The Oscar ceremony is less than a month away now and the race is relatively open. Martin McDonagh’s ‘Three Billboards’ won big at the Golden Globes, pushing it to be many people’s favourite to triumph at the Oscars too.

Strong competition comes from auteur Paul Thomas Anderson’s ‘Phantom Thread’ and Jordan Peele’s astonishing debut feature ‘Get Out; it’s a diverse and creative field this year, for which the Academy should be commended.

Despite coming under scrutiny since garnering its recent acclaim, ‘Three Billboards’ should still emerge as the winner of Best Picture on Oscar night: no competing film can match its potent mix of daring, complexity, and audacity.

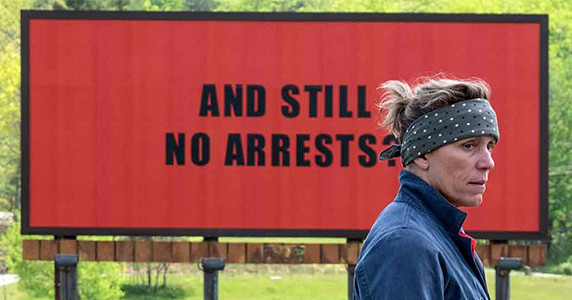

His second feature film set in the U.S.A, ‘Three Billboards’ is a damning, blistering story of justice and morality in small-town America. After her daughter, Angela, is killed, Mildred Hayes (Frances McDormand) puts up 3 roadside billboards reading “Still No Arrests?”, “How Come, Chief Willoughby?”, and “Raped While Dying”.

These, naturally, soon get attention from the people of Ebbing as Mildred seeks some redemption and justice for what happened to her daughter from the policemen who haven’t yet found Angela’s killer. It’s a bold drama, a reflection on America as it is, and it’s a timely piece.

Through its powerful characters and stinging narrative, ‘Three Billboards’ will continue to resonate for a long time after 2017. This list will look at 5 reasons why McDonagh’s film is deserving of winning the Best Picture Oscar when the time finally comes.

1. Frances McDormand’s Central Performance

It appears very likely that Frances McDormand will triumph at this year’s Academy Awards, which would become her 2nd win, her last being for the Coen Brothers’ ‘Fargo’ in 1996.

An interesting circularity can be drawn between the two: her cheerful, Minnesotan cop Marge Gunderson was well-meaning and likeable, coming during a fruitful period in her career, while McDormand’s opposite turn as the angry, fiercely defiant, anti-police Mildred Hayes comes in McDormand’s later years; one cannot help but think that there may be a little of the actor in Hayes, McDormand’s raw and weary riposte in the #MeToo era after decades journeying through the Hollywood system. Indeed, McDonagh wrote the character of Mildred with McDormand precisely in mind.

Like her partnership with her husband Joel Coen that gave birth to ‘Fargo’, McDormand seems comfortable working with McDonagh, a filmmaker with clear parallels to the Coen Brothers in his sharp use of dialogue and black themes.

This is the first substantial role created for a woman in McDonagh’s film career so far and McDormand inhibits it immensely. Mildred reprimands, attacks, and annihilates with her words, delivered in acid tones by McDormand. She spits her dialogue with fire and ferocity but manages to say equally as much in the silences between conversations; McDormand possesses great comic timing and her caustic glances at those around her are able to convey just as much as her words. Her icy stares come from a woman utterly despondent at the world and its ways.

McDonagh said in a recent interview that young girls didn’t have iconic film characters in the mould of James Dean to admire and he may have played his small but significant part in remedying this: in McDormand’s hands, Mildred becomes a John Wayne-like figure, a physically imposing, resilient and unbreakable icon. She’s a character of and for its time, an outpouring of anger in a society full of it.

McDormand’s greatest feat is in pulling all of the contradictions of her character into a believable and empathetic form: Mildred is the anti-heroine we want to be the hero, the deeply flawed person possessed with plentiful humanity.

2. The Rest Of The Ensemble

In his two previous films, McDonagh utilised a trio of main characters, working simultaneously as protagonists and antagonists, and he continues this tradition in ‘Three Billboards’, as McDormand’s Hayes comes up against Woody Harrelson’s Chief Bill Willoughby and Sam Rockwell’s Officer Jason Dixon.

When we first hear mention of Harrelson, it seems as if McDonagh has cast him in a similarly villainous role that the actor played so well in ‘Seven Psychopaths’ (2012), with Chief Willoughby receiving most of Hayes’s fury; narrative proceedings cast him in a fairer light, however, allowing Harrelson to garner sympathy from the viewer.

