Now firmly established across the Atlantic, the following years would see Hitch establish himself as a true master of the medium, an auteur easily capable of switching comfortably between genres, from thrillers, to horrors and even comedy, his oeuvre became incredibly consistent and, for the most part, utterly brilliant.

Here, in part two, we tackle the seventeen remaining films that the legendary director produced prior to the end of his exemplary career.

17. Topaz

Like Torn Curtain before it, Topaz was a film that would never have happened had Hitch had his way. He had intended to move onto a project called Kaleidoscope; this was to be a return to more familiar territory for the “Master of Suspense” with its narrative focusing on a male murderer stalking the streets of New York, only to find himself being hunted.

It was apparently set to draw aesthetic inspiration from the films of Michelangelo Antonioni, and Hitchcock had already commissioned the screenplay, location filming and publicity stills when Universal put a stop to the project and had him direct what might very well be the worst film of his career.

Again, like its predecessor, Topaz is a spy thriller, this time based on the popular novel written by Leon Uris with a narrative that concerns Russian spies operating under cover within French Intelligence. The whole affair is played out by straight faced actors who show not one hint of emotion, which is especially concerning given that in the end, the protagonist must fight a man that has slept with his wife.

There was a sizeable budget behind the project, enough to allow some on location filming in Europe, and Hitch used this as an opportunity to avoid interference from the studio, though this meant that he was already shooting the film before the script was even finished. This could certainly be one of the reasons why the final film fell flat, another one ironically, was studio interference.

Hitch altered the ending of the film to deviate from the original macho source material to make comment on the demise of an honour code amongst spies, with the final duel not settled by the better man, but rather the bullet of an unseen sniper.

This, however, did not go down particularly well with preview audiences, fans of the original book or his agent, Lew Wasserman, who managed to threaten Hitch enough that the director reneged on his refusal to make any cuts. He would shoot a further two alternative endings, before ultimately allowing the studio to set to work on the film, making any changes that they saw fit.

16. Torn Curtain

Hitch had originally intended to shoot a film based on the play Mary Rose (written by James M. Barrie), but this was rejected following the failure of Marnie, and he opted instead to make a cold war spy thriller. This film would see the normally prolific director’s malaise continue, as it would for the remainder of the decade.

On paper, it seems like it was destined for success, at least when looking back at it. Unlike the previous two efforts, this one had star power with Paul Newman and Julie Andrews taking on the lead roles, though off-screen there were also changes being made, and not for the better either. For one, Hitch’s regular editor, George Tomasini passed away in 1964 having suffered a fatal heart attack at the age of fifty-five. Elsewhere, Lew Wasserman somehow managed to convince Hitch to part ways with composer Bernard Herrmann in favour of someone deemed to be more contemporary.

Of course, there are issues elsewhere too, Newman, turns in what might be the worst performance of his career, being thoroughly unconvincing in the role of defecting physicist Michael Armstrong. Whilst his love story sub-plot with Andrews is dealt with far too quickly, coming to a resolution somewhere around the halfway mark rather than running side by side with the main narrative, as he had done so successfully in The Birds.

Like Marnie before it, this is particularly disappointing as there is obviously some potential here. Wasserman was looking for Hitch to create a mature alternative to the James Bond flicks that were proving so popular, and with the interesting premise of Armstrong heading to East Germany to steal a formula (for a MacGuffin known as Gamma 5) from Professor Lindt that would render all allied missiles useless, he almost had one.

There is one exceptional moment that really stands out though; Armstrong and a farmer’s daughter kill off the bodyguard assigned to him, but given that neither of them are trained for this, it quickly descends into farce, a calamity of errors.

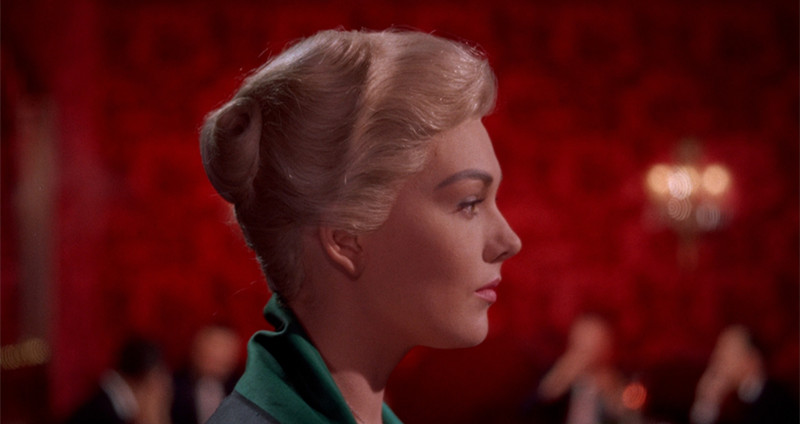

15. Marnie

The lack of star power that plagued The Birds was to prove a major issue here as well, despite the presence of James Bond himself, Sir Sean Connery. Hitch had long been associated with the quality of his leading ladies, now devoid of a genuine starlet, he attempted to create his own with Tippi Hedren.

