Film is a extremely varied medium; there are films that entertain us with such effectiveness that we forget about the real world and we are left without a single moment to think.

Other films have other intentions and are crafted in such a way that we constantly think about the consequences of what we are seeing. The interest of these films is in making the viewer question life.

Here is a list of 10 films that do this with various techniques and styles, and manage fill our heads with questions on our own lives.

1. Stalker

Released in 1979, this film was the last that Andrei Tarkovsky shot in his country (the following two films were shot in Italy and Sweden). Acclaimed by some critics and fans as his greatest film, it displays the journey of three men through a post-apocalyptic land with the purpose to get to the Zone, where they intend to find a room that allows the one who visits fulfill their soul’s deepest wish.

None of the men have names; they are just referred as the Stalker, the Writer, and the Professor. Played by Aleksandr Kaidanovsky, the Stalker is the one who knows the way through the Zone and is in charge of leading the other two men to the room.

Through the journey of the three men, we see them have conversations that question the nature of the Zone and of life itself. In coherence with the characteristic style of Tarkovsky, the film is full of long takes, poems, and philosophical references delivered by the existentially anguished characters.

As the men get closer to the room, they begin to question whether what they think they wish is their truest deepest wish and at the same time, the oneiric mise-en-scene of Tarkovsky makes us question the nature of their voyage.

2. Blow Up

Based on the short-tale “Las Babas del Diablo” by Argentinian writer Julio Cortazar, this film, directed by Michelangelo Antonioni and released in 1966, is one of the most complex and thought-provoking films ever made.

The film was written by Antonioni himself in collaboration with legendary screenwriter Tonino Guerra. This adaption’s meaning is said to be far from the meaning of Cortazar’s tale. It won the Palme d’Or in the 1966 Cannes Film Festival.

The film displays the story of a photographer who thinks he may have been the witness to a murder and tries to unfold the mystery through the blow-up of a photograph he took in a park. But it is not precisely the anecdote that make the film so interesting.

One of the most common interpretations of the film has to do with the nature of truth and perception. In some parts of the film, Antonioni puts the audience in the distanced perspective of the main characters and thus neglects the necessity to understand its emotions and motivations.

This means that the audience is in the same position in relation to the main character and the film, as the main character is in relation to the murder, with only a few fragments of a reality that imply a mystery that is not possible to conclude.

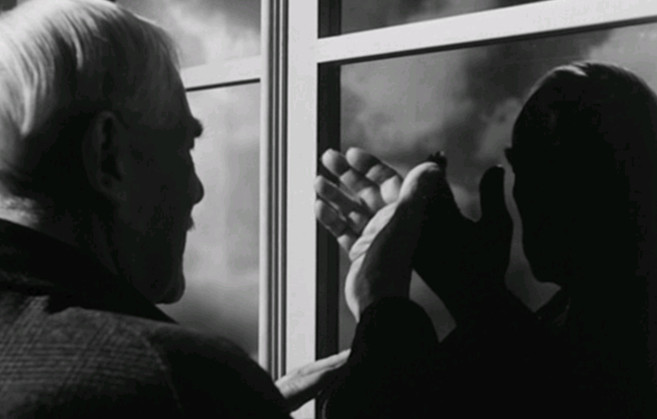

3. Wild Strawberries

Released in 1957 and written and directed by the legendary Ingmar Bergman, this film stars (for the last time) the great Swedish actor Victor Sjöström in collaboration with frequent Bergman collaborators such as Bibi Andersson, Ingrid Thulin, Gunnar Björnstrand and Max von Sydow.

The film is about the journey of a retired doctor named Isak Borg from Stockholm to Lund University, and during this journey, the old doctor meditates on his life and the past. The transformation of Isak and the perspective he has on life through the end of the film makes it one of most optimistic films of Bergman.

In his journey to Lund University to receive recognition for his career, Isak is accompanied by young people who, through the contrast of their personalities, make him question his behavior and perspective.

The interactions with the other characters, the journey, and his memories make Isak start reconsidering various aspects of his life as he discusses with the characters the way they feel about time, life and themselves. The end of the film shows a transformed doctor whose life he saw with bitterness at the beginning of the film, with new eyes that appreciate it much more.

4. Post Tenebras Lux

Written and directed by Mexican director Carlos Reygadas, this film won the award for Best Direction in the 2012 Cannes Film Festival. With a very personal approach and an unconventional narrative, the film displays various episodes in the life of Juan and his family. The relations between these episodes is ambiguous and leave most of the interpretation of the film in hands of the viewer.

Reygadas has been questioned many times on the meaning of the film, but he has constantly refused to give clear answers and has insisted on the importance of leaving the film with a degree of ambiguity in order to let the viewer participate in it.

The implication of the approach that Reygadas has with cinema is that the viewer is responsible for a great deal for the interpretation of the film, and thus he or she has a more active role in the film.

The film displays episodes of sexual violence, death, life, and childhood innocence, among many other themes. There is constant dynamic between the dark and the light of life: some of the aspects that Reygadas has cleared from the film is the meaning of the title, which means “the light after the darkness.”

5. Das Weisse Band

Internationally awarded in several countries, this masterpiece of Austrian filmmaker Michael Haneke won the Palme d’Or in the 2009 Cannes Film Festival. The film was also recognized in the United Kingdom and the United States, and it became one of the most complex and powerful films by Haneke.

The film is crafted with the mastery and precision of Haneke to create a portrait of a rural German town at the beginning of the 20th century. Techniques such as the distancing of Bertolt Brecht are used to first create a hermetic portrait, which is interrupted when the context outside of the town is clarified: the World War is just starting.

Haneke uses the town to talk about the nature of the world at the beginning of the century. The film explores how humans deal with morality and violence as a society: the way in which crimes are ignored and treated and how the nature of a group allows violence to happen is theme in this film. Haneke uses complex formal techniques to create this portrait, in which we as viewers are put into a privileged position in relation to the characters.