Handheld camera didn’t really exist until the late 1950s. Sure, directors like Dziga Vertov or even Abel Gance played around with the technique, but due to the size and weight of camera, focus, tripods, etc, true handheld had to come much later. In the late 1950s, cameras could be picked up, creating a new form of style for documentary filmmaking or cinema verite.

Since cameras could be mobilized, it increased the filmmaker’s choices of shooting whether for creative or productive means. As time continued, it became a sort of down and gritty or realistic style to specific films. However, as cameras continue to get smaller and more mobile, independent filmmakers use handheld because it’s cheap and easy.

Despite the way the handheld camera came about or has been frequently used for productive means, certain films use handheld camerawork to create a world and atmosphere in which the characters inhabit. The camerawork is used in an elegant and sophisticated style that if the camera was stationary or static, the film would lose its energy, tone, detail, and overall style.

Therefore, here are some examples of great handheld camerawork used for the entire film, not just certain segments.

1. Battles Without Honor and Humanity (1973)

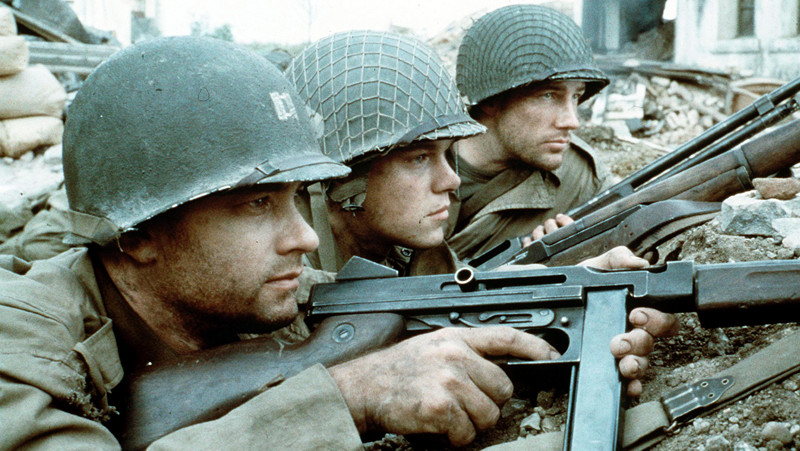

Kinji Fukasaku’s first film out of five, which even sparked another trilogy for the epic yakuza gangster films. Fukasaku wasn’t concerned with creating yakuza films like the intimately designed and paced “The Wolves” by Hideo Gosha, or the crazy, action surrealist films of Seijun Suzuki, or the meticulously framed “Pale Flower” by Masahiro Shinoda. He wanted a shaky camera to capture his characters and their worlds.

The film takes places post-World War II Hiroshima, where corruption breeds amongst the population. We see Bunta Sugawara as Shozo Hirono go from a low-level criminal to yakuza boss. However, Fukasaku moves the film and narrative along so quickly it’s hard to keep up. And he does this to his effect by using a down and dirty approach with the camera. The camera is seen almost like a spectator in the large market crowds.

For example, when one of the many members of the rivaling clans or cops gets shot and a mass panic happens, the camera shakes uncontrollably going up, down, left and right, literally throwing you into post-World War II Japan. The style of the film wouldn’t have worked if the camera was controlled because all the characters are not controlled. It gives you a sense of edge and uncertainty as the film (and series) unfolds.

You never know what’s going to happen or what the characters are going to do. Therefore, the handheld camera work was the perfect way to create this gritty yakuza world.

