are undeniable classics, fated to stand the test of time and live forever in cinematic glory. Others were unfairly maligned, enduring scathing reviews and terrible box office to eventually become a cult classic or undergo a reappraisal of their worth. And some, for better or worse, never managed to step out of the shadow of their arduous productions. Here are the Top 10 Most Insane Productions of all time.

1. The Wizard of Oz (Victor Fleming, King Vidor, George Cukor & Norman Taurog, 1939)

Few movies in the history of cinema are as well-known and beloved as The Wizard of Oz. Nearly eight decades after it first premiered at Grauman’s Chinese Theatre it remains as vivid and entertaining as the day it was released. Which makes it all the more surprising that as well known as the film is, the messy and disastrous details of the film’s production remain largely unknown by the general public.

The film was originally set to be directed by Norman Taurog, who was replaced by Richard Thorpe after filming several Technicolor tests. Thorpe, in the meantime, shot about 2 weeks worth of footage before being replaced — including the only known footage of Buddy Ebsen as the Tin Man.

Ebsen suffered a severe allergic reaction to the aluminum powder used for his makeup and was hastily replaced with Jack Haley, who reportedly assumed Ebsen had simply been fired.

Studio heads, meanwhile, feeling Thorpe was pushing the production too fast, had him replaced with George Cukor, who removed the blonde wig Judy Garland had been instructed to wear and told her to “be herself” — even at the cost of reshooting all scenes showing her in the wig.

It wasn’t long before Cukor – already scheduled to work on Gone with the Wind – was in time replaced by Victor Fleming (who would himself win an Oscar for directing the same film), who adhered to the creative direction Cukor had steered the film in and wound up shooting the majority of the film as we know it today.

Although production had become more stable under his watch, it was not without its challenges. Margaret Hamilton (the Wicked Witch of the West) was severely burned during her dramatic appearance in Munchkinland, and Ray Bolger testified that the “frightening” costumes prohibited them from eating with other actors in the studio commissary.

To top it all off, Fleming would himself leave the production, leaving the sepia-toned Kansas sequences to be filmed by King Vidor, including the film’s most famous musical sequence, “Over the Rainbow.”

Upon its release, The Wizard of Oz was met with critical and commercial acclaim and has since entered the pantheon of all-time great films. Troubled though its production may have been, its charm, magic, and timeless message of coming home have resonated with children across the world and will for many years to come.

