As we view a cinematic work, elements like narrative and plot structuring are indispensible to our judgment of it, even if we don’t notice their relevance right away. The way a story is told, an idea is explored and an artistic sensibility is expressed determines, to a large extent, our personal preferences when it comes to films.

The sound and the image are inextricably linked to these elements and form our first contact with the film. But they must be complemented by a vision that controls their hold over our senses. That is where the screenplay comes in.

Fascinatingly, the filmmaking process works in reverse. The screenplay is the initiator, giving cinematic form to an idea that is born in the head of the screenwriter. The idea is translated into words, descriptions of atmospheres, moods, settings and other instructive mechanisms that then allow for a translation of this idea on the screen.

Of course, many alterations are inherent to this transition, especially in cases where the director is not the screenwriter. The actual production and post-production gives leeway to discover new stylistic approaches to the attaining the goals defined in the screenplay.

And yet, the foundation of a great film is more often than not, rooted in a screenplay. The path can be changed during filming and in editing but the journey begins with the script. Notable screenwriters have constantly redefined how films are structured and how the cinematic language can be put to better, more efficient use by constant experimentation.

So here are 20 of the greatest screenwriters of all time.

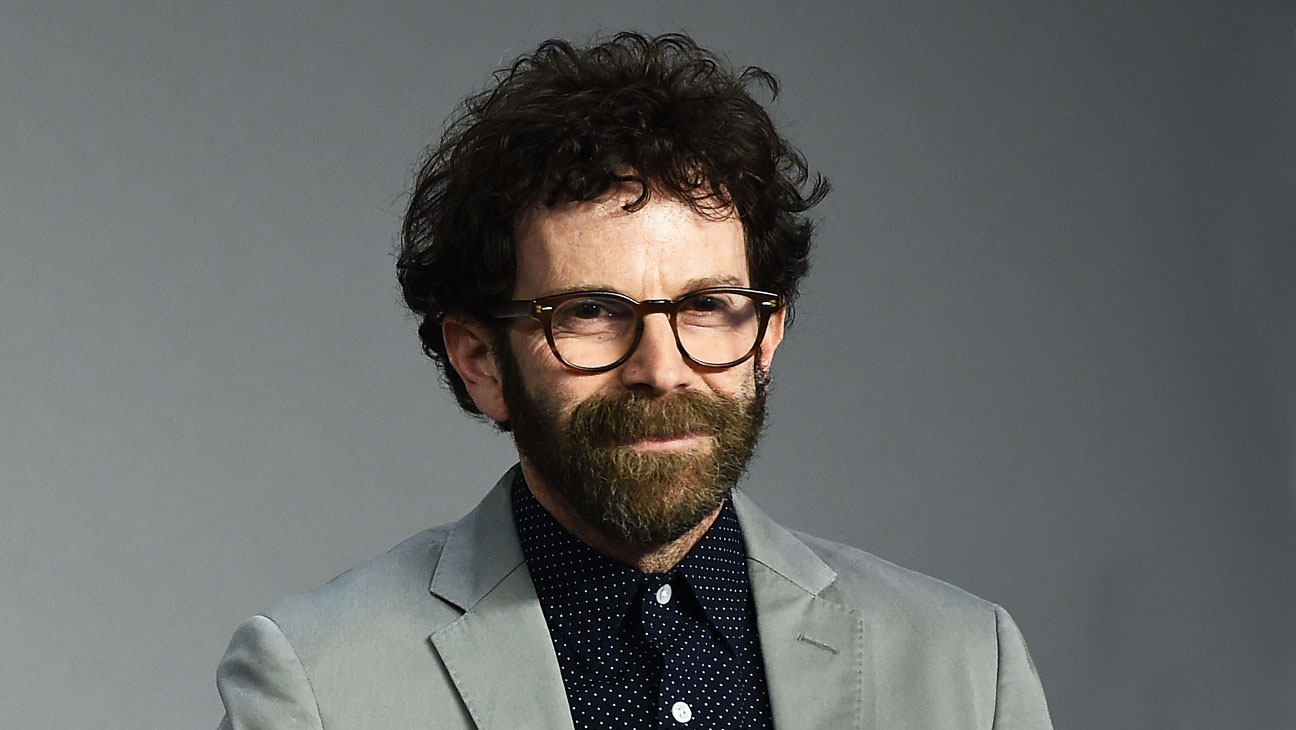

20. Hayao Miyazaki

The Castle of Cagliostro, Nausicaä of the Valley of the Wind, My Neighbor Totoro, Kiki’s Delivery Service, Porco Rosso, Princess Mononoke, Spirited Away, Howl’s Moving Castle, Ponyo, The Wind Rises

No one in film history has captured the sincerity of a child’s sense of wonder, fear, adventure, courage, righteousness and intelligence with the level of towering imagination as Miyazaki has. His command on the animated worlds he creates surpasses any other filmmaker who has dabbled in the medium. His characters are joyfully entrancing and his fantastical stories seem to know no emotional, intellectual or artistic bounds.