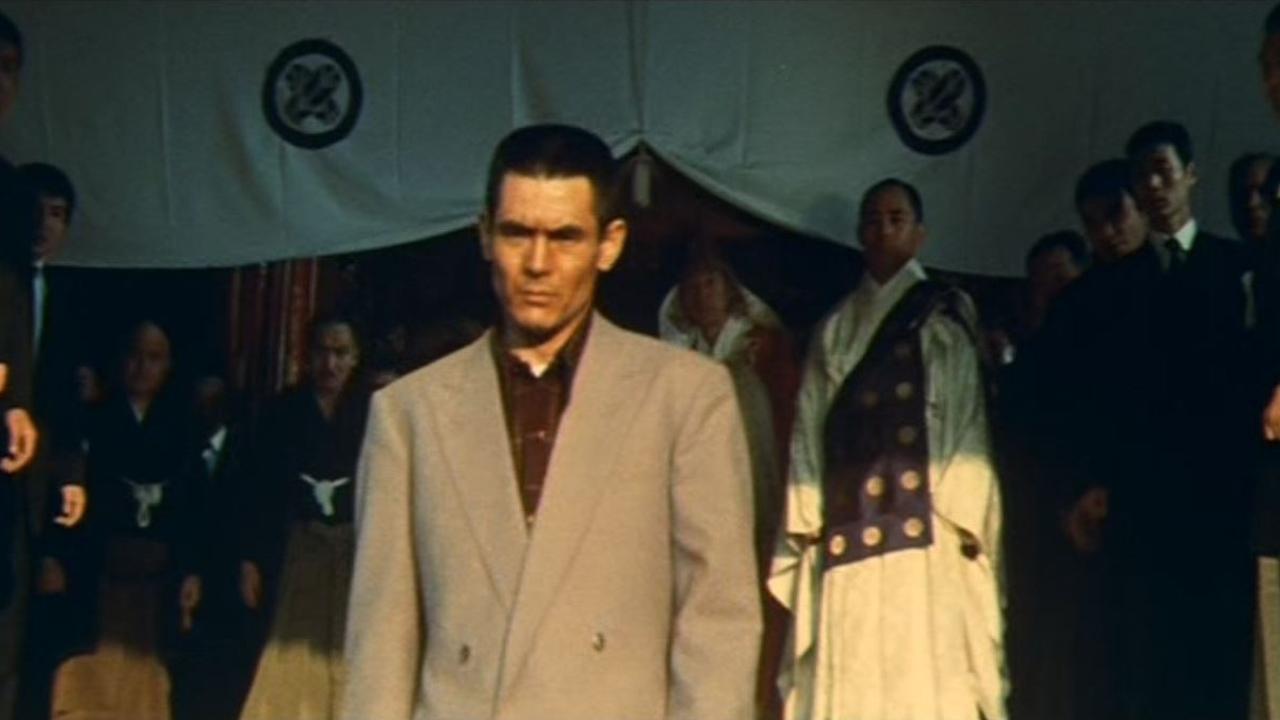

2. Faces (1968)

John Cassavetes first film “Shadows” in 1959 showed the world what a handheld and documentary approach to films could be and do. But after some Hollywood films, he returned in 1968 creating an unflinching look at marriage and modern relationships, resulting in a true birth of his style and themes.

In “Faces,” the film was shot on high-contrast black-and-white 16mm film stock, which shows a harshness and brutal approach to John Marley, Gena Rowlands, Lynn Carlin Seymour Cassel, and the rest of the cast. The film has been called, like many of Cassavetes’ works, a home movie of sorts. And that can’t be dismissed. The honesty and rawness of his characters are revealed in the camera approach.

The camera is always mobile by being in someone’s hands, such as when it pans crazily when Cassel literally runs onto the rooftop, or how the camera gets intimately close and slightly more still and erratic when Carlin’s Maria nearly dies. The camera is so intimate that it adapts to what is going on in the house in the film. It knows when to give the appropriate distance to the actors, or an extreme closeup for when inner truths are revealed.

It’s almost scary handheld camerawork because the characters and the story don’t hold back. Cassavetes lets the camera show all the flaws of these people, resulting in an honest portrait of people as his films always do.

