David W. Griffith was the pioneering director who invented and introduced the original grammar of cinema as we know it today, but there are many who took the principles and developed them into an art form, and formed the grammar of cinema in different but influential ways.

1. Alfred Hitchcock

It’s no wonder Alfred Hitchcock is one of the most remembered and studied masters of cinema. The powerful language of his films could speak to both ordinary and élite audiences and it has well passed the test of time.

Having worked in silent cinema, Hitchcock developed his cinematic taste and understanding of moving image before sound was added to the film and this plays a key role in his cinema. He once famously said to Francois Truffaut: “The silent pictures were the purest form of cinema; the only thing they lacked was the sound of people talking and the noises … In many of the films now being made, there is very little cinema … When we tell a story in cinema, we should resort to dialogue only when it’s impossible to do otherwise.” This quote summarizes his approach to his filmmaking and his subjective use of camera.

This vision helped him develop his unique visual style and by the use of numerous techniques including his subjective use of camera. In his films, camera movements are designed to direct the audience’s attention and emotions as if the camera is telling them exactly where to look and what / who to follow. Such style together with these different forms of editing created a very powerful visual language that, most of the time, almost needed no dialogue or further explanation.

Almost every Hitchcock film is full of very carefully designed and masterfully performed shots, which are bricks in an elaborate structure. His camera works are among the finest of their kind in cinema history and have been repeatedly employed in other films: the use of dolly zoom in “Vertigo” (1957) to show the condition of vertigo and dizziness, or the remarkable opening shot of “Rear Window” (1954) where the location of the story, the protagonist, his condition, his job and his neighbors are all introduced in a travelling shot, which takes less than a few minutes without a single word.

However, Hitchcock films are also among the finest examples of editing. By the time Hitchcock started filmmaking, the essential rules of editing were hard-coded and well established by pioneers like David W. Griffith and Sergei Eisenstein, but Hitchcock managed to take editing to a new level in his films. His use of shot, reverse shot and POV shots were unique in terms of being able to tell the audience what the character is thinking in that scene or moment. He had the same approach toward showing shots of objects through the order of images, and he put emphasis on the objects in his films and somehow would create a dramatic meaning for them.

Another creative use of editing for Hitchcock was what he called “assembly”, which he mastered in the likes of “Psycho”; nearly 78 shots used in the editing of the super famous shower scene which only takes 45 seconds. Hitchcock said that it was a choice initially because of the censorship at the time, but this scene indicates the sheer power of editing and the illusion of a stabbing scene which the audience never see in a complete shot, one of which they are shown only fractions in the scene.

Where only having one such scene would be a win for a movie, Hitchcock shocks the audience and shows his intelligence with a different editing approach for second murder, where he jump cuts from a high angle medium shot to a close-up to create a jarring and shocking effect, which he called an orchestration, and yet is very different in the image sizes, shot orders and length of shots to the former one.

“Psycho” not only became an instant classic; it influenced generations of filmmakers to this date and among them, Martin Scorsese was inspired by the shower scene and basically designed his shots and edits in one of the fight scenes in his tragic boxing drama “Raging Bull” based on it. And yet Hitchcock films continue to inspire generations of filmmakers.

What makes Hitchcock a visionary, after all, are the ideas he had behind his grammar in film. Since he believed watching films is a very similar experience to the act of a voyeur, through his style of cinematography, editing and imagery, he constantly puts the audience in a voyeur’s place and invites them to see the world through the voyeur’s eyes. This creates a strong subtext, which makes his films and his ideology on cinema very remarkable and the only one of its kind.

2. Stanley Kubrick

Starting as a photographer for Look Magazine, Stanley Kubrick certainly managed to keep his photographic eye. From his very detailed compositions to the use of vanishing point and wide lens, Kubrick films are definitely among those that can be called photographic, and his stylish compositions and use of camera and lighting have influenced cinematic storytelling during his time and after him. If you wonder where you’ve seen the geometrically composed shots of Wes Anderson, you don’t need to look any further than Kubrick films.

Yet it was not only about being beautiful, but about telling the story in a stunning visual style and more importantly, creating the meaning in his cinematic world. Kubrick had a special interest in using wide lenses and he exploited it fully to create the moods and ideas his films needed, whether it was the distant sense of cold in Alex’s family in interior shots of “A Clockwork Orange” (1971) or to emphasize the isolation and loneliness of Jack and his family in the creepy and exaggeratedly spacious hotel in “The Shining” (1980).