Known for his indelible attention to detail, Miyazaki composes his pieces like vividly luscious symphonies. The high notes are always unfamiliar and exciting and the low ones are gratifying and melancholic. His visually resplendent creations never fail to intoxicate both children and adults with their uncharacteristic honesty.

While a lot of his work like “My Neighbor Totoro”, “Princess Mononoke” and “The Wind Rises” has influenced generations of anime artists and animation filmmakers, his greatest accomplishment is “Spirited Away” that conclusively proves his metal and makes evident everything that makes him so endearing to his audiences: limitless ambition, incredible detailing, and a strong female protagonist who knows how to fight her battles on her own.

19. Ruth Prawer Jhabvala

Quartet, The Bostonians, A Room with a View, Mr. and Mrs. Bridge, Howards End, The Remains of the Day

The only person to have won both the Man Booker Prize (for her novel “Heat and Dust”) and the Oscar (for both “A Room with a View” and “Howards End”), Ruth Prawer Jhabvala is easily best known to film audiences as the writer of the Merchant Ivory films that formed their own sub-genre of period films with exquisitely structured, low-budgeted, yet ambitiously mounted masterpieces that radiated impeccable wit.

They owed a lot of their success to the Jhabvala, whose writing is so elegantly prosaic and transporting, but also delectably smart and at its very best, a refreshingly ironic take on the British upper class. The pace and the performances were zany and recognizably economic. But the films were also masterfully restrained and beneath the surface, contained sweeping emotion and depth.

Her most memorable work is undoubtedly the scathing Merchant Ivory classic “Howards End” which stars British legends Anthony Hopkins, Vanessa Redgrave and Emma Thompson and subtly peels every layer of hypocrisy that the society of the early 1900s harbored. With immeasurably delicate performances, it also remains one of the most socially relevant films of all time.

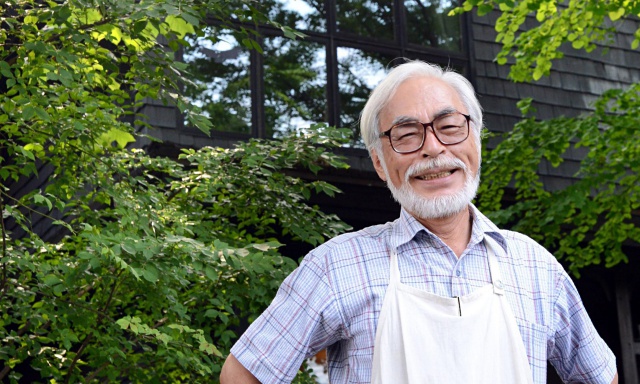

18. Béla Tarr

Almanac of Fall, Damnation, Satan’s Tango, Werckmeister Harmonies, The Man from London, The Turin Horse

Lauded as one of the most authoritative filmmakers of all time, Béla Tarr’s grand reflections of a deeply flawed humanity have made him a must-see for any serious film lover. His films move at a deliberately languid pace and are all filmed in breathtaking black and white (with the exception of Almanac of Fall), with long slow takes that patiently lend time to the audience for reflection and deeper understanding.

But benefiting this singularly monumental style of filmmaking is Tarr’s undeniable mastery at making his gorgeously absurd existential artistic endeavors silently, profoundly honest. His narratives never feel out of place or even out of proportion with the setting or period, but seem to contain within themselves generations’ worth of insight.

The two films that best exemplify this came one after the other in his filmography. In 1994, his magnum opus, the over-7-hour long “Satan’s Tango”, which was an impossibly bleak representation of humanity instantly made him a cinephile favorite. With 2000’s “Werckmeister Harmonies”, his control over the medium was incontestable and is easily one of the greatest, most imaginative works of art ever made.

