With the heritage of 1990s riots opposing police brutality and the inequality between race and class alike still very much alive, perhaps it is shameful that the controversial issues raised in La haine remain as relevant as they are. With the title derived from the phrase in the film: “Hate breeds hated” (“La haine attire la haine”), La haine is not only shockingly relevant in modern society, but in modern cinema as well.

La haine remains a renowned and significant example of modern French film, primarily for two related reasons: Firstly because it manages to perfectly capture the state of contemporary French cinema, whilst secondly expertly portraying the state of contemporary French society.

Furthermore, La haine also opened filmgoers’ eyes to a France unknown to many cinéphiles the world over while addressing social injustices and cunningly reversing age-old damaging stereotypes.

Finally, upon its release the film provided a new lease on life for French filmmakers with its fresh new aesthetic and the urgent pertinence of its subject matter. Here are five elaborations on why La haine is the most important film in modern French cinema:

1. American Influence on the Film and Culture

Regarding the state of French cinema at the time of the film’s release, director Mathieu Kassovitz remarked on the commentary track of La haine that the that the once-innovative French New Wave had become harmful to the evolution of French cinema in the 1980s. Interestingly, both La nouvelle vague and La haine drew inspiration from the same source; American cinema.

While the band of cinéphiles that pioneered the French New Wave found immense artistic value in the auteur cinema of the likes of Howard Hawks and Nicholas Ray, Kassovitz visibly borrows and pays homage to tropes of New Hollywood cinema—most notably Martin Scorsese’s Mean Streets—and contemporary hip-hop culture of 1970s and 1980s America.

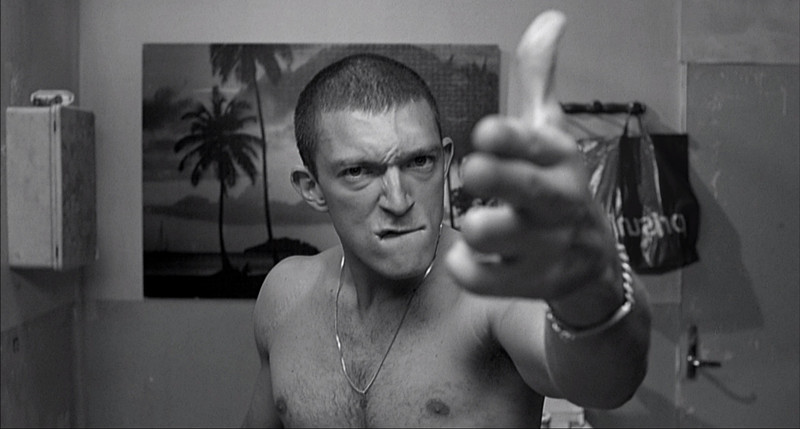

There are two scenes in particular that showcase the uniquely Franco-American spirit of the film, starting with the scene where protagonist Vinz postures aggressively in front of his bathroom mirror, aping Robert De Niro’s iconic “You talkin’ to me?” monologue from Martin Scorsese’s Taxi Driver. What makes this sequence remarkable is Vinz’s Gallic appropriation of this classic morsel of American pop culture, translating the phrase into a very informal French “c’est à moi qu’tu parles!?”

The second scene features a cameo by DJ Cut Killer, playing a mix of KRS-One’s “Sound of da Police”, interspersed snippets of French hip-hop artists Assassin and Suprême NTM with the declaration “Nique la police” (“Fuck the police”), as well as samples of Édith Piaf’s “Non, je ne regrette rien”. This eclectic blend illustrates a clash between the classic idea of French cultural identity of yesteryear and the harsher, americanized reality of modern France.

Another trait lifted from American cinema of the era is the film’s “life in a day” structure also seen in features such as Spike Lee’s Do the Right Thing and Kevin Smith’s Clerks (another black and white film coincidently); both films that deal with issues of racial tension and adolescent ennui, respectively.

2. A France Unseen

For decades, the global perception of French cinema was dominated by Gallic stereotypes of bourgeois-bohème Parisians, navel-gazing against the backdrop of the Champs-Élysées or a well-to-do café. La haine transports viewers from a familiar and luxurious Paris to its banlieues—suburbs, marked by housing projects and urban decay.

