There are many sayings that dealing with being at a low point in your life can aspire great creativity, or by oppression comes liberation through the arts, and so forth. This can be made especially for directors away from their traditional means of filmmaking.

Due to a variety of reasons, a director is forced to relocate to another part of the world or find a way to make their films. And out of this struggle, frustration, and a new way of filmmaking, they produced astonishing work that holds up with the very best of their filmographies.

1. From the Life of the Marionettes (1980)

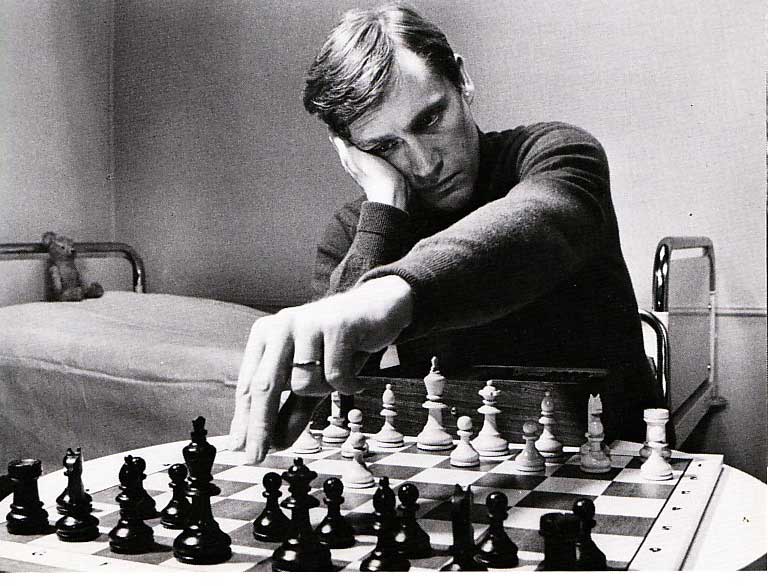

Ingmar Bergman in Germany, on tax exile from native Sweden.

What happened? Ingmar Bergman was arrested in Sweden in 1976 for tax evasion. He suffered a nervous breakdown, was hospitalized, and vowed to never work in Sweden again. He moved to Munich personally and professionally.

Bergman revisited two characters, Peter and Katarina, from the first chapter in “Scenes From a Marriage” for this film. It can be seen as a semi-spiritual sequel to the predecessor. He continued to explore the complexities in a relationship in his fashion.

The film stands out for combining a variety of themes and expressions Bergman has used before. Bergman explores the darkness of a relationship through prostitution, murder, and failed love between two people in a room. He has the precise dialogue between man and woman such as stating the exact number of orgasms she experienced with a man and bluntly stating what they are feeling. He uses a stark black-and-white theatrical setting, still with Sven Nykvist, dream sequences, and even a horror-like element to the relationships explored.

This darkness and at times being difficult to comprehend could only be done away from Bergman’s comfort of Faro. He states it best about his suffering and pain in his exile with, “In ’From the Life of the Marionettes,’ I found a way, a form, a very definite and distinct form to which I could transfer my pain, my anguish and all my difficulties and reshape them into something concrete.” And that he did.

2. Rififi (1955)

Jules Dassin in France, blacklisted from Hollywood

What happened? Like many other great artists in the Hollywood era, Jules Dassin was blacklisted and named a communist. After five years of trying to find work, primarily in Europe and a failed Broadway play, he landed “Rififi” in France.