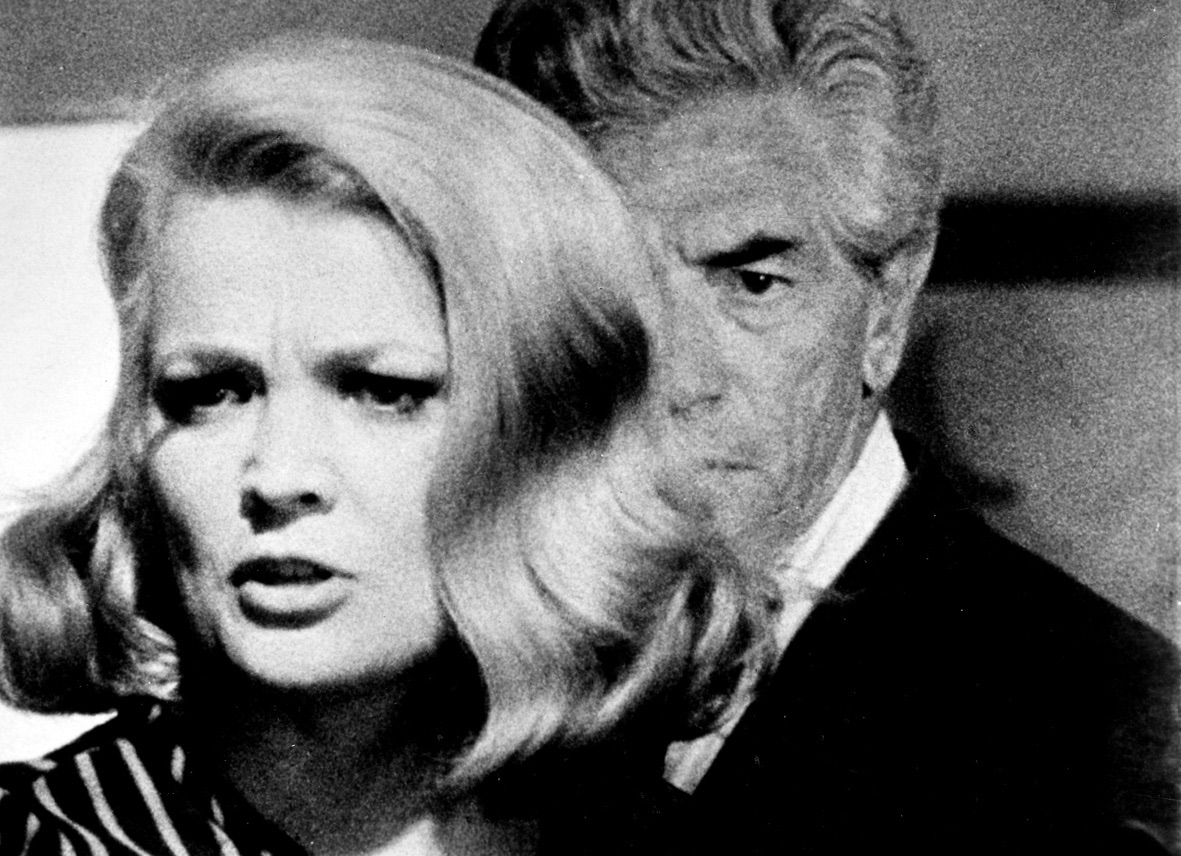

3. Husbands and Wives (1992)

Woody Allen has even cited Cassavetes for inspiration. But why, after nearly three decades of portraying New York characters in relationship highs and lows with controlled camerawork, did he want handheld for this film? “Husbands and Wives” might be one of the dirtiest and darker films Allen has made, and he was able to get this with handheld camerawork by frequent collaborator Carlo Di Palma.

Allen’s characters and story are full of smart, witty, clever, and of course, searching for happiness in New York, but there’s a certain edge due the style of choice. As the viewer, we feel a little more uncomfortable about what’s going to come of these characters and the choices they made. It’s bit darker in setting and tone. Sure, we get the comedy and truthfulness, but it’s a bit more painful this time around.

Maybe since it was toward the end of his relationship with Mia Farrow that he wanted something more dirty. Or maybe his own character can sum it up best when he is caught in one of the many arguments in this film with, “My sixth sense says you were unstable but on the surface you were, but now since we’re having all kinds of problems you, you’re not stable on the surface but not really this whole thing is becoming very clear to me.” Only Woody Allen could sum it up perfectly that way.

4. White Material (2009)

Claire Denis has always used handheld camerawork through the majority of her career, some films more than others. Even for specific segments capturing her truthful and lost characters in a dreamlike trance, struggling with their inner and external problems. But with teaming with Isabelle Huppert for “White Material,” she returns to Africa in pure handheld madness.

It’s not just the madness of the civil war about to erupt in the unnamed country, but the madness of protagonist Maria Vial, portrayed by the incomparable Huppert. The camerawork can almost be seen as a stream of consciousness of her mind and the country on a downward spiral.

The style of the film always behaved in a humane and relatable way, because she is trying to maintain her current lifestyle as everything, including possibly her inner psyche in getting lost. Denis’s camera captures the madness of Huppert and the world around her to include her family.

For example, the camera follows Denis regular Nicolas Duvauchelle racing to the young rebels on a motorbike, as he is clearly unstable in his choices. The camera tracks backwards, being placed on a truck, therefore resulting in keeping him centered and in focus but constantly moving in all directions. Denis knows what she wants and keeps her actors in a perfectly balanced mise-en-scene still with a handheld camerawork.

Denis is a master on how to capture actors in a time and space with handheld work, truly resulting in a high level of artistry and elegance.

5. The Battle of Algiers (1966)

As the film begins searching for terrorists and rebels in an underground compound, one can ask oneself, “Is this a documentary?” Gillo Pontecorvo used handheld camerawork in a mix of documentary and Italian neorealism to capture insurgent soldiers and citizens fighting for their homeland, with no actual real-life footage.

What makes the handheld approach unique here is the political and social context of this film. Could it have been this effective if shot in a traditional 1966 way? The answer is no. He did not want to glorify the struggle or side with the French or FLN, but rather wanted to be neutral, showing the realism of the war. Pontecorvo wanted to have a documentary and wartime newsreel style to the film and he succeeded, even in today’s standards.

The films holds up after nearly 50 years because we are witnessing history but with staged non-professional actors. He was mixing up the process of filmmaking and he made it authentic by having the camera constantly in a shaky, unnerving motion with real explosions and on location in Algiers.

No torture, shootout, or grieving family member scene plays out as staged or seems fake, as Pontecorvo was able to capture the authenticity of the struggle of the people by being perfectly placed with his mobile cameras. If shot in a staged or static camera world, the film would lose its tension and truthfulness, resulting in a far less moving and important film.