American filmmaker Darren Aronofsky has never been the kind of writer-director who shies away from controversial qualities in his films, or to sidestep surreal flourishes as well as story elements that may confound or confuse audience expectations, and his third and arguably most ambitious feature, The Fountain (2006), exemplifies such considerations.

A psychedelic science-fiction fantasy and a historical romance that miraculously maneuvers multiple meanings, ideas, themes, and storylines in an epic triptych that ambitiously spans a thousand years centering on the celestial space pursuance of everlasting life represented in a mythical tree. Sound familiar? Of course not. There’s never been a sci-fi spectacle quite like this.

Starring Hugh Jackman in three roles; as Tomás Verde, a 16th-century Spanish conquistador; Tom Creo a 21st-century neurologist; and Tommy a space traveler in the far future en route to the golden nebula of Xibalba, each fighting to save his beloved (Rachel Weisz) from death, The Fountain takes the biblical tree-of-life from the Book of Genesis and Kabbalah.

There’s also a gripping and speculative through line binding neuroscience and Spanish colonialism as well as Mayan myths glimpsed from an indigenous lens, as well as a playful yet profound intermingling of David Bowie’s “Major Tom” pop chronicle which all earned the film some not unwarranted comparisons to Kubrick’s classic, 2001: A Space Odyssey (1968).

The Fountain, which took over six years to complete, underscores Aronofsky’s gifts as a visionary steward of substantial cinematic head trips that reward patient viewers with a complex, emotional, and deeply rewarding film that will stay with you for some time. And that The Fountain presents a saga-like triptych on the fear of death and dying, it’s certainly a film that will resonate with adventurous and inventive audiences.

The following list seeks to add to the viewer’s experience and understanding of what’s one of Aronofsky’s most personal, imposing, and provocative of films.

6. Matthew Libatique’s stunning cinematography

One of The Fountain’s most immediate pleasures in director of cinematography Matthew Libatique’s dazzling visuals. Libatique, who worked with Aronofsky on numerous creative projects in the 90s, including his directorial feature debut, Pi (1998) and then after that success on 2000’s Requiem for a Dream (in fact they’d continue a semi-regular working relationship also including 2010’s Black Swan and 2014’s Noah).

Certainly Libatique’s creative tack and expert as well as experimental lensing helped bring life to the epic romance with distinct visual cues and looks for each era the story unravels in as well as an often floating camera-feel that helps the ethereal and romantic elements appear more palatable as in the meticulously detailed and beaming bright with candles 16th-century Spanish court ruled by Queen Isabella (Weisz), ruler of Spain; or the darkened yet intricate chambers of the fanatical zealot Grand Inquisitor Silecio (Stephen McHattie) which a gold-lit fringe that dazzles with an Hieronymus Bosch-like lucidity.

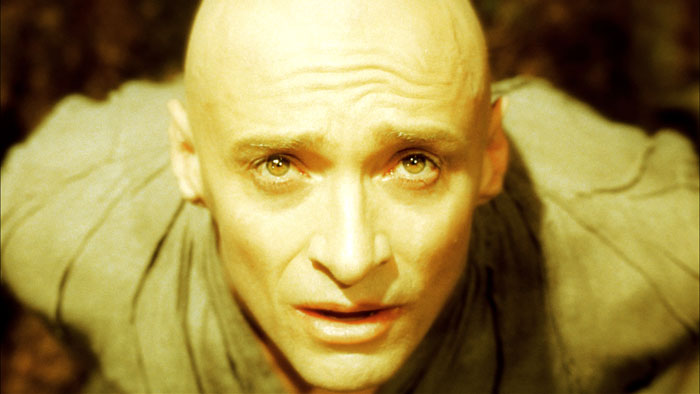

Aronofsky and Libatique also share a fondness and love of close-ups and we repeatedly see sumptuous glances or long and lovely looks of Jackman and Weisz––in proximity that would surely be lauded and loved by the likes of Ingmar Bergman, for one––in cinematic portraiture that smartly underscores the film’s movement from darkness into light.

Regardless of how some viewers might feel about the overall film and some of it’s poetic flourishes and ambiguous angles one point is irrefutable; it looks like a miracle.