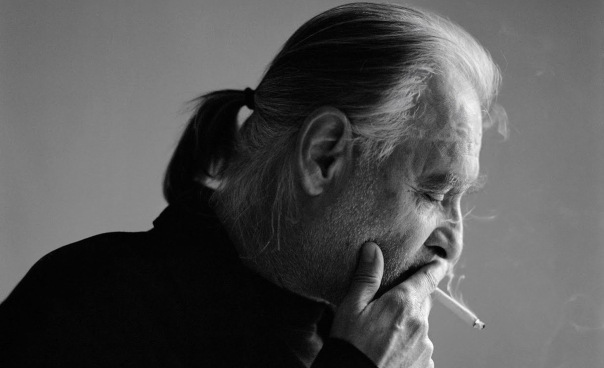

17. Robert Bresson

Diary of a Country Priest, A Man Escaped, Pickpocket, The Trial of Joan of Arc, Au Hasard Balthazar, Lancelot du Lac, L’argent

One instantly thinks of the minimalist, tender, incessantly moving “Au Hasard Balthazar” at the very mention of Robert Bresson, a filmmaker who according to Jean Luc-Godard was “French cinema”. Over his career spanning four decades, Bresson exploited the quietness and the muted imperfection of cinema to a vastly triumphant extent.

Filmmakers like Michael Haneke (who placed his “Lancelot du Lac” at second place in the Sight and Sound poll for the greatest films ever made) continue to cite his ingenious work as a huge influence. He worked largely with non-professional actors and like another master filmmaker Ermanno Olmi captured the essence of life through his contemplative use of mise en scene and astonishingly simple dialogue.

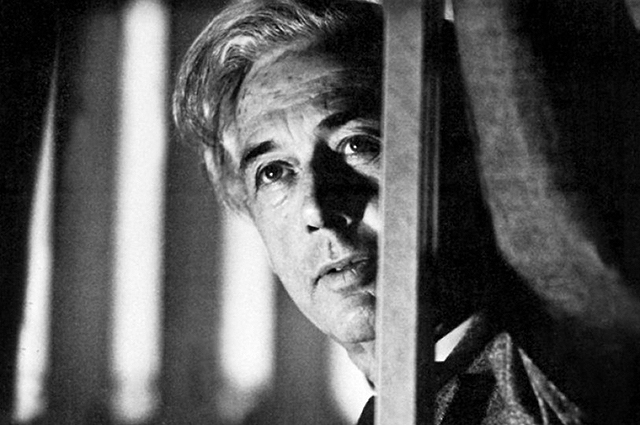

16. Akira Kurosawa

Drunken Angel, Rashomon, Ikiru, Seven Samurai, Throne of Blood, Yojimbo, High and Low, Kagemusha, Ran, Dreams

Handily the most well-known and probably the most universally beloved filmmaker from Japan, Akira Kurosawa was a game-changing global presence in context of cinema. He brought unprecedented attention towards Asian films and made way for other filmmakers from his country to be recognized worldwide. He was cited as the “Asian of the Century” in the “Arts, Literature and Culture” category by AsiaWeek magazine.

His films defied all conventions, ushering in a new style of entertainment with eye-popping visuals and riveting action sequences. But perhaps the most staggering achievement of his career was his skillful sculpting of characters. His narratives had all the elements to disturb, enthrall and amaze you, but his distinct, thunderously indelible characters enrich his works effortlessly, making him one of the greatest storytellers of all time.

15. Paul Thomas Anderson

Boogie Nights, Magnolia, Punch-Drunk Love, There Will Be Blood, The Master, Inherent Vice

There’s something to Paul Thomas Anderson’s writing and filmmaking style that has grown so steadily, in the most pristine terms over the course of his career and in his past few films has come to mirror a Kubrickian sense of ambiguity and atmosphere. His early films, although not as visually imaginative, capture a frenzied sovereignty and understated generosity of emotion like few other works of art in cinema.

Anderson’s characters like Lancaster Dodd and Freddie Quell from “The Master”, arguably his most accomplished feature, are so deftly apart from the world surrounding them, and yet work as perfect devices for Anderson to impart full-bodied, nuanced lessons on that very world. He can go from vicious, fierce irony to unclassifiable tenderness in seconds, best exemplified by the pace of “Magnolia”.

There is unmistakable variety in his work, but an Anderson film is utterly distinguishable because of his penchant for observant, contemplative dialogue and richly off-center characters can be found in every single film of his. “Punch-Drunk Love” and “There Will Be Blood” exist in worlds that never collide, except that they are flawless realizations of one brilliant screenwriter who immerses us into them like no one else could.