One doesn’t require any rigorous education in the field of cinema or any long-running practice to instinctively appraise the importance of the opening and the closing shot of a film. The first must be a hook that lodges itself deeply into the spectator’s psyche, while the second is very similar to the final note of a musical piece: it is what resonates in the silence that has fallen or, in our case, in the darkness of the theater.

As the last shot of a film may even alter the audience’s understanding of the meaning of the narrative or, more surreptitiously, it can change the dominant emotional state, one can easily imagine that, for any film-maker, either great or insignificant, the last image of his or her last film is equivalent to a man’s final words on his death bed. But the end of a career most often comes unannounced and many times, eminent directors’ final films (and final shots) are nothing more than a scribble compared to the rest of their body of work.

Other times however, these last images somehow succeed in encapsulating not only the entire significance of the given film, but also the essence of their auteur’s vast oeuvre. Here are ten memorable instances of such last shots.

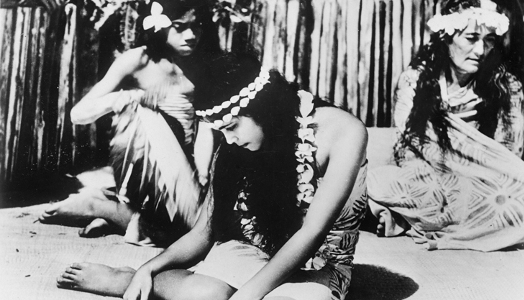

1. Tabu (1931) – dir. F.W. Murnau

German expressionism left an undeniable mark on world cinema and especially on some legendary American genres, the most noteworthy of which is film noir. The ascent of extremism in the wake of Germany’s defeat in the First World War certainly was an important factor in the massive migration of talents to the more clement political climate of America. But beyond the ideological considerations, the United States were starting to clearly delimit themselves from the rest of the world when it came both to building a hyper-efficient business model and to refine a coherent cinematic language.

F.W. Murnau, the creator of such atmospheric gems as Nosferatu the Vampire (1922) and Faust (1926) and who had also applied his incomparable pictorial flair to the story of an ordinary German employee in The Last Laugh (1924), was lured to Hollywood like many others.

There, he produced what is generally recognized as his masterpiece, the soul-stirring Sunrise (1927), but he also went off the beaten track with Tabu, a fiction film that draws its strength from the director’s quasi-ethnological observation of the ancient traditions of the Maori people.

The last shot of the boat that takes away the heroine towards sacrificial death and leaves behind her exhausted young lover not only condensates the director’s romantic pessimism, but also reminds one of the most striking images of Nosferatu: the ones with the ship with the black sails, loaded with its sinister cargo, which floats towards Orlock’s unsuspecting victims.

2. L’Atalante (1934) – dir. Jean Vigo

Jean Vigo is the prototype of a legendary figure in the mythology of cinema, figure who is in fact fairly rare – and fortunately so – : that of the promising young director who, after having made a few remarkable films, is reaped by death, leaving the world to wonder how many more masterpieces he or she could have created.

Many of these shooting stars are relatively unknown to the general public, as it normally takes at least a couple of outstanding films from the same director to secure a firm position in the audience’s memory. But Jean Vigo is an exception: with two documentary shorts (À propos de Nice (1930) and La Natation par Jean Taris (1931)), one medium-length fiction film (Zéro de conduite (1933) and his final feature-length film, L’Atalante, he managed to leave a mark on cinematic game-changers like François Truffaut, who declared that Vigo had shaped the way he looked at things, and Jean-Luc Godard, who dedicated him his film “Les carabiniers”(1963). If À propos de Nice was a staggering debut – a poetic and highly original mixture of the revolutionary spirit inherited from the director’s own father (the anarchist Miguel Almereyda) diluted in a formalist, impressionistic approach , L’Atalante was a grand exit from the scene.

The modest story of the hardships of a young couple quietly living and working on a barge until the heroine flees to see Paris is sublimed by Vigo’s unostentatious lyricism. Even the moments of utter fantasy, like the husband’s vision under the waters of the river, have a matter-of-factness that reaches its peak in the final shot of the film. The bird’s-eye view of the barge which is rapidly being left behind indicates that the couple’s destiny is just a drop in the sea of humanity’s similar preoccupations.

3. Lola Montès (1955) – dir. Max Ophuls

An anecdotic incident from Germany-born director Max Ophuls’ biography sheds an interesting light on his career as a whole but mostly on his last film, the dazzling Lola Montès, and the years that followed its premiere up to his death in 1957.

It is said that when young Maximilian Openheimmer made his debut as a theater actor in 1919, he changed his name to Max Ophuls in order not to embarrass his family in the event that his performance would be a fiasco. Unimportant as this episode may seem, it shows that Ophuls was very self-conscious and was tormented by the eventuality of a failure.

This fear followed Ophuls as he switched from theater to film ten years later, as he became the leading dialog writer of the German studios UFA and afterwards, as his name became synonymous with lavish productions with fluid, hypnotic camera movements which nevertheless always retained a high coefficient of intellectual depth, such as Le Plaisir (1952) or Madame de…(1953).

