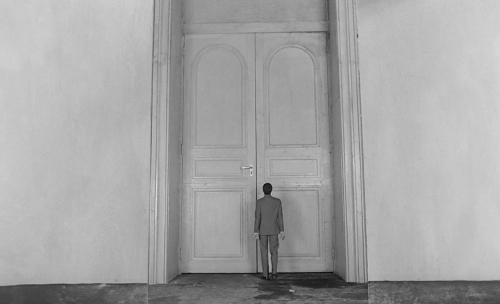

“Before the law, there stands a guard. A man comes from the country, begging admittance to the law. But the guard cannot admit him. May he hope to enter at a later time? That is possible, said the guard. The man tries to peer through the entrance. He’d been taught that the law was to be accessible to every man. “Do not attempt to enter without my permission”, says the guard. I am very powerful. Yet I am the least of all the guards. From hall to hall, door after door, each guard is more powerful than the last. By the guard’s permission, the man sits by the side of the door, and there he waits. For years, he waits. Everything he has, he gives away in the hope of bribing the guard, who never fails to say to him “I take what you give me only so that you will not feel that you left something undone.” Keeping his watch during the long years, the man has come to know even the fleas on the guard’s fur collar. Growing childish in old age, he begs the fleas to persuade the guard to change his mind and allow him to enter. His sight has dimmed, but in the darkness, he perceives a radiance streaming immortally from the door of the law. And now, before he dies, all he’s experienced condenses into one question, a question he’s never asked. He beckons the guard. Says the guard, “You are insatiable! What is it now?” Says the man, “Every man strives to attain the law. How is it then that in all these years, no one else has ever come here, seeking admittance?” His hearing has failed, so the guard yells into his ear. “Nobody else but you could ever have obtained admittance. No one else could enter this door! This door was intended only for you! And now, I’m going to close it.” This tale is told during the story called “The Trial”. It’s been said that the logic of this story is the logic of a dream…a nightmare.”

– Opening fable of “The Trial”

Orson Welles, to many the only true aristocrat amidst Hollywood royalty, was the owner of excessive personality at times unstable, conflicting, at others, brilliant, unmoved. Yet capable of producing the most original of films, aesthetically and formally speaking. He was dubbed a man ahead of his time, title that is justifiable by many facts of Orson Welles life such as: travelling across Dublin, with a donkey and a cart, while struggling to be a painter; producing a radio show that made half America believe the country was under alien invasion; writing-directing-producing-starring in the ‘greatest film of all time’ whose repercussions and influences can still be felt today; entering in ugly disputes with major film studios; being fired multiple times; shooting films around the world often backed up by broke producers; meeting illustrious people like Winston Churchill or Franklin D. Roosevelt; adapting Shakespeare; producing a half circus half magic show to entertain soldiers as part of the war effort (“The Mercury Wonder Show” in 1943); producing a musical that led to his own bankruptcy (“Around the World” in 1946) and the list goes on and on.

In conclusion, Orson Welles was a remarkable individual who led a life full of drama, of bad luck, of love, of greatness, of tragedy which ultimately is mirrored one way or another in the films he directed.

His first feature film was “Citizen Kane” which despite the heavy studio imposed cuts and the bad publicity spread by the Hearst press, is still considered a major landmark in film history. Followed by “The Magnificent Ambersons” another studio controlled picture, on which only a portion of Orson Welles vision still lives. After an almost five-year absence, the director’s last presences within the studio system were “The Stranger” (1946) and “The Lady from Shanghai” (1947), interesting pieces whose lost value is due to their fall under some of the studio system conventions.

However, once Orson Welles travelled to Europe (where he shot in multiple countries even extending himself into the northern African coast) he was able to gather – amidst several difficulties – backing from various sources to work on three Shakespearean adaptations: “Macbeth” (1948), “Othello” (1951), “Chimes at Midnight” (1965).

During the preparation of these films and in the years between them, Welles participated in a number of TV contents, as a director or producer, as an actor or as himself. He also acted in other people’s films and returned to America to direct “Touch of Evil” which he only did because Charlton Heston misunderstood in a call from the studio that Welles was the director to which he replied “I’ll act in anything Orson Welles directs”.

Still during the 1960s Welles notoriously directed “The Trial” (1962) and for TV “The Immortal Story” (1968) and “The Merchant of Venice” (1969). In the 1970s, “The Deep” (1970) and “F for Fake” (1973), were his most successful achievements.

He died in 1985 leaving behind a number of unfinished projects, inspiring concepts and numerous ideas for films. His last projects were the short film “The Spirit of Charles Lindbergh” in 1984 and the television special “Orson Welles’ Magic Show” which was being filmed since 1976.

However, this article’s subject is “The Trial”.

“‘The Trial’ began as ‘Taras Bulba’. I did a one-day job for Abel Gance in ‘Austerlitz’, which was produced by a couple of Russians named Salkind – father and son. And they came to me a couple of years later and said they wanted me to act in ‘Taras Bulba’. Now, at that same time, an American company was about to shoot a ‘Taras Bulba’ with Yul Brynner and Tony Curtis, and I said, well we’re going to have trouble fighting that big, expensive American picture. They said, we’re willing to go ahead. So, I said, I’ll only do it if you let me direct it and write it. They said all right. So, I wrote a script for ‘Taras Bulba’ – the real one – because it’s a wonderful story, and when I’d finished, I went to see them and they said Well, we decided you’re right. The Americans are nice. So, I was stuck with the script of ‘Taras Bulba’ – but now I had what was called a relationship with them. And the old man, who had made Garbo’s first picture out of Sweden – an angelic, dear man – gave me a list of about a hundred books, saying, which one did I want to make? They had Kafka’s ‘The Trial’ on the list, and I said I wanted to do ‘The Castle’ because I liked it better, but they persuaded me to do The Trial. I had to do a book – couldn’t make them do an original.”

