When making a film, the director has something to say, express or use the cinematic language as their canvas. Sometimes a film needs to be of epic proportions such as length or time to make that statement bold. On the contrary, some filmmakers are gifted in a way they can express and / or state what they want in 90 minutes or less.

There are dozens of great films that clock in under 90 minutes that leave an impression upon us, we can’t wait to see it again, we ponder at what we just saw, amazed at how much or little can be done in that time frame. On this list, you’ll see films that altered a country’s cinematic language or placement, changed up the filmography of a director, started a movement, and the list goes on.

A concentration will be placed on more obscure or under appreciated masterpieces. Also, a limitation to one film per filmmaker, one can easily take a number of Vittorio de Sica, Ingmar Bergman, or Robert Bresson’s film but to create a more diverse group of masterpieces under 90 minutes from world cinema.

1. Bicycle Thieves (1948) – 89 minutes

A film of epic proportions on such a minimalist and intimate scale, one can only wonder how Vittorio de Sica captured a relationship, post war Italy, social realism, and nothing but pure heartbreaking truthful emotion in 89 minutes.

We know the story as so much as been said about this film put after ‘Shoeshine’ (93 minutes), de Sica and frequent co-writer Cesare Zavattini inspired to something greater to capture the Italian people for who and what they really were. Despite initial warming up period of films in Italy Post World War II, it was The Bicycle Thieves that stabled Italian Neo-realism as a cinematic movement around the world that inspires us to today.

However, how did they achieve this, it all seems so simply executed as the camera follows the father, Antonio, and his son, Bruno, to find the bicycle. But out of this one action, we see the attempt of rebuilding Italy; the cruelness, caring, desperation, and optimistic society; the everyday life of the people; and a stunning portrait of a father and son.

It leads to a conclusion that will bring tears to one’s eyes after spending time with these characters, at the time non actors. De Sica states everything he was trying to explore in his films in 89 minutes and out of that, creates a cinematic timeless masterpiece and cements Italian Neo-realism as a major movement.

2. The Merchant of Four Seasons (1971) – 88 minutes

After cranking out 10 films in 3 years, Rainer Werner Fassbinder took a long needed break from creating films. His early films explored West German society and classes but it wasn’t until he discovered the American Hollywood Melodrama, particularly the works of fellow German director, Douglas Sirk, that he was able to express his views in fullest detail.

The story of the film follows Hans Epp played by minor Fassbinder regular Hans Hirschmuller, as he tries to find his purpose in society, his family, and overall life as a fruit vendor which leads to the self-destruction of himself amongst those around him which is really the tip of the iceberg.

In this film, similar to de Sica, Fassbinder gets a simple notion and explores countless relevant themes in the film such as mental self destruction, infidelity, class system racism amongst a heavy family melodrama in West German society.

This was not only a turning point of what Fassbinder would focus on for his short yet brilliant career, but we see his style change. The camera is precise whether static peering at the isolated, glaring characters; floating along the family’s faces for each particular reaction; painterly mise en scene; and the stark atmosphere he created amongst the family and people in a small apartment space.

However, it’s not just how Fassbinder hit new heights with this film technically and emotionally, this was the beginning of reshaping German cinema and putting it on the international map as he would continue to do so for the next 11 years in the most productive period of any filmmaker in history.

3. Rashomon (1950) – 88 minutes

After 10 films exploring samurai explorations, post World War II Tokyo, and noir films, Akira Kurosawa hit his breakthrough film with ‘Rashomon’ catapulting himself and Japan on the world stage of cinema. But it’s with this film, he changed the cinematic narrative in ways of storytelling, the subtext of dialogue and action for a scene, birth of one great actors, and numerous themes in only 88 minutes.

An example of a film where so much has been written about but for 1950, for Kurosawa to tell the same story through four different characters’ point of view was revolutionary. Now, we almost take it for granted but Kurosawa did it through the cinematic lens not as a literary device in which it wouldn’t seem so perplexing.

