During a drive from Chicago to Los Angeles, Jonathan Nolan told his brother, Christopher, about a story he was working on—a story that would change both of their lives. It was a tale of vengeance shadowed by loss: The saga of a man incapable of making new memories hunting for the criminal who murdered his wife.

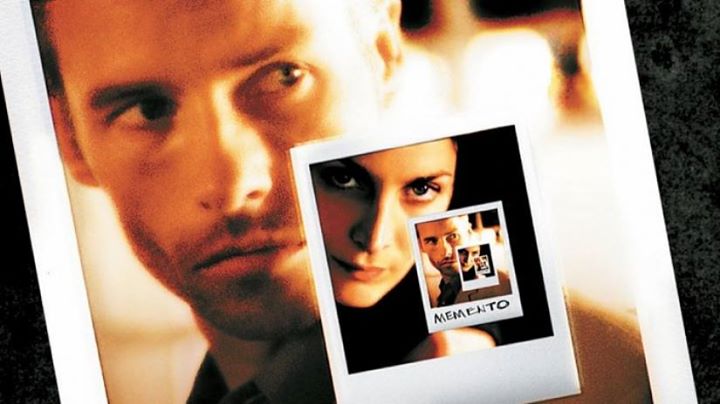

Jonathan’s story (which was published in Esquire under the title “Memento Mori”) got his brother’s attention. Not only that, but Christopher ultimately adapted the concept for the screen as “Memento,” a Southern California neo-noir that received two Oscar nominations (for Christopher’s script and Dody Dorn’s editing) and became famous for its audacious backwards narrative (which begins with its protagonist, Leonard Shelby, played by Guy Pearce, completing his bloody-hearted mission, then doubles back to dissect the events that lead up to the kill).

“Memento” was released domestically in 2001 and in the years since, both Christopher’s and Jonathan’s stock in the entertainment industry has gone stratospheric (as writers, the brothers collaborated on several of Christopher’s films, including “The Dark Knight,” “Interstellar,” and “The Prestige”). Yet despite the increasingly flashy achievements of both men, “Memento” remains a milestone in their respective careers—for the following six reasons and beyond.

1. Its backwards narrative captures its protagonist’s fractured state of mind

In our current era of suffocating Marvel bombast, it’s almost unbelievable that a film as unconventional as “Memento” was ever greenlit. Yes, Christopher Nolan quickly proved himself with the masterfully menacing “Following,” but the idea of making a film that opens with an ending and closes with an opening must have seemed daunting. After all, emotions are linear by nature; at the time, how could audiences have been expected to invest in a film filled with feelings that coursed like a river backpedaling against its own current?

Very easily, it turns out. While you’d think the reversed chronology of “Memento” would keep moviegoers at an emotional distance, having to watch each scene without knowing what occurred before it actually draws you close to Leonard by forcing you to feel the same frenzied paranoia and general discombobulation that he experiences. You may be confused, for instance, when the movie abruptly cuts to a frenzied chase where Leonard runs from a man with a gun, but that’s exactly the point, since Leonard doesn’t know what’s going on any more than you do.

2. It’s a whodunit with a moral dimension

The name “John G.” wafts through “Memento” like the scent of a burning corpse, and it should: It’s the only identification Leonard has for the man who murdered and raped his wife (Jorja Fox). But while most directors would have waited till the film’s end to reveal John G., Nolan chose to begin “Memento” with Leonard shooting and killing Teddy (Joe Pantoliano), the cop he believes to be John in disguise. Thus, “Memento” becomes not a quest for revenge, but a quest for the knowledge of whether or not Leonard killed the right man.

That mystery makes “Memento” fascinating both narratively and morally. In storytelling terms, it allows us to make sense of Nolan’s reversed chronology—even though we don’t witness the events of Leonard’s life in chronological order, the film still progress in a fairly straight line from a question to an answer (there is a secret in Leonard’s past, in turns out, that is the key to ascertaining Teddy’s guilt or innocence).

And on moral grounds, trying to decide whether Teddy is guilty molds what might have been an assembly line story of vengeance into a more nuanced film that asks not only whether Teddy’s fate was just, but whether revenge is ever just.

3. It’s a crowd-pleasing thriller

While Christopher Nolan’s work is often discussed in maddeningly pretentious terms, his films are anything but. They may be brainy, but they also throb with adrenaline and usually include a heroic, applause-worthy triumph, like Christian Bale making a leap for freedom as he escapes the gaping prison pit that nearly swallows him whole in “The Dark Knight Rises.”

Needless to say, the grief-soaked “Memento” is a far more pessimistic work than that bellowing summer blockbuster. Yet it’s also a crowd-pleaser in its own right because despite its modest budget, it’s packed with flourishes of theatricality that make it not so different from the darkly giddy reinterpretation of Batman that Nolan and Bale engineered with “Rises” and their other “Dark Knight” films.

Like that flamboyant superhero saga, “Memento” boasts a bevy of crowd-pleasing elements. It features an alluring, multifaceted femme fatale (Carrie-Anne Moss’ sneaky Natalie), a romantic quest (there’s an intoxicating glamour to the image of the impeccably dressed Leonard hunting for the slayer of a gorgeous woman), and a hairpin twist that does not much pull the rug out from under your feet as cause your brain to momentarily leap out of your skull.

Which, painful-sounding metaphors aside, is a pleasurable experience. Because while the themes of “Memento”—existential confusion, grief, rage—are heavy, they are also part of a carefully wrought puzzle narrative whose knotted intricacies dare us to take up the challenge of working them out. Which makes “Memento,” in the best way possible, the cinematic version of a night of Scrabble or Clue.

