In continuing the gold mining for obscure films around the world, and learning about different cultures through their rich artistic expressions, I’ve selected these 10 titles that deserve greater recognition.

1. An Innocent Witch (1965)

Japanese director Heinosuke Gosho has never crossed the border as his celebrated colleagues Kurosawa, Ozu, Mizoguchi and Miyazaki, among others, though his career is as consistent as that of all those cited, with a particular dedication to seek the beauty behind the sadness of common characters, an element that guarantees his best films an aura of fascinating melancholy. And it is worth noting, in this beautiful work produced by Shochiku studio, its language has survived impeccably to the arduous test of time.

The plot begins on Mount Osore, the entrance to hell, with the trepidant steps of an old woman seeking a blind shaman to help her get in touch with her deceased daughter. In flashback, we meet Ayako (Jitsuko Yoshimura), a naive girl from the interior who ends up having to work selling her body in the late 1930s, on the eve of the war, sacrificing her own life to feed her parents.

Upon arriving at the brothel, it attracts the attention of a repulsive older man who pays for the exclusivity of her services. The camera in the claustrophobic photograph of Shinomura Sôzaburô reinforces the confinement of prostitutes, often filming them through vertical wooden beams that simulate the bars of a prison.

Without revealing much about the development of Hideo Horie’s script, she will indirectly become involved in three client deaths linked by a family bond, something that will awaken in the hypocritical, sexist and ignorant society at the time; the fame that it is possessed by demons.

The intense third act displays a brave criticism of organized religion, highlighting the psychological damage that dogmas and ritualistic lies have caused the protagonist, who, believing herself to be guilty of all that has happened, agrees to go through the ruthless and stupid ceremony of supernatural purge.

Ayako, a pure flower of gentleness who was unable to respect the rigid code of never surrendering her heart to work, suffers humiliated before a bunch of arrogant, deluded and superstitious priestly vipers.

2. The Troops of Saint-Tropez (1964)

“An agent of order is always unpopular.” The phrase said austerely by police officer Cruchot, played by Louis de Funès in the first film of the franchise, synthesizes his hilarious devotion to work. When the dream of his troubled colleagues is shown in a moment of leisure, he is the only one who does not seek the pleasures of the flesh, only the heroic fulfillment of his function in society.

The French actor who charmed the audience with their faces and mouths is best known for “The Mad Adventures of Rabbi Jacob,” but I think his most relevant contribution is in the six projects of the Gendarme (police), especially in the first and third, addressed in this text, enriched by the killer chemistry of the protagonist with his superior in command, Gerber, played by the impeccable Michel Galabru.

“The Troops…” is uneven but has unforgettable sequences, such as the frenetic transition from black and white to color at the beginning, a troubled nun-driven car ride, and the police odyssey to arrest a group of nudists at the beach.

After several disastrous onslaughts, injured by a watchman sitting on the branch of a tree, the officers receive an embarrassing lecture by Cruchot, who outlines the most stupid strategy, something that might well have come out of the mind of Inspector Clouseau: training the men without uniforms, so that they come near naked from the place.

Without raising suspicions, they fight against time while they dress in their costumes, approach the nudist mourners, and in an ingenious touch of the script, ask for their documents.

3. Many Wars Ago (1970)

Francesco Rosi is almost never mentioned in lists, but his set of works is spectacular, having influenced names like Oliver Stone, Costa-Gavras and Gillo Pontecorvo, in addition to being quoted with much admiration by Francis Ford Coppola and Martin Scorsese.

Choosing to adapt the book “Un anno sull’altipiano” by Emilio Lussu, the director joins the author’s blunt speech, denouncing the insanity of war with a personal analysis of power relations in male groups, courageously confronting political clarity and questioning the interventionism.

Everything beautifully framed by the photography of Pasqualino De Santis (who would make Visconti’s “Death in Venice” the following year), creating unforgettable moments like the soldiers’ march through the smoke of the bombs, and especially the bluish night illuminated by the explosions in the war of trenches.

The plot approaches the despair of demoralized soldiers, led by a general (played by Alain Cuny) who’s willing to sacrifice his men even in unnecessary situations, by simple egocentric whim. Riot is a only a matter of time, when the nails that keep the monstrous and stupid machinery of war running end up realizing that death is a more dignified condition than the subhuman reality of existence.