5. Peter Parks’ macro-photography

The Fountain was a project plagued with numerous difficulties and a soaring budget. At one point the film was well into principal photography with A-lister Brad Pitt in the lead role(s). When this version of the film was scrapped for numerous reasons, many tied to a ballooning and out-of-control budget, the entire project needed a major rethink in order for it to be saved from the scrapheap.

Part of the solution to revive The Fountain hinged on ways to make it as special effects driven and as filled with psychedelic visuals as Aronofsky envisioned, without incurring a massive cost. Partially for these reasons Aronofsky decided to avoid costly CGI and stick to practical effects and this is where Peter Parks, a macro-photography specialist, enters the picture.

Parks achieved considerable fame using macro-photography to capture deep-sea microorganisms in 3-D while doing research and studies in the Bahamas and he used a similar approach when Aronofsky brought him on board The Fountain, specifically for the portions of the film set in deep space.

Working closely with Aronofsky’s visual effects team of Jeremy Dawson and Dan Schrecker––who shot chemicals and bacteria reacting together that Parks provided, with a wide knowledge of fluid dynamics and other in-camera techniques he’d used with microorganisms. These mysterious looking visuals became the essential and strange elements that surround Tom’s ship as it moves towards its interstellar objective.

“When these images are projected on a big screen,” says Parks, “you feel like you’re looking at infinity… the same forces are at work in the water—gravitational effects, settlement, refractive indices—[that] are happening in outer space.”

4. Gorgeous production design

The Fountain is a grand-scale epic in many respects and part of what struck me when I first saw the film theatrically back in 2006 is how it also cleverly functions as something of a pastiche, at least to my mind, of D. W. Griffith’s towering silent-era narrative Intolerance: Love’s Struggle Throughout the Ages and A Sun-Play of the Ages (1916).

Griffith’s picture, like Aronofsky’s, was first and foremost an art film, and each feature parallel storylines that span the centuries with death and love as dominant themes. Also, both The Fountain and Intolerance feature opulent imagery, with often overpowering and ornat visuals that epitomize the concept of a grand perceptible feast.

In The Fountain the use of art and visual design convincingly recreates the 16th-century, the present day, and 26th-century space travel all with a feeling of profound and proper closeness and veracity.

Aronofsky and Libatique worked closely with production designer James Chinlund––whose many remarkable achievements in The Fountain include a vivid Mayan temple, an ornate Spanish court, and a meticulously detailed neurosurgeon laboratory––to add heightened thematic energy and enhanced visual flash.

For instance, all three creatives agreed upon a limited color palette with added value to the repetitious use of gold and white. The latter bearing much spiritual significance for Weisz’s characters, who are repeatedly in a state of surrender and closest to death.

The art and visual effects department working on the film numbered just over one hundred technicians, all striving for an achieving a mesmerizing and unforgettable look and tactility to, amongst other things, 26th-century space travel, which appears as both awesome and oddly, utterly authentic.

3. The powerful and emotive soundtrack by composer Clint Mansell

Part of what makes The Fountain’s heavy sci-fi and fantasy elements so imaginable and tenable is owed to the virtuoso work composer Clint Mansell, who also wisely chose contributions from first-rate talents Mogwai and the Kronos Quartet.

Today Mansell, an English musician who first came to fame via his influential and excellent 80s and 90s-era alt-rock band Pop Will Eat Itself, is perhaps now best known for his exemplary work doing film scores (Moon, High-Rise, Requiem for a Dream, and Stoker, along with The Fountain, of course, rank amongst his best work).

Just as The Fountain was hugely ambitious and risky for Aronofsky as a filmmaker, so to was it for Mansell in composing its wide-ranging score. He sought to find the most organic and bounded ways to link the three storylines knowing that both orchestral and electronic elements would work best. This is most certainly why post-rockers Mogwai were included in the mix, helping add what Mansell describes as “a real human element that breathes.”

Combined with classical music from Kronos Quartet’s immaculate use of strings and a haunting vocal choir, it’s not surprising that the soundtrack to the film received a wealth of award nominations.