We see him struggle with his terminal cancer while trying to solve the case of Angela’s murder. It’s a complex role but one mined for bleak comedy by Harrelson. The actor’s scenes opposite McDormand, especially one where he coughs up blood in Mildred’s face in the midst of a heated argument, are some of the most powerful in the film, as the two performers truly match each other and give fully of themselves. This scene also showcases Harrelson’s extraordinary, chameleonic ability to switch between comedy and dark drama at a moment’s notice, just as he did in ‘Seven Psychopaths’ to great effect.

Ebbing is populated by a litany of other notable characters, speaking to the talent of the ensemble to fill their respective roles; in a film that often feels like it could have been presented as a play instead, the acting is paramount to its success. After his breakthrough role in ‘Manchester by the Sea’ (2016), Lucas Hedges makes his character Robbie feel highly believable as Mildred’s son, imbuing him with a clear tension as he tries to fit in at high school when the rest of the town hates his mother.

John Hawkes arrives on screen intermittently as Robbie’s father and Mildred’s ex-husband, convincingly echoing the menace through sneers and outbursts that his character Charlie used to hold over Mildred.

In even smaller roles, Caleb Landry Jones finds surprising depth as the advertisement salesman who puts Mildred’s billboards up; Peter Dinklage mines genuine poignancy as a man called James who’s infatuated with Mildred, despite her prickly demeanour. McDonagh’s dialogue needs people capable of delivering it effectively and the film defers to its actors to do just that.

It’s Sam Rockwell as the divisive Dixon that has received most of the acclaim and rightly so. The actor has been working with McDonagh since appearing in his Broadway play ‘A Behanding in Spokane’ in 2010 and their understanding of each other is concrete: the director expressly wrote this part for Rockwell and he’s perfectly cast, dragging a little empathy out of this odious character that a lesser performer might not have found.

Rockwell spoke of his strong relationship on set with McDonagh, with the director allowing him some leeway to really inhibit his crazy-guy persona and it works, for Rockwell as Dixon becomes every small-town drunk, abusive, idiotic cop with a dangerously inflated sense of self-importance.

Rockwell’s performance is a deftly balanced one, as he dares to make Dixon extremely unlikeable through the film’s beginning before undergoing a remarkable transformation in search of redemption that Rockwell somehow makes the viewer root for.

To do this, he utilises his singular ability to win sympathy in the most disturbing moments – certainly helped by his puppy-dog face – and enlivening his character with the complexity that McDonagh’s writing demanded. It’s a bravura performance, equal to McDormand’s, and should win him the Oscar his long and consistently excellent career deserves.

3. Martin McDonagh’s Screenplay

McDonagh has spoke in the past of his annoyance that theatre isn’t punk enough but he certainly helped to rectify this when he exploded onto the West End scene in the late 1990’s: his plays were a burst of energy in a staid scene and earned him equally as many admirers as detractors.

It was always his ambition to transfer his talents to cinema and, while Three Billboards could have been effective as a piece of theatre, when done right McDonagh’s writing is perhaps the most consistently clever and acerbic in Hollywood outside of the Coen Brothers; a film of theirs like ‘Burn after Reading’ (2008) could easily have been penned by the Irishman, just as ‘Three Billboards’ wouldn’t have surprised many if it had been created by those two.

He’s always written in darkly comic tones, as in the gruesome and existential ‘In Bruges’ (2008), but ‘Three Billboards’ sees him fine-tune his talents and the result is a much more complex and richer work. McDonagh has always had an ear for effective use of profanity and characters do so at will and in hilarious fashion, as when Chief Willoughby swears over the phone in front of his children during their Easter Lunch.

Characters utter inane platitudes like ‘Anger just begets more anger’ and McDonagh is urging us to realise the emptiness of such statements, his dry joke at the expense of those who believe in and use them. His words, through the vessel of McDormand’s Mildred mainly, turn their attention to many vulnerable targets, including a priest for his complicity in covering up child sex abuse in the church and Dixon for his cruel treatment of African-Americans.

In that scene with McDormand and Harrelson facing off, the quick and vulgar dialogue being exchanged is thrilling to witness, a visceral moment that screams from McDonagh’s page. The screenplay’s quality lies in the fine balance measured by McDonagh as it veers between black comedy, stunning violence, and sharp social commentary in the space of minutes.

It’s also incredibly involving, its narrative like a page-turner, and one wouldn’t mind spending more time with Mildred on her revenge mission as the film ends.

4. The Film’s Editing

Between 1981 and 2013 every Best Picture winner had also been nominated for Best Editing and the two are intrinsically linked; good editing inevitably leads to a successful final product. Jon Gregory earned his first Academy Award nomination for his editing work on this film and his touch can be seen throughout ‘Three Billboards’. He worked with McDonagh previously, editing ‘In Bruges’, and they combine to greater success here.