Kubrick will be remembered for many of his qualities in filmmaking, but if only one example makes it to the film history books and film schools, it is no other than the genius match cut in “2001: A Space Odyssey” (1968). How can you show a concept as complex as evolution in a purely cinematic way?

The answer is by a match cut but a very smart one; yes, it is the iconic match cut of a bone floating in the air to a bone-like spaceship, which goes from man’s first tool to man’s most advanced tool millions of years later in just a second. This match cut might be one of the only of its kind which indicates the real power in storytelling through edits, and Kubrick’s profound understanding of film grammar to convey such a difficult concept within a second.

Though this is not the only great moment in the film, as it is a great experience in terms of nonlinear storytelling with three separate parts which create a whole. For a film, not having any line of dialogue for almost two-thirds of its length and no linear story or main protagonist to follow, which is what Kubrick does with his visual storytelling and enigmatic look of outer space, is somewhat unprecedented and groundbreaking.

While there’s symbolic imagery in the film, it’s Kubrick’s great use of images, editing and music that creates an almost unique grammar for this film, and he even manages to take us through a voyage in time by the use of shots creating a time travel effect which was never seen in cinema before.

Kubrick was also a master of storytelling with light; from his famous candlelit sets in “Barry Lyndon” (1975) to the harsh low-key shots of “The Killing” (1956) and the lit-up interiors of “Eyes Wide Shut” (1999); not only did he have a very practical approach toward light, he managed to tell his stories with different lighting design to match the mood or period of the narrative.

“Barry Lyndon” still holds the record for using the lowest f-stops in film due to its natural lighting, which was of course to create a naturalistic look of the time of the events which resulted in painting-like shots never captured before on film, and redefined realism in historic / period dramas.

Last but not least, Kubrick was very influential for his understanding of rhythm in his films, which is a subtler thing to notice; he often used a slower or faster pace in certain parts of his films which was not that usual in film before his time. “Barry Lyndon” is a typical example where there’s an intentional sense of slowness in most of the shots; Kubrick even put some very slow zoom-in or zoom-out shots in certain scenes to emphasize on the slow rhythm of life in 1800s, and hence to create its own grammar of the film.