2. The vibrant and powerful performances from Hugh Jackman and Rachel Weisz

It’s unfortunate that The Fountain was met with a great deal of critical confusion and misunderstanding upon its initial release as the entire tightrope act of far flung speculative fiction is given so much veracity and verve from it’s two outstanding leads. First and foremost is Hugh Jackman in three disparate roles that each display a vulnerability and a humanity that is so rare in a mainstream motion picture.

“It’s rare you see a man cry on film, especially a man cry over love. It’s a shame that type of sentimentality isn’t represented in film. I think it turns some people off. A lot of women told me they had never seen a man cry like that before and didn’t know how to handle it.”

– Darren Aronofsky

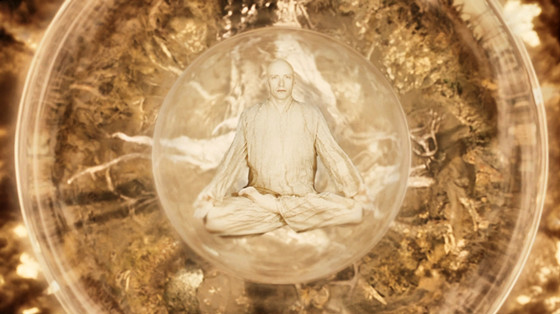

Whether Jackman is the Spanish conquistador Tomás Verde, sent to the New World by the queen of Spain to locate the biblical tree of life, ambitious and distracted neurologist Tom Creo bent on curing his wife’s terminal cancer, or enlightened, meditative, and guru-like space traveller Tommy (yes, his name is a deliberate reference to Bowie’s “Space Oddity” superhero Major Tom), his flawed but impassioned characters are wholly believable and entirely sympathetic.

In fact, in the latter storyline where a 30-second sequence shows Tommy gracefully and naturally assume the lotus position while in his space bubble was the result of Jackman training in t’ai chi for some seven months.

“Filmmaking is an exercise in paranoia. When one writes, the goal to relate every scene to your main character, to your theme. That’s exactly how paranoid schizophrenics look at the world. They believe everything in the universe revolves around them. So in effect, all characters in a film would only be truly conscious if they were paranoid.”

– Darren Aronofsky

While it is terribly tragic that the obsessive and preoccupied Tom shrugs off Izzi’s many attempts to connect and be in the moment with her during her final, fleeting days and moments, it elevates the emotional investment the audience has for the tragedy that we, unlike Tom, can see coming unavoidably right at us.

Izzi’s grace and acceptance in the face of annihilation is also incredibly authentic feeling, and demonstrably stirring. In preparing for her role, Weisz spent time in hospice care facilities where she visited with young people who were dying, in addition to all the more traditional research and prep that serious actors would undertake. But the time Weisz spent amongst dying people certainly gave Izzi that dignity and refinement that makes her passing so much more moving and poignant.

Both Jackman and Weisz are perfectly cast in The Fountain, and their commitment to the film, each other, and the audience, provide much of the intensity and enlightenment that’s crucial to the film’s success and sustain.

1. In Aronofsky’s own words

“[The Fountain] was the film I wanted to make. Of all my movies, to the people that are fans, it’s almost like a cult religion, they get tattoos and I’m constantly getting long letters from people saying it helped them come to terms with something. So I think it works for a much smaller audience because ultimately the film is about coming to terms with your own death, which is not a big commercial idea for a lot of people… “

“The way we treat old people and people who are dying is just… with all our advances in science we’ve just become incredibly cruel with how the end of life is dealt with—especially in the States, it’s really messed up. And the beginning of life too—giving birth in America you have to do it in a hospital and there are very few options for natural childbirth. So Western science has taken control of the way we are born and the way we die, and there’s really no spirituality to it any more. This is why [The Fountain] wasn’t a commercial movie.”

– Darren Aronofsky

Author Bio: Shane Scott-Travis is a film critic, screenwriter, comic book author/illustrator and cineaste. Currently residing in Vancouver, Canada, Shane can often be found at the cinema, the dog park, or off in a corner someplace, paraphrasing Groucho Marx. Follow Shane on Twitter @ShaneScottravis.