Our mottled, bustling, and multicultural planet is doubtlessly a charming reflection of Pandora’s box. Since the very first rational ideas until the most complex organizational rulings, and from an Amazonian tribe’s unrecorded principles to China’s precise totality of precepts, you can fathom the intentions for a collective freedom that is both pursued and shrank by norms and prohibitions.

On that long and ragtag way, a culture’s steps could sheer in one of the countless existing paths, or just find themselves unfitting in the footprints of other cultures. Along these lines, Nobel laureate Bob Dylan was unwelcome in Beijing and Shanghai in 2010, due to the rebellious socio-political content of his music, while Gustave Flaubert’s acclaimed classic masterpiece “Madame Bovary” elicited awe and aversion in France, back in the 19th century.

Combining psychology, politics, and aestheticism into one solid unit of ideas, cinema becomes the most describing and challenging form of art. A film’s character could comprise a graceful achievement for a place of the world and a shame for another.

On the other hand, a lot of qualitative motion pictures used to caress untouchable thoughts of a past that are now liberated. Typically related to political changes, religion, and sexuality, even works of great influence like “The Birth of a Nation” and Stanley Kubrick’s “A Clockwork Orange,” didn’t receive the equivalent recognition right away.

Diversity is one of the planet’s greatest features, on every level. Thankfully, our societies more and more realize that in order to maintain this diversity, we all need to accept and appreciate the cultural characteristics of other countries and civilizations, instead of rejecting them. Thus, the following films have been observed from a more sympathetic point of view through the years, in their own countries or globally.

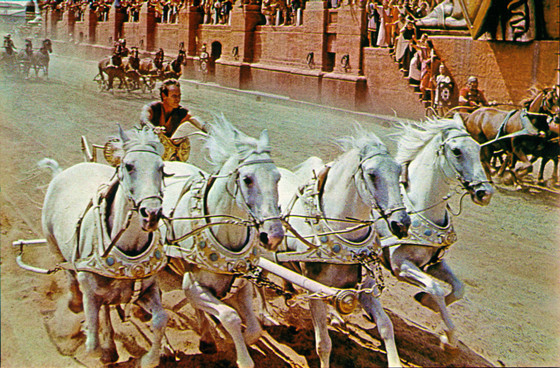

10. Ben-Hur (1959)

Winning 11 Academy Awards in 1960, the spectacular biblical tale “Ben-Hur” comprised a total triumph upon its release in the United States. Τhe picture’s extremely expensive production and almighty demanding technical requirements resulted in an impressive outcome, in relation to its visual elements and exposition. Despite these facts, Mao Zedong banned the film’s projection in Chinese theatres due to the story’s clear positive placement toward Christianity.

Of course, “Ben-Hur” is inspired by The Holy Bible, telling the story of Judah, a fictional lord of Judea who never lost his faith during his unequal battle against the overbearing Roman Empire. After a long journey that brought him close to Jesus several times, Judah recovers his prestige and claims a better future for his people.

During this course, a constant contrast between evil and virtue and an overpowering clash between grace and defect point to the most primitive values of kindness, hope, effort, and forgiveness. In a simplistic contextual motif, American director William Wyler found a rough landscape upon which build one of the most astonishing epic films ever made.

From one point of view, this is a story about blind faith and miracles. From another, brighter point of view, though, this is an allegorical legend that reveals some truths about the people and the culture of our mundane past. Nowadays, irrespective of the varied religious beliefs and ethnic characteristics around the world, this film’s majesty is globally well known.

9. The Outlaw (1943)

Not a lot of films have been banned in the United States. Representing a place of discoveries, renaissance, and cultural fusion, the “Land of Milk and Honey” has been allowing liberty of expression for a long time now. The 1943 noir-ish romance “The Outlaw” used to be highly infamous in the U.S. back during the 1940s. Jane Russell’s physical exposure, the reason behind the film’s former bad fame, is now abolished, and thus, a new sighting on this cinematic work has taken place.

