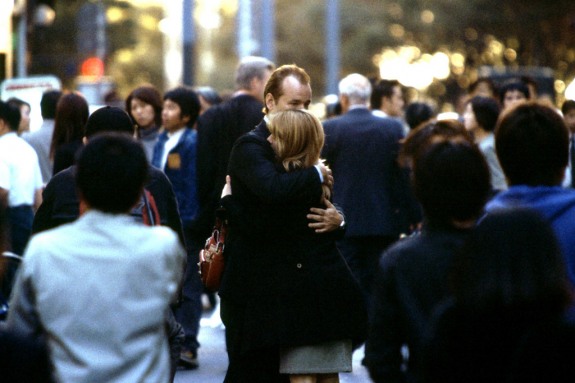

At a high school dance, four teenagers share a bottle of peach schnapps under a table. On her way to Versailles, a girl steams up a carriage window with her breath, trying to pass the time. After flying from Italy to Los Angeles, a father and daughter listen as a guitar player sings “(Let Me Be Your) Teddy Bear.” On a crowded street in Tokyo, a man and a woman hold each other close.

What do those moments have in common? That they each usher us into the souls of one or more characters and allow us to feel what they’re experiencing, be it giddiness, longing, or vulnerability. Also, they are all from movies written and directed by Sofia Coppola, who has made a career out of slipping into stories that are intimate, yet emotionally tower as high as the stunning Japanese skyscrapers in “Lost in Translation,” her Oscar-winning second feature.

Coppola’s countless gifts make it hard to rank her films from worst to best (when your credits include four imperfect gems and one of the most visually and emotionally transporting films of all time, “worst” becomes a relative term). Nevertheless, here are all her cinematic works listed in order of this critic’s preference.

5. Marie Antoinette (2006)

As the opening scene in which Marie (Kirsten Dunst) looks in the camera and flashes us a knowing smile suggests, “Marie Antoinette” is no straight-laced biopic. Yes, it’s about the life of the ultimately beheaded Queen of France, but it’s also flashy and unabashedly modern, thanks in no small part to a glitzy montage featuring fetishistic shots of shoes and a soundtrack that includes “I Want Candy.”

Given these subversive flourishes, it’s ironic that the film falls prey to a familiar biopic pitfall—it breezes through so many life-molding events (including births, deaths, a wedding, and a coronation) that they begin to blur together, thereby diminishing their importance.

Coppola should have realized that if you want to convey the impact of the life of a legend, you can’t let yourself get lost in the sweep of their existence (it’s better to delve into the intricacies of a defining moment, the way Ava DuVernay did to depict Martin Luther King Jr. in “Selma”).

And yet, despite that frustrating defect, “Marie Antoinette” is still remarkable. The scope of Marie’s journey through the movie may be vast, but within it Coppola explores thrillingly personal moments, like the ebullient scene where Marie and a troop of her friends frolic as they prepare to watch the sun rise.

That moment may not make you forget Marie’s notoriety, but by showing her and her comrades childishly goofing around, Coppola reveals that beneath all Marie’s gaudy finery is a young woman unprepared for the damning role in which history will cast her.

4. Somewhere (2010)

The growl of a black Ferarri’s engine haunts this somber and wrenching tale of a movie star drifting aimlessly through Los Angeles. That star is Johnny Marco (Stephen Dorff) and the deadening noise of his car is a metaphor for his staid existence. Johnny may make enough money to do whatever he wants, but actually doing he wants—including partying and staring at pole dancers—has turned him into a pleasure-guzzling zombie. For him, the world beyond his personal desires may as well not exist.

And then, one morning he awakens to find a luminous, smiling face filling his vision. It’s his 11-year-old daughter, Cleo (Elle Fanning), and her arrival marks the beginning of a journey.

Together, she and Johnny travel from the Chateau Marmont (the hotel Johnny calls home) to a cheesy awards show in Italy, and later to Las Vegas. Still, the geography of their excursions is less important than the internal trek that Johnny, an often-absent parent, embarks upon as he slowly awakens to the weight (and beauty) of his fatherly obligations.

This redemptive narrative is filled with reverberations of “Lost in Translation,” although “Somewhere” is a lot tougher to sit through. That’s because Coppola uses claustrophobic camera angles and punishingly lengthy takes (including the seemingly endless opening shot in which Johnny drives in circles) to make sure that you both witness and experience Johnny’s smothering ennui.

To put it more bluntly, passages of “Somewhere” are deliberately boring. But does deliberateness really excuse dullness? Not necessarily. However impressive Coppola’s attempts to place us inside Johnny’s stymied psyche are, they deliver an uncomfortable reminder that her weaker films are better-suited to be dissected in a lecture hall than screened in a theater.

So why is “Somewhere” so hard to resist? Mainly because through Johnny and Cleo’s interactions—especially during an entrancing scene where they gracefully float beneath the surface of a swimming pool—Coppola makes you feel every ounce of their love for each another. That’s what finally lifts the film far above Johnny’s static life, propelling him into the final shot when he walks down an empty, sunlit road, at last ready to live beyond the protective walls of his car.

3. The Bling Ring (2013)

“Let’s go shopping.” Those words, which are delivered with an intoxicated smile by Rebecca (Katie Chang), are uttered in the first scene of this suavely nasty, fact-based tale of teen burglars snatching millions of dollars’ worth of possessions from celebrity homes, including the dwellings of Paris Hilton, Orlando Bloom, and Lindsay Lohan.