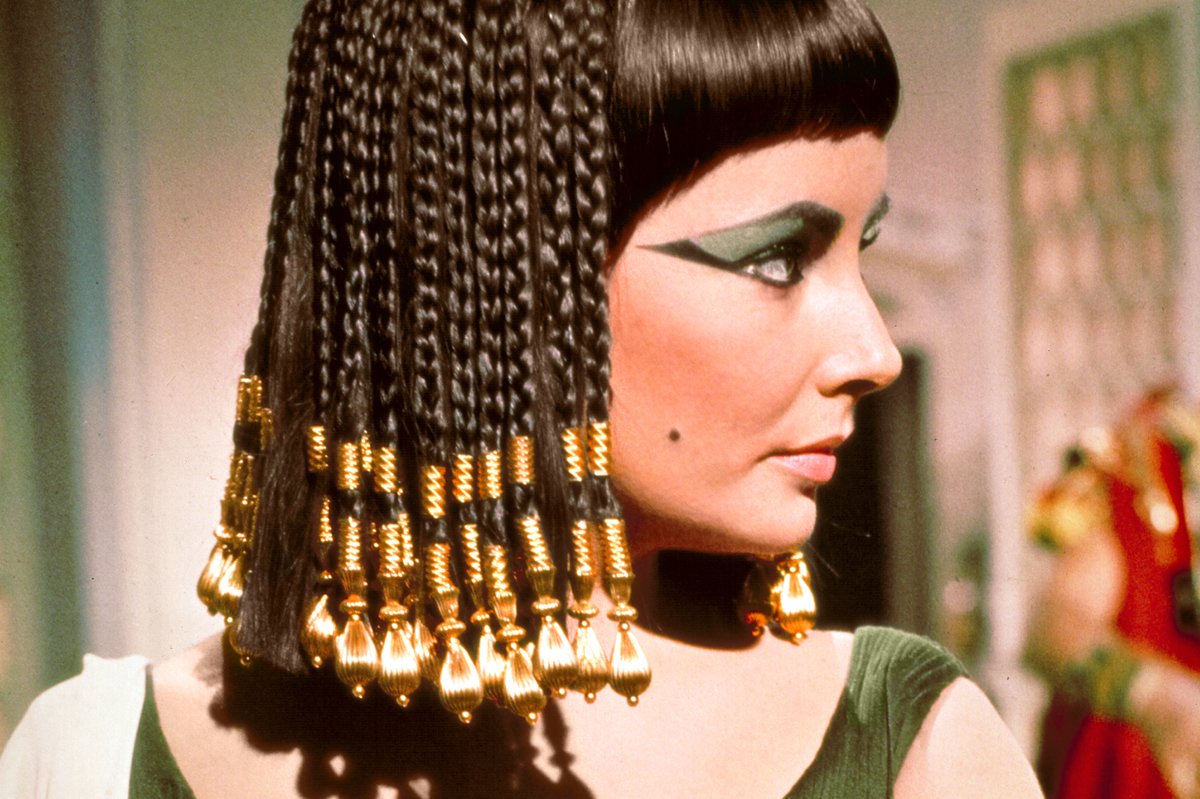

2. Cleopatra (Joseph L. Mankiewicz, 1963)

Lavish historical epics used to be all the rage in the Golden Age of Hollywood. Films like The 10 Commandments, Ben-Hur, and Gone With the Wind used to be as common a sight on the silver screen as the superhero films of today. Trends, however, tend to fizzle out as quickly as they appeared, and in the case of Joseph L. Mankiewicz’s Cleopatra, they occasionally grind to a screeching halt.

The film was originally set to be produced by Walter Wanger, who envisioned a much more lavish production than the $2 million project 20th Century Fox had in mind. Wanger successfully negotiated a higher budget of $5 million and production began in 1961, but after 16 weeks Elizabeth Taylor became ill, which shut down work on the film for several weeks.

When the studio heads discovered that only 10 minutes of film had been shot, director Rouben Mamoulian was fired and replaced with Joseph L. Mankiewicz. Once filming started again, actors Peter Finch and Stephen Boyd were replaced with Rex Harrison and Richard Burton, requiring their scenes to be filmed again.

The film attracted further notoriety once word of Taylor and Burton’s affair became known to the media. Additionally, Mankiewicz was fired once the film finished principal production and went into editing, but was eventually rehired to reshoot the film’s opening battle sequences.

All in all, Cleopatra wound up costing $31 million — a record sum in its day — and was met with lukewarm reception upon its premiere at Cannes in 1963. Though the film attracted praise for its sumptuous visuals and set design, its length, enormous production costs (it almost bankrupted Fox) and Taylor and Burton’s highly publicized affair overshadowed its other merits.

To this day, although the film has undergone a reappraisal in recent years, Cleopatra might be best known for Elizabeth Taylor’s 65 costume changes — a feat that landed her in the Guinness Book of World Records.

3. Jaws (Steven Spielberg, 1975)

In many ways we are still living in the world shaped by Jaws. Although there had been box office hits before, nothing really matched up with the unprecedented success of the maritime thriller in the summer of 1975.

Of course, the filmmakers didn’t know that at the time: in fact, given the difficult circumstances and logistics of the shoot, most of them assumed that the film would be an enormous flop and that they (including a then unknown director named Steven Spielberg) would never work again.

To begin with, shooting at sea proved much more difficult than the crew anticipated. Martha’s Vineyard had been chosen for shooting partly because its sea bottom barely dropped below 35 feet for 12 miles away from shore (making shooting and using the giant mechanical sharks that give the film its name easier): however, Spielberg had not anticipated the difficulties inherent to shooting on open water.

Weather changed at the drop of a hat (leading to different lighting and colors from shot to shot), unwanted boats would drift in and out of frame, and during the shoot of the climatic final scene the boat began to sink for real. Additionally, the shark didn’t work.

The robot (fondly known to cast and crew as “Bruce” after Spielberg’s lawyer) was prone to failure, leading Spielberg to shift the shooting schedule to accommodate the repairs needed. However, he soon found himself needing to change his approach entirely, eliminating the shark from the first half of the film.

The film’s shoot went 3 times longer than intended, going way over budget from $4 million to $9 million…with $3 million alone being dedicated to getting the sharks to work.

Despite the enormous setbacks, the film is that much better for it, The shark’s absence from the majority of the film prompted Spielberg to be creative in his approach, creating an atmosphere of suspense and dread that could not have been accomplished had the shark been visible in the opening scene.

Audiences seemed to agree: Jaws became the highest grossing film of all time, with $470 million being the final box office tally, and inspired a generation of moviegoers afraid to set foot in the water.