Still, the film’s composition, narrative, and thematic directions aren’t what one would assume for an American film of the ‘40s. Sometimes slow, sometimes confusing, and sometimes even blurry in relation to its characters, “The Outlaw” could alienate, tire, and disappoint a prejudiced audience. However, its unconventional and artistic style attracts another audience that seeks indulgence in the individualistic and paradoxical aspects of this vintage American film.

Viewers and critics from around the world have reclaimed from obscurity this erstwhile infamous and contemporarily forgotten gem, appreciating the profound delineation and blending of its characters, pondering over the untraditional protagonist features, and experiencing the story’s somehow maze-like wandering through space and ideas. Essentially, this is a ‘40s film that seems like a ‘60s film. This is its gift and its curse.

8. Persepolis (2007)

Posters of Marjane Satrapi’s animated film “Persepolis” mention the words “war” and “revolution” among life’s parts of growing up. Arguably, not all of us have experienced wars and revolutions while coming of age. But this is a personal story that belongs to Satrapi and to all those who’d be delighted in understanding her life, exploring one of the world’s space-time settings, and winnowing out personal pieces as well.

The cinematic version of the comic book “Persepolis” was banned in Lebanon, since its content was considered a threat for the unstable political status of the Islamic countries. In 2008, one year after the film’s release, local artists and intellectuals stated their opposition, achieving the withdrawal of this prohibition. A few years later, in 2013, the original comic book was banned from classrooms and libraries in Chicago. This move was also overturned by social outrage.

In its engaging storytelling and pleasing animated imagery, “Persepolis” indeed exposes and criticizes the current cultural and political aspects of Iran, which are obviously set in contrast with the different cultural character of the Western world. Despite that fact, Satrapi’s autobiography, innocently given, is an honest, respectful, and questioning comment upon her societal environment and personalized placement in it.

Nowadays, 10 years after its synthesis, this charming, black-and-white dive within Iran’s painting progressively becomes more famous and acknowledged around the world.

7. Night of the Living Dead (1968)

The 1968 cult classic “Night of the Living Dead” was a commercial success during its first appearance in the cinemas. The sense of beholding the face of death provides a conscious victory, especially to the youths, and thus, George A. Romero’s first dreadful fruit was very appealing back in its days, perhaps for the wrong reasons.

Showcasing surreal situations of excessive violence and mastering an unprecedented kind of dystopian fantasy, “Night of the Living Dead” is considered one of the best works ever made in the territories of horror cinema. Apart from its technical adequacy and intelligent structure, however, the movie has a second contextual layer, satirizing the uncontrolled consuming nature of the living and tumbling the rising materialistic delirium of its era.

Currently, the film is worldwide acclaimed as a qualitative piece of the seventh art, since its visual extremity is integrated in a wider framework of social criticism and esthetic pictorial depiction. Nevertheless, more than 40 years after its release, Romero’s emblematic work is still banned in Germany. In an era that allows every spectacle and thought to be projected and articulated, such a prohibition is a strange fact that most people don’t know.

