Somewhere in the hustling streets of Paris, in the retro cafés, or behind the penetrable walls of a modern era’s stylish yet melancholic apartments, a radical film movement found the proper soil and materials to build a brand new, epochal but still prophetic landmark of a fresh cultural and sociopolitical consciousness. Conjured by artists who were related to the legendary French film magazine “Cahiers du cinema,” the beautiful, revolutionary, and at once classic “Nouvelle Vague” hastily came to change cinema forever.

The movement’s novelty lies on many levels, from the script symbology to the cinematography techniques, and from the characters’ profiling to its emerging ideas. Hence, the French New Wave is a timeless symbol of a visual and contextual cinematic breakthrough, projecting feelings and thoughts held in contempt. In its delirious narrative and unforeseen jump-cuts, Jean-Luc Godard’s cinema intersects with François Truffaut’s left-bank style, defining a locus of aesthetic and idealistic monuments.

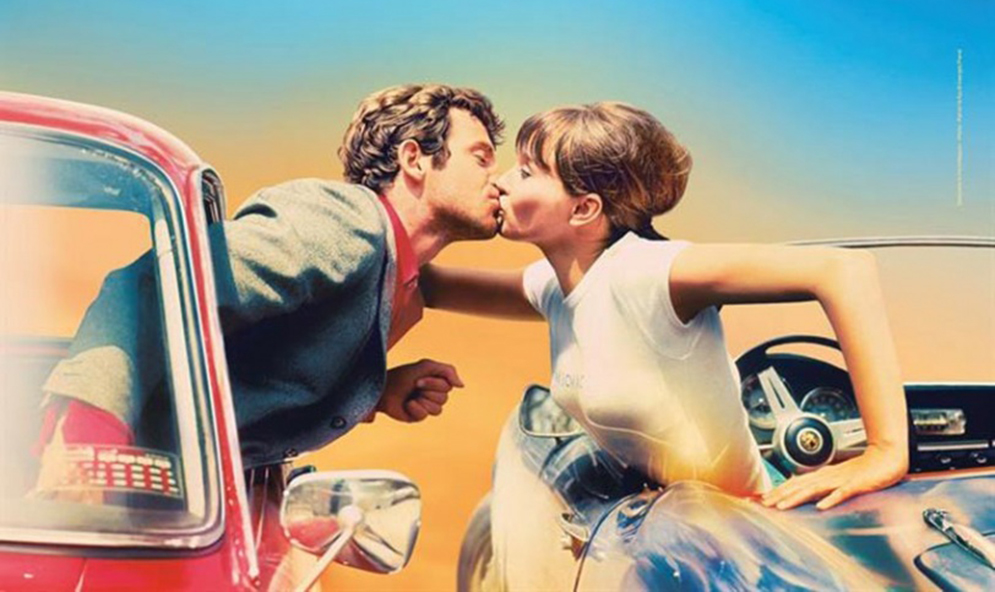

All of the French New Wave fans around the globe distinguish several iconic films, characters, and moments in the countless black-and-white frames of Paris, or in the colorful meanderings of Anna Karina and Brigitte Bardot. If you are one of them, perhaps you’ll detect the poster you have over your bed in this list.

10. Claire’s Knee (1970): On the Wooden Ladder

Encountering with its main characters during their holidays while they’re exempted from routine and responsibilities, this story dives into the calmly aching turmoil of desire that follows Éric Rohmer’s “Le genou de Claire.” As is common in Rohmer’s works, the minimalist plot mainly hovers over the protagonists’ interactions and personal concerns, avoiding suspense but offering many iconic moments of primal inner electricity.

Ostensibly confident, experienced, and emotionally settled, Jerome would sorely question his solid choices during his stay at an idyllic resort, interacting with a provocative female friend and two teenage girls who seem to represent the two opposing poles of the coming-of-age consciousness.

After the incitement of Aurora, who’s an intelligent and maverick writer, the middle-aged man decides to flirt with Laura, an intelligent adolescent of great self-aware and advanced observation. Laura, in her pragmatic charm, doesn’t threaten Jerome’s certitude. But a vigilant part of him is instantly stirred when he meets the gorgeous, innocently playful, and inaccessible Claire.

Springily and ceaselessly, his lust is concentrated on Claire’s knee. As she climbs up a ladder in order to collect some summer fruits, Jerome’s sensuality is triggered in a clear and genuine way. He may be in love, but this young woman’s allure can’t be ignored. “I don’t really want her, but she belongs to me more than to anyone else through my desire,” he claims. These bold words, standing out in a sequence of sincere and insightful dialogues, are divinely reflected on Jerome’s brief moment next to that ladder.