However, it’s not just the narrative of the four different tellings of the same story, it’s the discovery of the characters’ actions and reactions, the mood of his recurring nature motif of rain and sun shots, the lioness behavior of Mifune, the observing and careful Shimura, the ‘no frame is wasted’ approach to this film that makes this film timeless even today.

Kurosawa manages to ask the audience questions of man’s being and purpose, the morality of crimes, and who is right in what given situation. It creates an unsettling film experience as we continually question ourselves which story is the factual one, but it’s how Kurosawa used the cinema of ‘how’ and ‘why’ to create this masterpiece in 88 minutes.

4. Winter Light (1963) – 81 minutes

So far the shortest film on this list but certainly doesn’t mean the least effective. In the middle of his unconnected yet unified trilogy composing of ‘Through a Glass Darkly’ and ‘The Silence’, Bergman manages to explore themes of the existence of God, finding purpose in life by a pastor and nuclear era Cold War.

The film begins with Pastor Tomas Ericsson, played to perfection by regular Gunnar Bjornstrand, finishing his noon service in his church. The film follows Tomas’ life over the course of an afternoon, almost played to real time, as he deals with his inner questions on the silence of God, the parishioners questioning of their relationship, and a near fearful breakdown by Max von Sydow’s Jonas of nuclear bombing.

The plot glides along smoothly with the facial expressions of doubt and existentialist pondering of Tomas as he tries to figure out if he should continue to be pastor in this village. Despite Tomas questioning whether God exists or whether love is the most important thing in the world, he must advise his parishioners while he can’t even help himself. And these themes and questions are done through the cold, crisp black and white mis en scene frames that Bergman used, of course, captured by the incomparable Sven Nykvist.

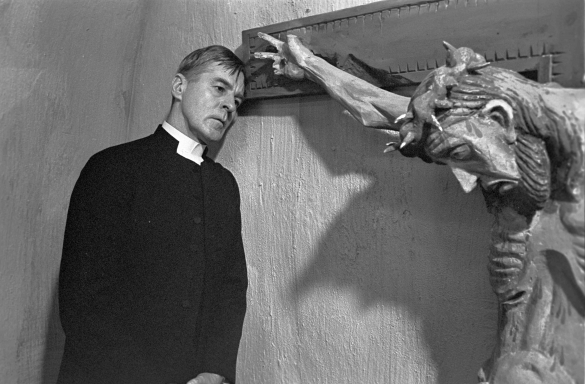

It’s particular frames that express what Bergman was stating in his film such as the high angle shot of Tomas on an isolated road, Tomas agonizing against a life size Crucifix, and of course, the beeming winter’s light through the Church’s glass window in which Tomas must continue to serve.

5. Mouchette (1967) – 81 minutes

Similar to the way Bergman expressed his world and thoughts, Robert Bresson did the same through his 1967 masterpiece ‘Mouchette’. Many people consider this film a continuation or exploration of similar themes he explored in his previous ‘Au Hasard Balthazar’ (95 minutes). So that’s maybe way he was able to express the cruelties and misery of a young girl which leads to tragic consequences in just 81 minutes.

The film plays out in typical Bressonian fashion, the use of absent frames, the concentration of hands over facial expression in montage style, the sparse use of dialogue, natural sound and design over score and soundtrack, but he does it so effectively, you feel every emotion Mouchette, played by Nadine Nortier, goes through and it’s heart breaking.

We witness, whether you want to view the film from a Brechtian distance or immerse yourself in the shoes of Mouchette, we most importantly feel the abuse of her teacher, the condemnation of her rapist, the slow decay of her mother, her alcoholic father, and even the bumper cars when she briefly smiles in the film. As the film progresses, Bresson manages to explore almost every single harsh reality of the human condition in his distinct style like no one else can.

As the film nears its conclusion in which seems, sadly and soul shatteringly to a viewer, that Mouchette must end things on her terms instead of the infliction of forces of nature and society upon her.

Even here, Bresson manages to extend the pain of her little short existence, that after a failed attempt at roiling into the lake, she repeats the action, but it’s only the sound of the splash in the lake we hear, we can’t even bear witness to her end, it’s left to us to visualize how Mouchette ends her life the 81st minute of the film.