4. Nolan’s clever use of visual clues enriches the movie’s narrative

From a very incriminating hammer in “Following” to that meddlesome spinning top in “Inception,” Nolan has always had a knack for filling his movies with objects that tell stories. It’s a creative fetish of sorts and in “Memento,” it manifested in an intriguing set of clues: the wordy tattoos that Leonard uses as his life guide.

The most memorable of the mantras engraved in Leonard’s flesh is, “JOHN G. RAPED AND MURDERED MY WIFE,” which is burned into his chest. It’s a constant reminder of his quest for vengeance, though it’s also hints at Leonard’s fallibility in a chilling fashion. Because while he assumes that the tattoo is based on truth, how can he know? What if it was a prank? What if he was never married? Nolan’s point is that there’s no way to be sure and that the faith Leonard and humans in general put in physical evidence is radically misguided.

For Nolan, such clues are also tools for generating sharp pricks of suspense—as evidenced by the moment when Leonard, while talking on the phone, realizes that he has a tattoo that reads, “NEVER ANSWER THE PHONE.” As we read those words, we’re instantly plunged into a maelstrom of intoxicating uncertainty (is the guy he’s talking to on the phone a threat?). The unknown, it turns out, is not just the intellectual terrain “Memento” explores: It’s another reason why the movie is fun to watch.

5. Guy Pearce’s performance brings humanity to the film’s esoteric story

If you want a clear illustration of Nolan’s evolution as both a storyteller and a humanist, try contrasting “Memento” with “Interstellar,” his tear-stained 2014 space odyssey. In both films, a man attempts to complete a mission in the name of someone he loves, but there’s a crucial difference: In “Memento,” Leonard’s wife is seen only in vague, fleeting flashbacks, whereas Murph—the daughter of Matthew McConaughey’s zealous astronaut in “Interstellar”—is imbued with vivid, emotionally textured life by the gifted young actress Mackenzie Foy (as well as by Jessica Chastain and Ellen Burstyn, who play the character as an adult).

To put it more bluntly: Murph is a human being and Leonard’s wife is a storytelling device. To Nolan, she apparently matters only because her death fuels Leonard’s macabre journey, which likely contributed to the director’s reputation as a head-over-heart filmmaker (a reputation he refuted beautifully with swelling, unbridled emotions of not only “Interstellar,” but “Inception,” and the “Dark Knight” trilogy).

All of which placed an unfair burden onto Pearce’s shoulders. Since Leonard’s wife is a non-entity (unlike Marion Cotillard’s slain spouse in “Inception,” whose specter is a constant, haunting presence), Pearce had to convey the weight of grief with—arguably—little help from Nolan.

And while it was a momentous task, he makes you see Leonard not only as a hunter, but as a widower, especially during a wrenching interlude where Leonard burns some of his wife’s belongings and declares, “Can’t remember to forget you.” It’s a great line, but it’s still not as great as the image of Pearce’s anguished face illuminated in the flickering light of the flames, reminding us of the loss that lurks behind Leonard’s rage.

6. It brilliantly deconstructs the concept of revenge

WARNING: SPOILERS AHEAD.

Is “Memento” a revenge thriller? Superficially, yes. But dig beneath the movie’s embittered surface and you’ll find something more: an anguished, wise, and deeply unsettling moral tale that fills the phrase, “An eye for an eye makes the whole world blind,” with fresh urgency.

That urgency begins to percolate during the film’s unnerving final sequence, in which Teddy reveals a secret that undermines Leonard’s entire existence: That Leonard’s wife was raped, but not murdered (Teddy also claims that she was diabetic and that she died because Leonard gave her an insulin overdose). Teddy then explains that when hunting down and killing the rapist didn’t satisfy Leonard, he allowed Leonard to believe that the attacker was still at large so he wouldn’t have to relinquish the thrill his quest for vengeance.

Naturally, Leonard rejects this explanation. But Teddy remains adamant and even says that Leonard himself is complicit in the deception and has hidden information from himself in order to prolong the chase. Enraged, Leonard storms away and plants evidence that Teddy is the attacker, thus giving himself a new target to track down and revealing that in the film’s first (last?) scene, he did in fact kill the wrong man.

Or did he? Given that Teddy could easily dupe a man in Leonard’s condition, it’s possible that his story is designed to cover his tracks. But if it’s the truth, Leonard’s entire journey is a sham meant to stave off his grief and burnish his ego.“You’re living a dream, kid” Teddy tells Leonard, playing on our suspicion that Leonard’s manly seething over the loss of his wife is based not only in grief, but in a desire to imbue his pained existence with a self-serving, tragically noble romanticism.

Which is Nolan’s way of reminding us that the heady thrill of retribution is always too good to be true. You could call that hypocrisy (since “Memento” mines Leonard’s hunt for joyous suspense), but that doesn’t mitigate the horror of watching Leonard drive away from Teddy, embracing a journey that’s chillingly devoid of a righteous purpose. “I have to believe my actions still have meaning, even if I can’t remember them,” Leonard tells us. But the tragedy of his life is that has no meaning because despite what he has chosen to believe, he exists to help only one person: himself.

Author bio: Bennett Campbell Ferguson is a freelance film critic and culture writer based in Portland, Oregon. In addition to reviewing films for Willamette Week, he founded the blog T.H.O. Movie Reviews, which he also edits.