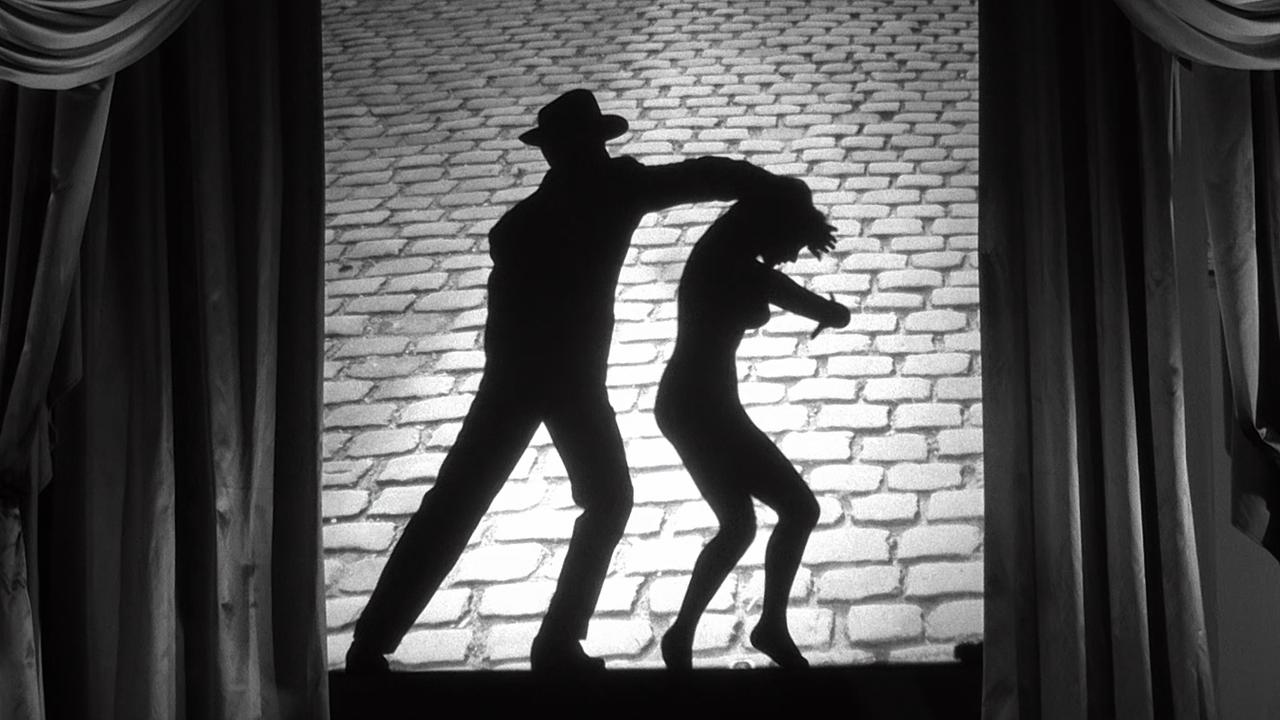

For any fan of a aging criminals looking for their last big heist, or that black-and-white photography from 1950’s French cinema, or that film noir atmosphere, look no further than this film. Despite a low budget, no major starts, and “a bad novel” labeled by Francois Truffaut, Dassin made a masterpiece and was even awarded Best Director at Cannes in 1955.

If you mention this film to anyone, the first thing they will reference is the actual heist scene. Flawlessly executed in form (and in the film) and cinematic terms – no dialogue is spoken amongst the criminals and no musical score. Only the stunning natural sounds, glances between the actors sweating it out (as you are yourself) and perfectly framed shots for 30 minutes.

The plot can fall into that typical three-act structure of setup, execution, and aftermath for those involved, but its the story and the characters that move in this world created by Dassin that keeps you coming back. You could only wish to be as cool as Jean Servais’ Tony the gangster, or sit in the jazz club listening to the song ‘Rififi’. Maybe Dassin related to the character Tony as an aging recently released man from a five-year prison sentence (cough cough) looking for one last score.

Dassin used elements from his previous film noir work like “Brute Force,” “The Naked City” and “Night and the City” to create a stunning cinematic work that stands the test of time, thus showing what a talent the United States casted away.

3. Taxi (2015)

Jafar Panahi in Iran, banned from making films

What happened? After years of legal problem and getting arrested, Panahi was imprisoned by the Iranian government in 2010 and banned from any form of filmmaking for 20 years.

While Panahi was waiting for his testimony, he managed to create “This Is Not a Film” in 2011 and “Closed Curtain” in 2013, exploring in his personal and professional life in one way or another. But with “Taxi” or “Taxi Tehran,” Panahi manages to get back to the root of his filmmaking, creating films grounded in Iranian culture, his love of film, and showing what life is truly like in the capital of the country.

He act as a taxi driver and manages to portray the thoughts and struggles the locals have in the country, from hunger strikes to capital punishment to the film industry. Some even recognized him as the exiled director in his own country. The film shows how Panahi has gotten back to the core of his film and expression, even as a means of therapy out of his frustration and betrayal by his country.

The film received the Golden Bear at Berlin in 2015 where Panahi released a statement before the premiere with, “Nothing can prevent me from making films since when being pushed to the ultimate corners I connect with my inner self and, in such private spaces, despite all limitations, the necessity to create becomes even more of an urge.” Well, Mr. Panahi, you succeeded.

4. Dersu Uzala (1975)

Akira Kurosawa in the USSR due to no support from native Japan and a post-suicide attempt.

What happened? After commercial failures and personal anguish, Kurosawa made his film with support from the USSR.

After a golden period from 1950 to 1965 that is amongst the best in cinema, Kurosawa slowed down a bit. After a failed event with “Tora! Tora! Tora!” in Hollywood, and after a suicide attempt from the commercial failure of “Dodes‘ka-den,” Kurosawa seemed hopeless. It wasn’t until Mosfilm wanted him to bring the story of Dress Uzala to screen, a film in which he wanted to make since the 1930s.

Despite the film being in Russian and featuring no Japanese actors, the film flows with Kurosawa trademarks. Kurosawa always loved nature and all its elements such as the wind, rain, sun, etc. But with this film, he was able to capture all those factors that surrounded the very essence of its main character, Dersu.

The film can be seen as a love letter to nature as we go from snow-covered tundra to a sun-soaked forest. You see the stunning imagery in 70mm and hear those sounds, but it’s the relationship between Dersu and the Captain that strikes our emotions.

The leaving and unification between the two during each respective part is tremendously emotional as you feel like you’ve struggled with these two, like chopping down grass and stems to protect themselves from the cold.

As the film progresses to the end, one cannot marvel how Kurosawa achieved such a breathtaking film with visual imagery and great characters. Maybe Kurosawa felt like Dersu even more because he longed to be in another place, yet never losing his true self.