Early in the film when Saïd stands in front of the complex wherein Vinz resides, we’re shown dozens of apartments crammed and stacked claustrophobically together, the residents practically spilling out the windows to complain about the noise. The surrounding neighbourhood is a veritable assortment of vandalized concrete structures, deserted buildings and burnt shells of cars; far from the café society imagery international filmgoers had been fed on for years.

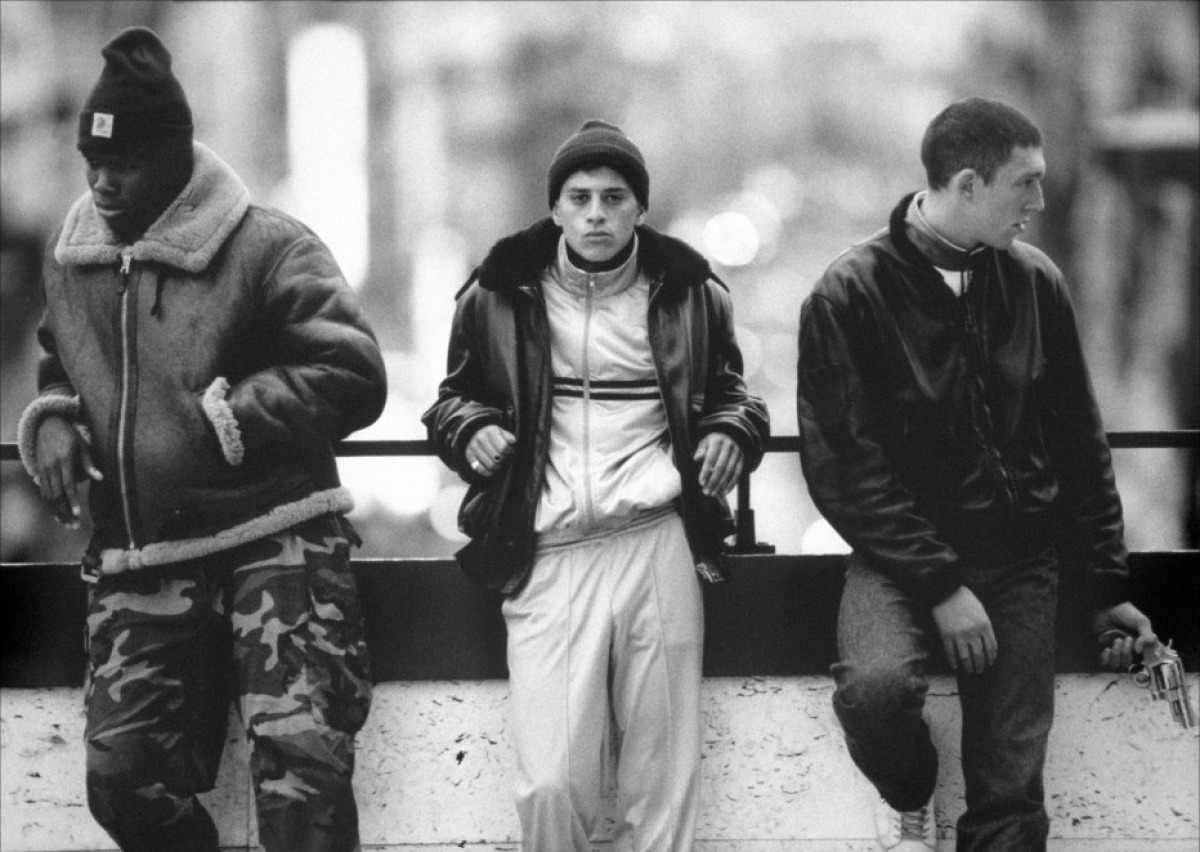

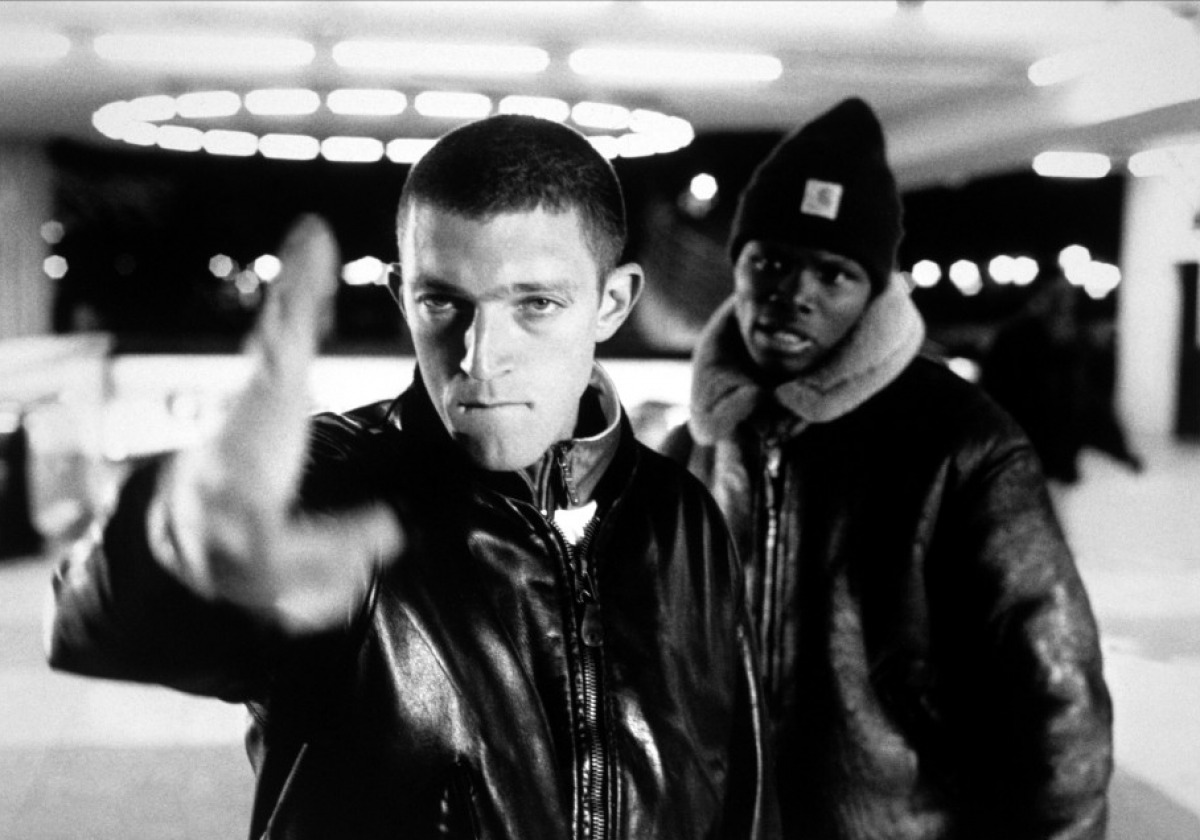

In terms of the cast, the three protagonists are all minority groups in French society. Saïd is an Arab Maghrebi, Hubert is Afro-French, and Vinz is Jewish. The documentation of their unique experience in what is essentially their country as much as it is any other French citizen’s is a crucial element in the film as they face adversity not only from police but from the manipulative media and far-right thugs as well.

3. Reversal of Stereotypes

The use of a multicultural minority cast allows for the film to address certain harmful stereotypes. Saïd and Hubert, both of African origin, would be considered outsiders in the group and—in the eyes of right-wing xenophobes—problematic to French society.

However, Saïd is probably the most harmless, naive member of the trio; whereas Hubert is the most devotedly pacifist, with a clear moral code. Inversely, the Jewish Vinz defies the inflammatory stereotype of meekness and submissiveness by being the most volatile and arrogant of his friends.

A recurring theme with the character of Vinz is that while Caucasian are the most accepted into traditional French society among his friends, he feels especially disenfranchised. Although he has twice the privilege of his friends, this privilege is matched with unwarranted petulance and indignation.

Caught between two societies—that of the traditional, privileged French class and that of his friends who find themselves abandoned by this outdated definition—Vinz at one point makes a very telling remark where he asks Saïd if he wants to be the next Arab to be killed in a police station.