9. My Life to Live (1962): Nana is crying in the cinema

It’s simply Anna Karina’s face that captures everything: the profane beauty, the soul, and the drama. In “Vivre Sa Vie,” one of Jean-Luc Godard’s most beautiful and dramatic works, she embodies Nana: a deeply tragic heroine who is lost somewhere in the unease of her aspirations, and found somewhere in the dirty pavements of Paris during the ‘60s.

In a series of 12 episodes, Nana starts as a hopeful actress. She’s poor and socially insignificant in a demanding city, but her beauty and youth motivate her to chase an unattainable dream. Over time, Nana’s impetuous and desperate choices reveal her dream’s wreckage and her life’s disheartening downfall. As she spends her body, she fails to obtain the fruit of a labored harvest, bearing a course of vain self-sacrifice and torturing excoriation.

Godard films Paris in an astonishing black-and-white retro style, and creates artistic close-ups and unconventionally framed stills. The film’s imagery is unforgettable. But Karina’s scene in the cinema will arguably haunt you forever. As she’s watching the 1928 film “La passion de Jeanne d’Arc,” Nana effortlessly empathizes with this legendary tragic figure. Perceiving herself as a modern Jeanne d’Arc, her lovable face bursts into tears.

8. Last Year at Marienbad (1961): Watching the château’s yard

One of the most debated, analyzed, and divisive pieces of the French New Wave, Alain Resnais’s study on the quintessence of eroticism has nothing to do with interpretations and storylines. At first glance, perhaps the picture’s deliberate vagueness and haywire qualities may generate a sense of disarray. But an unrestrained infiltration into the solid, character-driven semantic sphere of “Last Year at Marienbad” provides plenty of food for thought.

In an immense luxurious residence that is geographically obscure and remote, a married woman and an unwed man meet each other exactly one year after their first romantic encounter in this very place. Gracelessly interacting in the pretentious aggregations of their bourgeois cohabitants, the couple’s story emerges and then dissipates into the fog of various indistinct happenings and moods. Terrible incidents may have happened last year. But no one could ever be sure.

On the château’s balcony, the aloof and distrait woman gazes upon the tremendous, full yard of geometric patterns and specified lines. Her lover is unable to decipher her thoughts and intentions. Their relationship is a sightless ghost of emotions and ferocities that wafts above a strict, defined, and thin environment. Indeed, “Last Year at Marienbad” is a riddle. Except, this simplistically haunting scene is its answer and its conceptual core.

7. Contempt (1963): Camille is lying naked on the red couch

A painstaking analysis of a decadent erotic relationship through the eyes of a bewildered, still enamored man, Godard’s stunning and hurtful “Le mépris” hovers over the expandable cognitive chasm between Paul and his endlessly charming yet self-destructive wife, Camille. Depicted through an overpowering dialectic and visual contrast, their estrangement is a sweat ordeal to taste.

Hidden behind her vacant eyes, black glasses, and unapproachable attitude, Camille becomes more than dominant. Her presence’s gravity arises in a tormenting sentimental denial and in the constant exposure of her flawless physical beauty. As she’s constantly moving somewhere around him, there’s always a veritable or glassy wall limiting her hypostasis. Camille’s fragility is Paul’s wound and ceaseless quest. In the end, there’s something impossible for the audience to ignore: this is Brigitte Bardot.

From beginning to end, and from its deepest layer of ideas to the most superficial level of its imagery, this film is iconic. Godard’s handling of color, geometry, and significative characteristics are notable here. Nevertheless, the extensive scene that depicts Camille lying naked, cloaked in the red fabric as if blazing in obscurity, is one of the film’s most beautiful moments, and one of Bardot’s most unforgettable cinematic views.

6. Cleo from 5 to 7 (1962): Cleo is trying on the black hat in the store

Taking action on the vibrant ground of numerous talented male artists, Agnès Varda displayed her own charisma, illuminating frequent female issues through her experienced and insightful conscious canals. Varda’s contribution to the left-bank aspect of cinema has offered many noteworthy films over the years. Still, her both overblown and gritty leading character of the intelligent “Cléo de 5 à 7” is individualistic in the full spectrum of her personal quality.

Cleo is an up-and-coming pop singer in Paris during the ‘60s. Running into a flat perspective of advancement, she’s being consumed in an out-of-focus sense of declination. A medley of desultory demotivating terrors follows her during a whole day, reflected on her extravagant behavior, interactions, and moments of clarity.

Varda delineated Cleo’s exemplary psychological profile and synthesized the film’s settings with captivating artistry and technical dexterity. Her work’s metaphorical composition and behavioral observation reach a very high level of comprehension. In this fashion, Varda’s intentions are epitomized at Cleo’s fixation to wear a heavy black hat. What she can see in the mirror is what she means to see: a weak body covered by a miniature thunderstorm. During this moment, Cleo’s defeatist approach toward life floats on the surface of her ego.