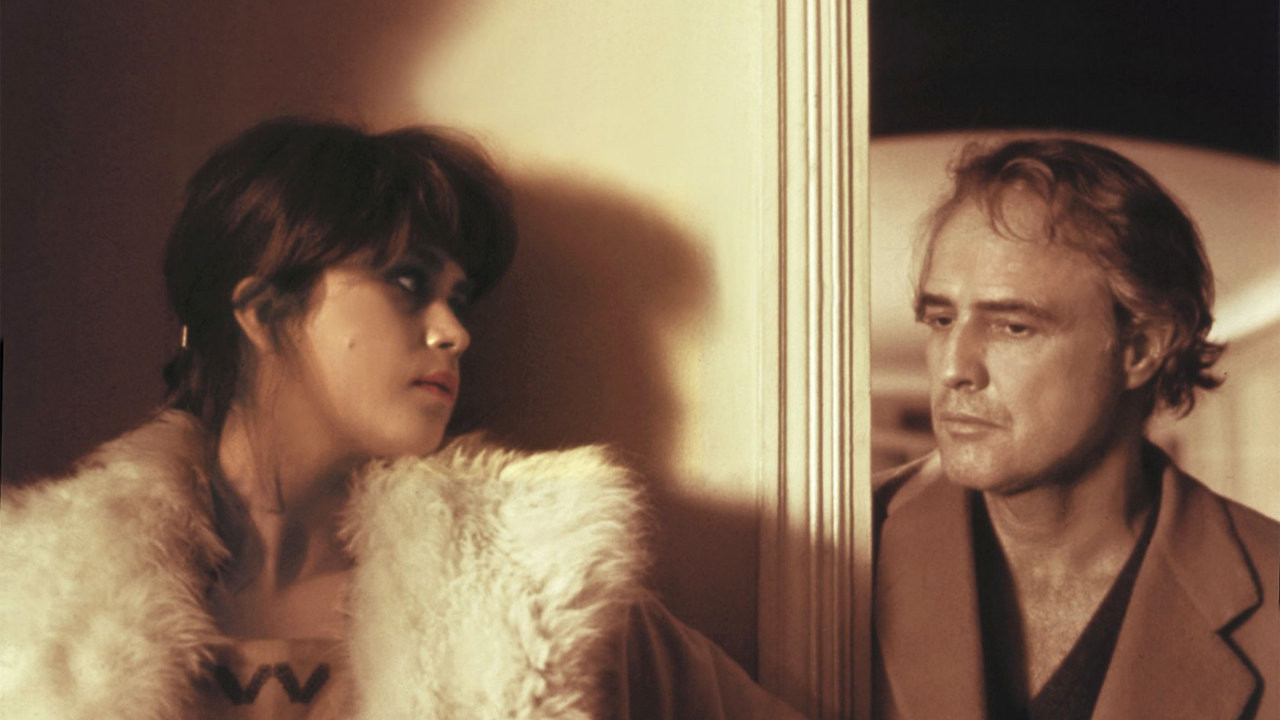

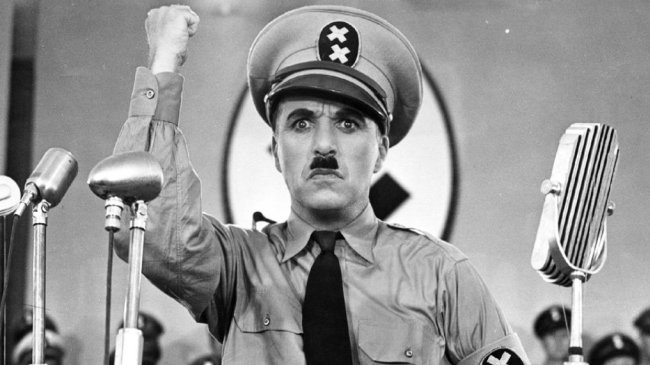

6. The Great Dictator (1940)

In 1940, our beloved Tramp acquired a voice. Still funny, direct, and honest, his voice came from the era’s deepest layer of oppression so as to deconstruct the world’s silently accepted delirium in two cinematic hours. Charlie Chaplin’s legendary “The Great Dictator” accepted severe criticism from several socio-political factors, since it fulfills art’s most essential scope: the consciousness awakening.

In a double role of a poor Jewish barber and a dictator, Chaplin suggests that it’s just one of our kind’s aspects behind every societal role. But the annoying part was that the barber could be anyone, whereas the dictator had a specific well-known name in the current reality stage. Juxtaposing the two dominant characters, the story’s satire soothes and reveals its core at the dictator’s unforgettable six-minute speech.

The film was banned at the time in Germany, Italy, Spain and Latin America, whereas backstreet motivated procedures were meant to prevent its release in the United States. Forthcoming political changes progressively allowed the projection of “The Great Dictator” in all the former Nazi-occupied and Nazi-friendly countries. In any case, no parameter could ever hamper the great influence of Chaplin’s first talking motion picture on cinema, art, and sociology.