‘Three Billboards’ is a film that relies on key editing, in how it presents its characters and their narrative arcs. This applies most to Rockwell’s Dixon, as the editing is paramount to showcasing his journey to redemption by the film’s end. This is made believable as Dixon’s transformation isn’t overly emphasised and happens slowly from the middle of the film. Gregory understands that life isn’t black and white and doesn’t edit Dixon as such.

His most vital contribution is the placing of the flashback scene showing Mildred’s last conversation with Angela before she was killed: McDonagh had initially put this in at the end of the film but Gregory maintained that this was far too late, moving the scene to earlier in the narrative.

This move enables the viewer to feel sympathy for Mildred at an earlier stage when one could have felt alienated from her for much longer. It makes her acts, like her burning down of the police station, more understandable; the editing highlights the suffering that Mildred has gone through, having an argument with her daughter as the last words she ever spoke to her, and goes a long way to justifying her coming actions. Gregory’s editing, therefore, is responsible for the complexity of both Dixon and Mildred, by making one neither truly horrible and unlikeable.

5. The Moral Ambiguity

The overarching theme of ‘Three Billboards’ is moral ambiguity: McDonagh locates the ‘grey’ area in society, nothing is ‘black and white’ in the film, and it’s the most complex Best Picture nominee because of this. The town of Ebbing is populated by fractured, flawed characters, none explicitly good above all others.

At first, we think Chief Willoughby is to blame for Angela’s murderer not being caught, as his name adorns Mildred’s billboards, but the narrative portrays a decent family man, a beloved husband and father. He’s gruff but fair, rough but kindly, and he’s also dying of terminal cancer.

Mildred finds herself against most of the town who side with the ‘good man’ Willoughby and McDonagh highlights by this fact the total power of narrative when choosing sides: the people of the town put their trust in their Chief of Police as he has the perfect family unit, in opposition to the odd, intense woman who lives on the edge of town, even as she mourns the loss of her murdered child.

Shades of #MeToo are evident here, in the overwhelming pressure to be silent about violence and misconduct, something that’s only regrettably changing now. This small American town may all know that Angela Hayes was raped and murdered, in brutal fashion, but don’t want to rock the boat, disturb the peace. Sexual violence is swept under the carpet and Ebbing can continue life as normal.

McDonagh has always wrote characters of nasty and brutal proportions, wrestling with their humanity and morality. So Mildred is ostensibly the protagonist of the piece but McDonagh makes sure to sully this notion, in his acknowledgement that even those deemed ‘good’ can do wrong. We see Mildred petrol bomb the police station, with Dixon still inside.

In a melancholic scene, she acts unfairly rude to James on their date, despite him being one of the few to sympathise with her plight and reach out to her. A lesser writer would have written one-dimensional villainous policemen and idealised Mildred as a vengeful heroine but McDonagh knows that life just isn’t like this. Each character, clearly, thinks they are right, thinks they know best, but when considered wholly they all occupy wrong a lot of the time.

Dixon undergoes a transformative arc, from being the worst character at the start to finding some form of redemption at its closing. He’s clearly a racist, despicable cop but he loses his title and hands in his badge; he’s a man filled with hate, instilled most likely by his overbearing live-in mom, but he has enough humanity in him to try and find Angela’s killer.

As soon as ‘Three Billboards’ began winning awards, especially its success at the Golden Globes, the backlash was swift and loud. Much of the criticism has targeted Dixon’s character arc, stating that he shouldn’t find redemption considering his torturing of African-Americans, which is briefly touched upon.

He isn’t, however, fully redeemed at any point: Dixon and Mildred are on their way to murder a man for allegedly being a rapist, an act which will in all likelihood lead to their imprisonment; nor does he become a clear hero, as the film contains none, only deeply flawed humans.

Indeed, many have won Best Supporting Actor Oscars for playing monstrous men – Christoph Waltz as Colonel Hans Landa in ‘Inglorious Basterds’ (2009) springs to mind – and Rockwell as Dixon would just represent a more realistic version of this. The audience still knows that he’s a bad person, but McDonagh maintains that there can be ‘greyness’ in everyone.

What binds Dixon and Mildred is their rage, something reflected in American society today and it’s why the film is so prevalent. America right now is morally corrupt, deeply flawed, and surviving in it means sometimes having to enter into this ‘grey’ area. Together, as they exit our screens, they are morally ambiguous monsters, products of their environment and, McDonagh contends, not as different as one would at first think.