Yet despite the law-breaking promised by that premise, it never feels like these crooks are in a crime movie, since they steal riches as casually as most people would buy a chocolate bar.

Anyone expecting Coppola to treat this so-called “Bling Ring” of characters with affection will be disappointed—the movie portrays most of them as soulless, spoiled losers. In fact, even when core Bling Ring member and wannabe celebrity Nicki (Emma Watson) is arrested and handcuffed, it’s difficult to muster any pity because her histrionic whining (“I want to talk to my mom!”) looks suspiciously like the opening act of a performance engineered to fill headlines.

At times, the simplistic characterizations of Nicki and friends make the film feel awfully hollow (especially when you imagine the punch that could have been packed by a “Bling Ring” populated by characters as sharply drawn as Bill Murray’s Bob Harris from “Lost in Translation”).

Yet “The Bling Ring” is still compelling because it refuses to excuse the kids’ actions by saying that they just loved Hilton and her ilk a little too much (Coppola seems to prefer the idea that the robberies were fueled by a materialistic hunger for more money, fancier clothes, and Lohan-level fame).

Eventually, that hunger leads to tragedy—by the end of the film, many of the characters have been sentenced to jail time. Yet the kids’ crimes make them famous in their own right, hinting that tabloid-celebrity culture is a noxious Möbius strip in which exploitation begets gratification, a thought which is neatly summed up when a particularly insightful interviewer tells one of the Bling Ringers, “And now you’re a star.”

2. The Virgin Suicides (2000)

The virgins may be in the title, but the most memorable character in this dreamy suburban saga is Trip Fontaine (Josh Hartnett), a high school football player described as having “emerged from baby fat to the delight of girls and mothers alike.” He knows it, too—shortly after he enters the movie, we see him swaggering through a hallway to the beat of Heart’s “Magic Man,” looking smug at his good fortune to be a teenager with a full head of hair, a scarlet Pontiac, and plenty of marijuana.

So why does a strapping dude dominate this adaptation of Jeffrey Eugenides’ novel, which is ostensibly about the Lisbson sisters (A.J. Cook, Hanna Hall, Leslie Hayman, Chelse Swain, and Kirsten Dunst) growing up in suburban Michigan during the 1970s?

Mainly because the film is both about the girls being sexually and emotionally oppressed by their mercilessly strict parents (Kathleen Turner and James Woods, both terrifying) and the ways in which they are loved, objectified, and deeply misunderstood by Trip and all the other males in their lives.

All of this is often painful and depressing to watch. Yet “The Virgin Suicides” is also exhilarating, especially during the climactic scene where Trip and a couple of his football teammates squire the Lisbon sisters to a homecoming dance, resulting in a rousing night of driving, drinking, dancing, and finally, Dunst’s Lux and Trip grandly consummating their ongoing flirtation on a football field.

In many ways, it’s all typical movie-teenager fun. Yet that night matters because it’s one of the only times that the girls truly transcend the stifling reign of their parents and the misogyny that surrounds them, before they finally secure a tragic and permanent freedom.

1. Lost in Translation (2003)

A young woman sits by a window. She’s sequestered in her room at the Park Hyatt hotel in Tokyo, and she looks crushingly lonely there. Yet as she stares out at the vastness of the city, the sweet strains of the Squarepusher song “Tommib” caress the moment, tempering her isolation. Don’t give up on her yet, the tune seems to say.

The woman’s name is Charlotte (Scarlett Johansson) and “Lost in Translation” is not just about her—it’s also about a dwindling movie star named Bob Harris (Bill Murray), who has come to Tokyo to star in a whiskey commercial. But most of all, the movie is about him and Charlotte being together, about the passionate friendship they begin one sleepless night at a bar.

Bob and Charlotte’s bond offers an escape from their respective miserable marriages (Bob’s wife, heard only as a cranky voice on the phone, is played by Nancy Steiner, the film’s costume designer; Charlotte’s husband is embodied by a marvelously odious Giovanni Ribisi). Yet it never feels like an affair because the pastimes Bob and Charlotte share—from staying up late watching television to belting out karaoke songs—are disarmingly innocent.

Additionally, Coppola makes it clear that despite the bubbling chemistry between Bob and Charlotte, their relationship isn’t founded on a hunger for the gratification offered by romance or sex—it’s built on purely their compassion for one another.

You feel that whenever they look at each other, you hear it when Bob gently tells Charlotte, “You’re not hopeless,” and you see it in cinematographer Lance Acord’s image of Bob and Charlotte’s reflections in a high-up window, which makes it look as if they’re hovering above the city, borne aloft by their sweet and strange union.

Toward the end of the film, Bob and Charlotte try to wrap up their sexless romance as reunions with their significant others loom. Yet while Bob is being driven back to airport, he spots Charlotte on a crowded sidewalk. So he opens the door, gets out, and does something, something too beautiful to be described, something that says everything you need to know about how much he and Charlotte mean to each other.

That scene arrived ready-made for controversy, due to the mysteriousness of Bob’s now-famous whisper. But that doesn’t matter; it never mattered as much as the fact that “Lost in Translation” is about two people who love each other. That’s what stays with you after the final credits have rolled and after you’ve watched the car carrying Bob resume its path through the city and toward the future.

Author bio: Bennett Campbell Ferguson is a freelance film critic and culture writer based in Portland, Oregon. In addition to reviewing films for Willamette Week, he founded the blog T.H.O. Movie Reviews, which he also edits. You can follow him on Twitter @thobennett.