But it was with his last film, the story of a courtesan’s fall from grace around the middle of the 19th century, that Max Ophuls really tasted the bitter taste of failure, as his film, the most costly ever done in the Old Continent at the time, was not as successful with the general public as estimated and was therefore ruthlessly cut to a much shorter version and to a more conventional chronological order.

The last shot of Lola Montès, which shows a curtain closing on a queue of paying circus patrons who wait for their turn to touch Lola, may be interpreted as a biting irony towards the people who form show business and who are ultimately nothing more than freaks inside the system they have built.

4. Testament of Orpheus (1960) – dir. Jean Cocteau

A poet, a painter, a playwright, a film-maker and a designer, Jean Cocteau was a multi-faceted artist who struggled with reinventing himself after the Second World War, as he was stigmatized by many for allegedly having collaborated with the German invaders (or at least for not having opposed them outwardly enough). But even after the clearing of his name, the accusations being proven wrong, Cocteau was still out of his depth in a time of rapid social and implicitly cultural transformation. His poems did not touch the chord they touched before, or maybe that chord did not exist anymore.

But surprisingly, the old man (he was born in 1889) regained a second youth through his activity as a film-maker. His last film, Testament of Orpheus, was met with very little enthusiasm by both the critics and the general public; however, the “Young Turks” from Cahiers du Cinema, among whom the most ardent was François Truffaut, praised the films and went to see it multiple times in order to grasp its numerous layers of meaning.

Its explanation, or at least its partial disambiguation, lays in the fact that the film was conceived as a magnum opus, as a swan song – Jean Cocteau, unlike many other film-makers from this list, knew that Testament of Orpheus was going to be his final film; after all, he was seventy years old and in poor health.

Therefore, the film is peppered with the more or less prolonged presence of such people as Maria Casares, Jean Marais or Pablo Picasso and, above all, it stars Jean Cocteau playing himself, the one and only Poet who, like Orpheus, makes an incursion in the world of the dead (in Cocteau’s case, in order to better prepare his own).

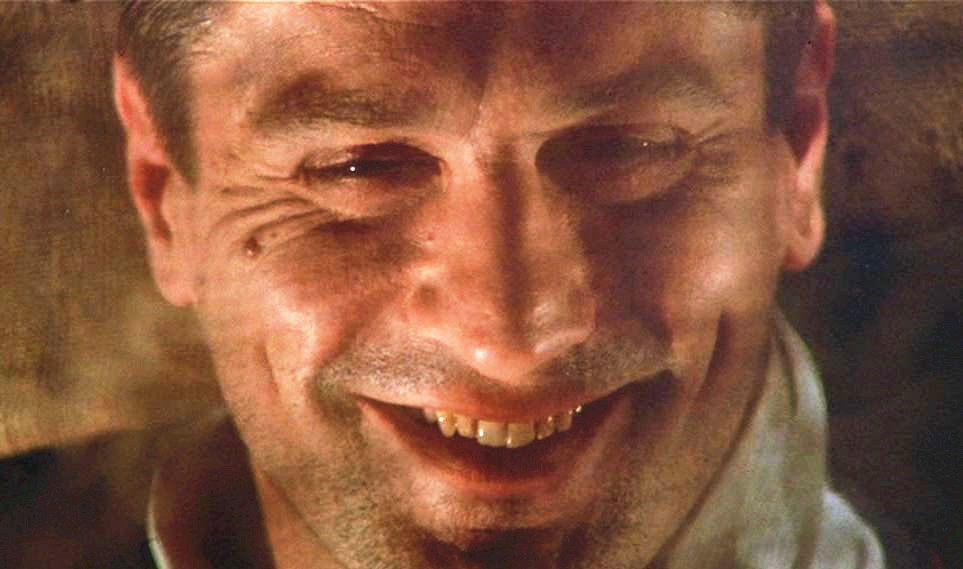

5. The Innocent (1976) – dir. Luchino Visconti

The case of Luchno Visconti was intensely debated by critics – Italian and otherwise – and mostly by those who were strongly politicized. Indeed, Visconti’s social status (he descended from an important aristocratic family) irremediably clashed with his political conviction (he was an extreme leftist). His films, like those of most great artists, are the mirror to a deeply troubled personality, caught into a different “nature versus nurture” type of conflict.

Studying his oeuvre, one can notice that his last film, “The Innocent”, is one of the most direct in its indictment of the uses and customs of nobility. The Chekhovian tenderness towards the destructive lethargy of the people forming this class and the sense of nostalgia that graced Il Gettapardo is gone.

In The Innocent, the protagonist indulges in the physical pleasures his social position offers him without having the moral rectitude or the awe-inspiring solemnity of Burt Lancaster’s character from Visconti’s above-mentioned film. But what the film-maker seems to most firmly condemn is Tulio Hermil’s inability to value human existence at its true price and to show humility in front of the miracle of life – attitude which is in fact neither specifically aristocratic nor communist, but rural.

His ego, his blind pride which were hurt by his wife’s infidelity are nothing but a social construct that lead him to a crapulous murder, which is perpetrated against the most basic notions of human decency in the optics of any social class. The Innocent ends with Tulio’s lover Teresa’s silhouette; no matter the degradation, the ideal of the bearer of life is still present in every woman and Visconti honors that.