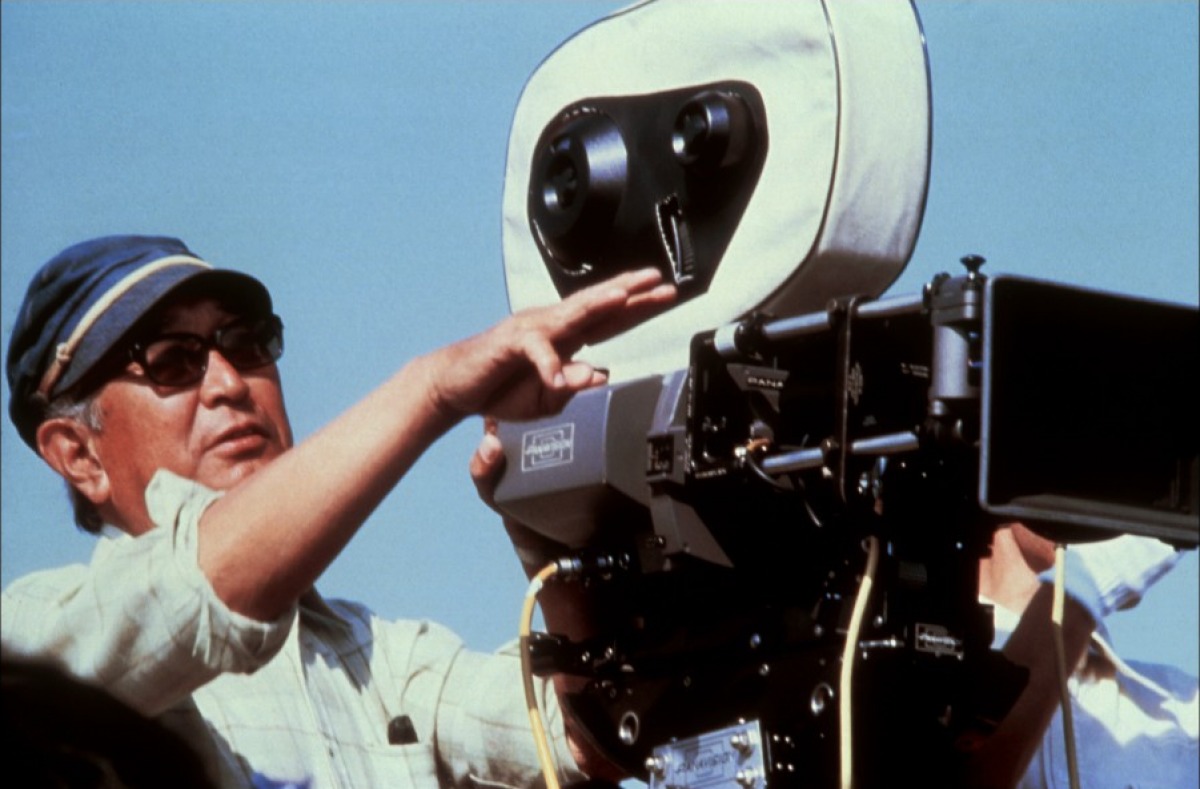

3. Akira Kurosawa

Akira Kurosawa is an interesting case in film history, which stands in the crossing of classic and modern cinema. He has made films with both narratives and is influential and memorable for different reasons and for many of his films.

However, maybe the best case for understanding his influence and importance in further developing the grammar of cinema should be with “Rashomon” (1950). It’s the first film that earned him international acclaim and attention and is a milestone in modern storytelling; the now-familiar narrative is about a murder story told from different perspectives, and not only does it vary in details each time, but the film refuses to offer a solid ending or resolution in any of the versions.

Here lies the genius of Kurosawa as a master visual storyteller; in a film about uncertainty, the composition of each image and order of images both lead the audience to uncertainty, while it was an established convention of the classic cinema to lead the spectator toward unity and clarity. Kurosawa uses its images with compositions full of diagonal lines which go around the frame, and he depicts the murder in a forest covered in shades to create that underlying blurriness in the story through his images.

Another unique reason to have Kurosawa on this list is his exceptional ability to use natural elements, such as wind or rain, and in general movement in his frames, not only as a powerful element in his images but also as a subtext to the actions happening in the scene or throughout the film. He has also used mountains and hills as another natural element in his mise en scène to portray his characters’ status or state of mind. The latter can be seen most significantly in his late 80’s masterpiece “Ran” (1985).

A painter in his early youth, Kurosawa did have an eye for color in his color films from the late 60s onward, and color was used as a major element in later epic samurai movies such as “Ran” or “Kagemusha” (1980) as mean of storytelling.

Kurosawa continued to be a visionary with his visual storytelling throughout his career and he went on to inspire a whole generation of filmmakers on other side of the world – the United States – where great names like George Lucas, Steven Spielberg and Francis Ford Coppola were admittedly influenced by him.

4. Jean-Luc Godard

A rebel in the true sense of the word, Jean-Luc Godard redefined what cinema and film language can mean or can look like. Having studied and theorized different ideas about film as a famous film critic in Cahier du Cinema alongside other musketeers (Truffaut, Chabrol, Rohmer, Rivette and others) who all became pioneers of the French New Wave, Godard had a very avant-garde and revolutionary approach to cinema.

With his now iconic debut, “Breathless” (1960), he started the French New Wave era and offered a new grammar to cinema. He employed various techniques including the innovative use of jump cuts (traditionally considered amateurish), breaking the eyeline match and direction of movement in continuity editing. This daring style divided audience and critics, but its influence on other filmmakers is undeniable, which later even led to creating video clips that basically used this new order of putting images together to create an idea.

But being a true experimentalist at heart, Godard continued to challenge the cinematic form with more radical experiences such as asynchronous use of sound and narration on the images, or actors talking directly to the camera / audience, which were all borrowed and influenced by renowned playwright Bertolt Brecht and his famous method of alienating the audience and emphasizing the fact that they are actually watching a film.

This is contradictory to what is more conventionally intended in a film, which is to create an illusion of reality through the succession of a series of images and hence nothing should get in the way of the audience. Of course, Godard experimented and implemented this new grammar to involve audiences in a more self-aware state with the film and make them more engaged in his films’ contents.

In recent years, Godard continued to try other formats and experiments in his films including videos in In “Praise of Love” (2001), “Documentary in Our Music” (2004), and even a 3D film, “Goodbye to Language” (2014).

Though always a lone pioneer, his influence can be found all over the world including with Bertolucci, and early works of Soderberg, Tarantino, Hal Hartley and many more.