– Orson Welles in “This is Orson Welles”.

Produced in 1962 and shot across the streets of Zagreb and in the Gare d’orsay in Paris, the film stars Anthony Perkins as Josef K., Jeanne Moreau as Marika, Romy Schneider as Leni, Akim Tamiroff as Bloch and Orson Welles himself as the Advocate.

It tells the story of a man named Josef K. who awakens one day to a living nightmare as his bedroom is invaded by several detectives who arrest him, however, either reasons or charges remain unknown to him. Desperate, K. seeks the help of many people, among them is a powerful and influential figure, the advocate, as well as, an artist by the name of Titorelli.

When released the film faced great criticism particularly from America but also from European countries with a major film market – exception made to France. However, to all those voices, Welles gave only an answer: “Say what you like, but ‘The Trial’ is the best film I have ever made”. And it is the purpose of this article to state some of the reasons that validate Welles’ opinion as to why “The Trial”, undeniably, still remains one of his best works.

1. More than an adaptation, it is really a theme-based and personal film

A lot of people dismiss “The Trial” because they feel it’s not Kafka and some others dismiss “The Trial” and its importance because they feel is not Orson Welles’. Well, to the first the answer is quite simple: an adaptation is not made into screen word by word as it is written in the book or another literary source. Adaptation is called to something that results from the vision of the source plus the vision of who is adapting it, otherwise it wouldn’t be an adaptation but rather a copy.

Thus, what Orson Welles did was to use Kafka’s moulds for people, sets and atmosphere which he fulfilled with his own ideas, desires, fears, therefore turning the film into something he defends and esteems “I suppose because it’s my own picture, unspoiled in the cutting or in anything else.”

And that is also the answer to those who dismiss the film because it doesn’t feel Orson Welles – how can you define what is an Orson Welles film if from “Citizen Kane” produced in 1941 to “The Trial” produced twenty-one years later all of his films where either severely cut, had parts reshoot and inserts from other directors?

Franz Kafka published his novel in Prague somewhere around 1925 and some people view this event as a prophetic one of what would happen to Jews in the 1930s and during WWII, a time when entire families were shut down in ghettos, driven apart from each other and sometimes woke up, just like K, with German officers in their houses arresting them. For what? For being themselves. Jews.

However, people tend to forget that anti-Semitic ideas have been around even before those events. For instance, in the beginning of the twentieth century, Jewish migration to America led to an uprising of anti-Semitic ideas in that country which culminated with the notorious lynching of Leo Frank – who had been accused of murdering Mary Phagan in 1913 – in Georgia around 1915. In the same year of Leo Frank’s accusation, a similar case happened in Europe (Kiev, part of the Russian Empire), a Jew by the name of Menahem Mendel Beilis was also accused of murdering a 13-year-old child and this case too became notorious for its spread of anti-Semitic ideas.

So, Kafka’s work can naturally be viewed as a reaction against these contemporary anti-Semitic events and the spread of anti-Semitic ideas. Thus, harassment, persecution and paranoia can be viewed as the main themes in Kafka’s “The Trial” either by others exterior to K, either by K to his own repressed self.

When it comes to Orson Welles adaptation of “The Trial” we have naturally to add the director’s own personal experience as he puts it:

What made it possible for me to make the picture is that I’ve had recurring nightmares of guilt all my life: I’m in prison and I don’t know why, going to be tried and don’t know why. It’s very personal for me. A very personal expression, and it’s not at all true that I’m off in some foreign world that has no application to myself; it’s the most autobiographical movie that I’ve ever made, the only one that’s really close to me (…) It’s much closer to my own feelings about everything than any other picture I’ve ever made.

So, to the novel’s harassment, persecution and paranoia ideas another theme should be added – guilt; perhaps that is why the advocate’s house and about all the sets in the film gain a sort of labyrinthic dimension and the advocate himself is this mighty powerful figure, sort of like God. It’s like Kafka conceived a world and an atmosphere in which he reflects life itself (with his and the world’s paranoias), while Orson Welles conceived a more introspective world based on a sort of afterlife dimension. Just a thought.

2. It is an experience (dreamy mood)

One of the major qualities of Orson Welles’ “The Trial” is the capacity of maintaining a dreamy mood throughout the film which is something that increases the film’s importance because it becomes rather an experience that just film as art or film as entertainment.

It’s a dream.

– And dreams aren’t specific.

Well, they can be specific, but some aren’t, and this wasn’t because it’s the very formless that is the horror of that story. It is supposed to project a feeling of formless anguish, and anguish is a kind of dream which makes you wake up sweating and whining. That’s what that’s supposed to do, and that’s all. It’s an experience. (…) It’s full of passion – human stuff. I’m not coldly spooking you. But, of course, it’s an icy atmosphere. Dank, horrible atmosphere. And the eroticism is dirty and morbid.

Like Orson Welles states, the film’s idea is not to cause fright but to induce us in a long continuous nightmare. And something that works in this favour is what can be called the ‘exchange of viewpoints’ that is made so cleverly throughout the film.

‘Exchange of viewpoints’ means that at a given moment in the film, we, audience, see things through the eyes of Josef K, therefore, we, audience, are reduced to the lonely figure of K and once we start to feel as imprisoned and as paranoiac as he is, a cut happens and we, audience, are put in an observant position just like an invisible third party who watches impotently to the injustices suffered by K.

And by playing with this element the director effectively approximates the audience to K to such an extent that even in open air, for instance, when K runs around wider spaces, we feel almost as trapped as he is.