The pressure that he put on himself to do so led to him placing enormous pressure on her to perform precisely as he instructed, down to the most minute physical movements. He worked her tirelessly throughout the making of the film, driving a wedge between them that would see them not only not work together thereafter, they did not speak again.

Marnie is a film of unfulfilled potential as Truffaut identified in his interviews with Hitch, it’s certainly not without its strengths, but it just doesn’t manage to reach the heights that it seems capable of. The titular role was originally created to lure the Princess of Monaco out of her acting retirement, and it almost worked too, but sadly, following production delays, Grace Kelly was forced to pull out of the project.

There are autobiographical elements that Hitch attributes to the character of Marnie, for one, her roots are not based in the high society backdrop that she resides in through the film. Like the director himself, she stems from less salubrious surroundings and has merely learned to disguise herself as one of the elite. She is also rather frigid and withdrawn, suffering psychotic episodes whenever she sees the colour red, a trait explained later in the film when it is discovered that she killed a sailor when she was just a child – an act that she has yet to recover from.

Connery’s character of Mark Rutland, is also seemingly suffering from some trauma or issues that are never really touched upon, let alone developed, which is a real shame as it might have given Connery something that he could have really sunk his teeth into.

In places it must be said that Tippi Hedren’s performance is outstanding, particularly the last scene that she shares with her on-screen mother (played by Louise Latham) which is rather emotionally affecting. Between this, and some excellent use of the wide screen format (check out the theft sequence in particular), along with a premise that could have really built on his earlier effort, Spellbound, Marnie hints at what might have been. It is, as Truffaut described it, “A masterpiece that has been aborted”.

14. Family Plot

It was widely expected that Frenzy was to be Hitch’s last film, but he had one more surprise in store for his fans, another foray into the realm of the black comedy. Unlike The Trouble With Harry before it, the plot here is actually quite a complex one, yet the film doesn’t suffer too much from this, or the production delays that saw the director do away with his storyboards to effectively work from the seat of his pants as they say, working out sequences on set with his actors, which included a young Bruce Dern among their number.

The main plotline involves the missing heir to a family fortune, crisscrossing its way between two different couples set on a collision course; one, a group of criminals and another who seek a $10,000 reward for finding them. The wayward son, you see, is perhaps more lost than anyone had imagined, having grown into the mould of master crook, this revelation being the source of a great deal of the film’s comedy elements.

Hitch even managed to slip in a reference to his forbidden project, Mary Rose, with Family Plot’s bogus medium (played by Barbara Harris) holding a séance, she later gets to utilise her “powers” at the film’s finale too, declaring the location of a missing diamond. This shot was meant to be the last one of the film, and with it, Hitch’s career, but he called his cast and crew back to the set to add just one final touch, Harris winking knowingly directly into the camera.

This last-minute addition perfectly brought the curtain down a most illustrious career, though if it weren’t for his health being in decline, Hitch would have carried on with his project The Short Night, a script about gangland London assisting a British spy. Alfred Hitchcock officially retired in May 1979, and was later given a knighthood for his exemplary services to film, his lengthy career and consistently strong output have ensured his place as an enduring, and rightfully lauded figure of the seventh art form.

13. I Confess

Transference of guilt is the order of the day again, only this time it’s given a Catholic twist. The film is based on a French play that Hitchcock had sought for years to take to the big screen, and to do this he turned to the playwright, William Archibald, and Catholic writer, Paul Tabori. Much like Under Capricorn before it, the narrative – rather unsurprisingly – deals with the power of confession.

Here, a murder has been committed by Otto Keller (D. E. Hasse) to conceal a theft, he then turns to his church for absolution and confesses his crimes to Father Michael Logan (Montgomery Clift). The murdered man, Villette, as it turns out, knew of a relationship that the priest had with a married woman, Ruth Grandfort (Anne Baxter), and was attempting to use this information to extort money out of him. Ultimately, with a recognised motive, suspicion for the crime falls squarely upon the priest who answers such accusations of guilt with the sacrosanctity of silence as he refuses to defile the sacrament of confession.

For the bulk of the film Clift’s Father Logan is played in absolute silence, with mere looks telling so much of the story and conveying his inner turmoil, this is handled masterfully by the method actor who manages to deliver one of the standout performances of his career. The scene with the priests talking over breakfast is a real highlight as Hitch uses close-ups of Logan and Alma Keller to induce the palpable tension as the accused toils with his heavy burden. L

ikewise, the sequence in the church as the real killer and Logan encounter one another again is simply stellar, not least of which for the superior cinematography and editing, but again in how simple facial expressions from each actor highlights their inner fears before they attempt to cover them up with bravado. Stellar stuff.