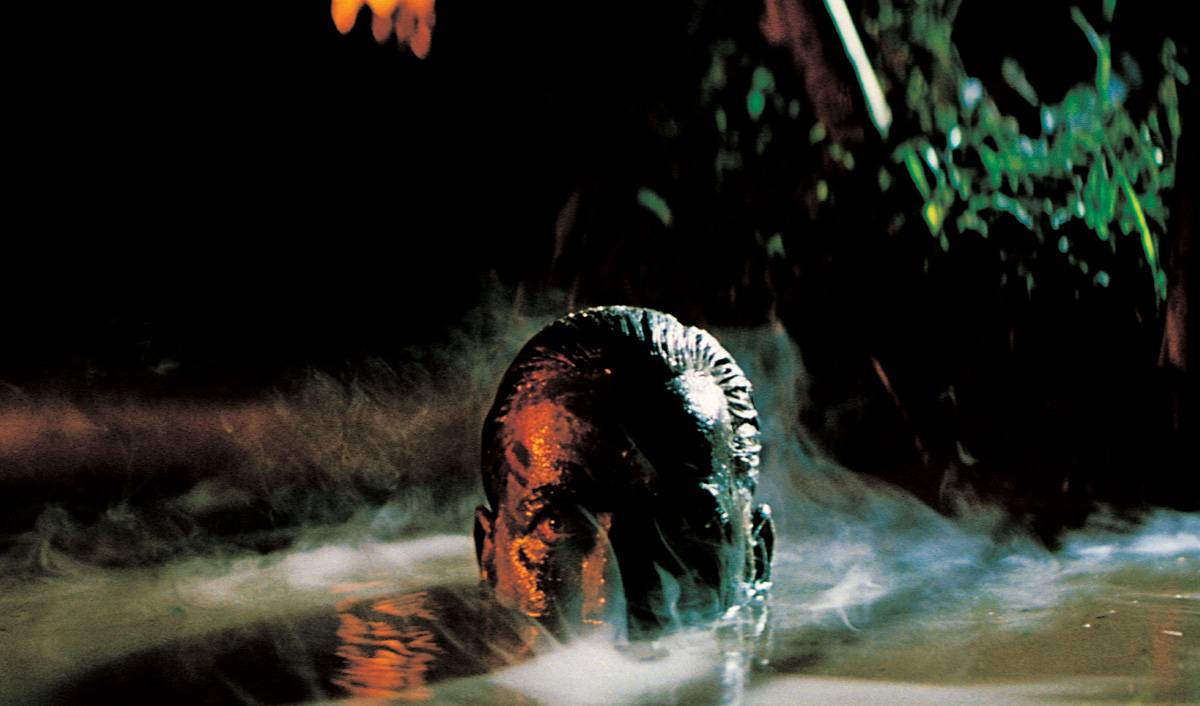

4. Apocalypse Now (Francis Ford Coppola, 1979)

No director looms over a specific decade of filmmaking the way Francis Ford Coppola looms over the 1970s. If he had only made the first two Godfather films and The Conversation, he would still be recognized as a very talented filmmaker. He ended the decade with Apocalypse Now, a kaleidoscopic nightmare of war and destruction which cemented his reputation as a master of his craft and one of the most influential figures of his generation. But this success came at a price.

Production on Apocalypse Now began in the spring of 1976, and almost immediately ran into trouble. Two weeks into filming, Coppola fired leading man Harvey Keitel and replaced him with Martin Sheen, who would later suffer a heart attack due to the strains of production. Millions of feet of film were shot as Coppola wrote and rewrote sequences, and what was originally slated to be a 14 week production ballooned to 14 months.

To make matters worse, Marlon Brando arrived on set for his role as renegade military commander Kurtz grossly overweight and without his lines, forcing Coppola to dress him in black and shoot him in the shadows. On no less than three occasions during production did Coppola threaten to kill himself.

When an unfinished cut of the film finally premiered at the Cannes Film Festival in 1979, it was received with overwhelming praise and was awarded the Palme D’Or. Alas, the film seemed to take its toll on Coppola: once lauded as the poster boy for the New Hollywood era of filmmakers, the director continued to make films, but never again with the same amount of critical or commercial success as his output in the ‘70s.

5. Heaven’s Gate (Michael Cimino, 1980)

Heaven’s Gate is often remembered today as the film that brought the artistic and innovative filmmaking of the 1970s to a grinding halt. Upon its release in 1980, the film — already infamous for its overlong production — was lambasted for its length, its director’s indulgence, and its unqualified failure at the box office. But it wasn’t always destined to be a failure.

In 1979, director Michael Cimino was on top of the world. His film The Deer Hunter had just won 5 Oscars (including Best Director and Best Picture for himself) and he could make any project he wanted. He decided on a historical treatment of the Johnson County Wars of the 19th century, pitting landowners and settlers against each other in the as-yet untamed American frontier.

Although United Artists wanted the film delivered by Christmas of 1979, Cimino pushed for a contract that not only allowed him more time to do what he wanted, but would ultimately exonerate him if the film went over budget. The film immediately started off on the wrong foot, quickly going over budget and over schedule, with the cast taking 6 weeks to learn how to roller skate and the crew once waiting hours for a particular kind of cloud to appear.

Cimino had apparently let his success go to his head, ordering no less than 32 takes for some shots and taking time to arrange every single extra in just the right way. He even allowed a horse to be blown up with dynamite for one scene.

When the film was finally released in November of 1980, it was an enormous critical and commercial flop. United Artists, founded in 1919, destroyed its reputation in Hollywood with this film, and was sold to MGM the following year.

Likewise, Cimino, once the talk of the town, was ostracized and never made a successful film again. But perhaps the most damaging aspect of Heaven’s Gate was that it put an end to the period of boundless creativity of American filmmaking that was the New Hollywood period.