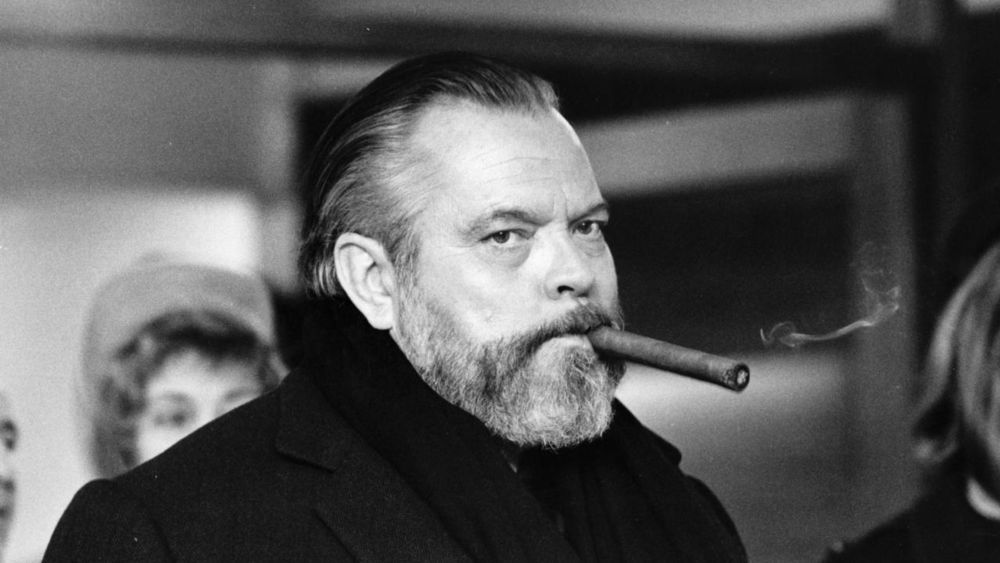

5. Orson Welles

Orson Welles’ “Citizen Kane” has long been crowned as the greatest film of all time by many film critics, directors and film buffs around the world. It’s no surprise, though. It was almost 50 years after the birth of cinema when “Citizen Kane” was released (1942) and yet the film showed an unprecedented uniqueness in its use of the cinematic language and techniques. However, it took several decades for the audience, film scholars and film institutes to really appreciate this truly remarkable masterpiece of filmmaking.

Only 24 at the time and heavily influenced by John Ford (another great master of cinema which is absent from this list), Welles used many different innovative techniques to tell his complicated story. In fact, though “Citizen Kane” is made in the period of classic Hollywood, its style of non-chronological events and combining different narratives defies the rules and grammars of classic storytelling at the time.

There were arguments by film historians whether or not Welles should be credited for the invention of many techniques used in the film, but there is one thing all agree on and that is that Welles has used them all in the best creative way possible and somehow took the medium of film to a new level. Welles used techniques such as deep focus cinematography, shots of the ceilings, high-contrast lighting and jump-cuts all in a very expressionistic way. Though these techniques existed before him, this film and some of his other works still are best examples of their purposeful use.

The innovative choice of wide lens and large depth of field is maybe among the most famous and remarkable techniques of the film; the scene in which Kane’s parents and his would-be guardian discuss arrangements inside the house, while the young Kane plays happily with a sled in the snow, is still the most creative use of wide lens and depth of field to tell a story in one frame but two layers with no cuts, and the film has several occasions where there is action in both the foreground and background and they are usually dramatically connected.

The film also has a couple of long takes and tracking shots that were also groundbreaking technical achievements at the time, which were not only a directorial act of technical showoff but an attempt at creating a new language for film. Just to make it harder for himself and his cinematographer Freddie Young, there is even a shot where camera goes through a glass ceiling to introduce us to the one of the characters.

But this profound vision toward the grammar of film can be seen in other works of Welles as there was no end to his cinematic ambitions. “A Touch of Evil”, a film noir he made 16 days later, opens with one of the most iconic long takes in film history: the shot starts with an insert, opens up to a medium shot, and as the camera follows a man, it suddenly tilts on a crane, goes all the way around a building, introduces the lead characters of the film as they are followed by the threat shown in the beginning, and after a breathtaking three and a half minutes, it cuts to another shot.

What Welles has done here is pure cinematic storytelling, and offers a lot of details in the first minutes of the film and also keeps the audience engaged in the scene by showing them a ticking bomb at the very start. There has been a good number of excellent long takes in cinema ever since and more advanced technology has made it easier over the years, but this opening shot probably remains among the finest examples of proper employment of such a technique in film.