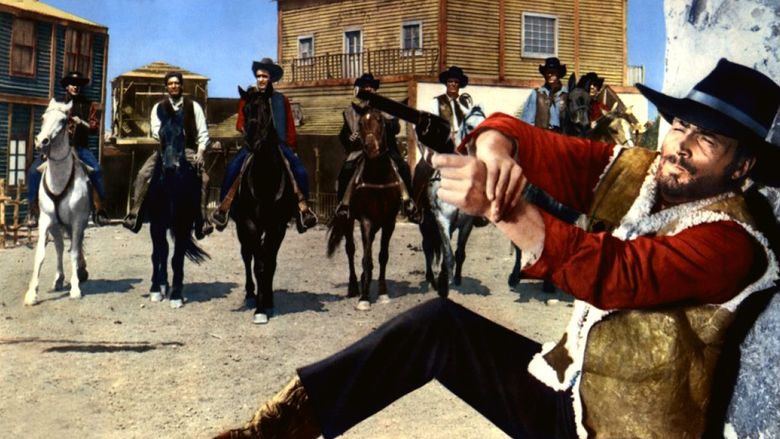

4. The Brute and the Beast (1966)

Italian director Lucio Fulci is recognized worldwide for his work in horror (works such as “Zombie 2” and “Dark Horror”), but he made some westerns, with “The Brute and the Beast” being his first and best work in the genre.

Franco Nero (coming from the recent success in “Django”) is associated with Uruguayan George Hilton (who would establish itself in the genre, including interpreting the mythical “Sartana”) in one of the best sequences of action already captured in the Spaghetti Western genre, which is only one of the qualities of this work.

The excellent soundtrack (by Coriolano Gori, with the theme song sung in English, as usual by Sergio Endrigo) and the violent whipping scene suffered by the hero were not only spared by the cruel action of the time, but managed to keep their efficiency intact. The comic relief in the figure of the smart digger (played by Chinese actor Tchang Yu) will induce the viewer to laugh with the same skill.

Inspired by the psychological western of Raoul Walsh, “Pursued,” the film was a watershed for the director (who would attract the attention of producers) and his two protagonists. Nero would confirm with this success with his lucrative charisma (replacing Giuliano Gemma in the eyes of the fans), while Hilton would build a career thanks to this supporting role, which eclipses the protagonist.

The high point (including inspiration for filmmaker John Woo) is the final shootout, where the show of destruction (prior to “The Wild Bunch,” which Sam Peckinpah would make in 1969) disrespects any verisimilitude, with Nero leaping acrobatically and already falling while shooting.

The images I keep in mind after the session are those in which the duo clearly amuses themselves while performing their revenge, exchanging arms with each other. The camaraderie between people who respect each other (even with differences), uniting in a common goal.

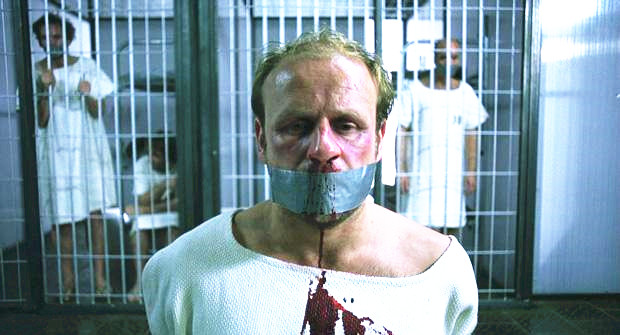

5. The Experiment (2001)

Director Oliver Hirschbiegel adapts Mario Giordano’s novel and turns it into a distressing cinematic experience. Knowing that this is a real story helps to keep our eyes from blinking as we get sucked into the plot.

A team of scientists summons 20 men from different backgrounds to a psychological experience in exchange for a cash prize. The participants are placed in a prison and randomly divided into two groups: eight of them play the role of guards and the other 12 of inmates. Prisoners must obey the rules imposed by colleagues who represent authority figures.

At first, comradeship reigns in the environment. But in a short time, the false guards change their behavior and violence (even if forbidden) fills in the gaps. The inmates become increasingly submissive and the guards increasingly aggressive.

A psychological study of unprecedented human behavior and a work that will hardly get out of your mind. At the end of the session, it is very clear that we only really know one person after giving them power.