When Saïd says no, Vinz replies “me either”. Here we see him struggling to find his place on his marginalized friends’ side of the battle, and outdoing them in the process by plotting to kill a cop pending the death of their friend Abdel.

It could be said that as a young Jewish man, Vinz was raised on a heritage wrought with trials, tribulations and pronounced suffering, but he himself feels no connection to the persecution of his ancestors and seeks to align himself with it and channel his vengeful sentiments by putting himself in the shoes of the people currently marginalized the most in France; his foreign comrades.

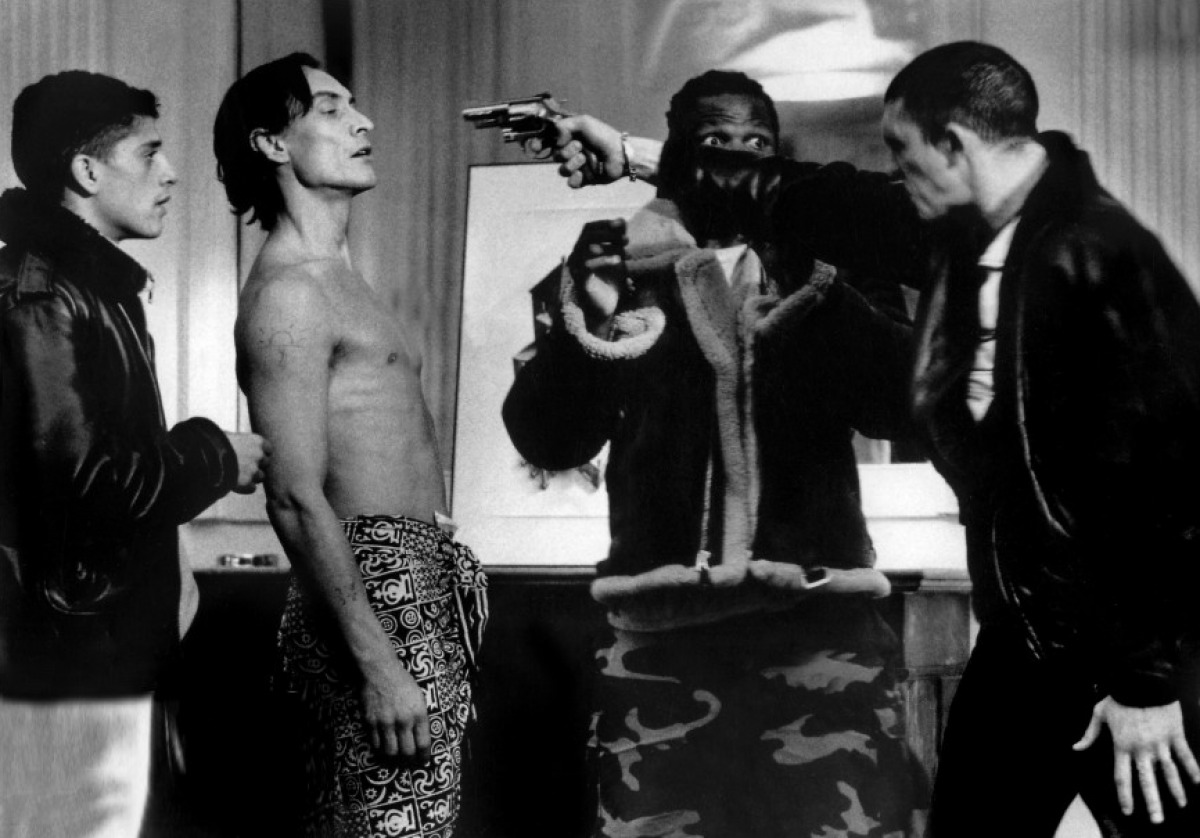

Towards the end we see that Vinz’s volatile personality was but a facade, and when he attempts to assassinate a lowly skinhead he fails, sickened by the prospect. This, coupled with his decision to turn his revolver over to Hubert, is a clear indication of his realisation that he does not have the stake in the conflict he claimed to have.

4. Addressing Controversial Social Issues:

In La haine there is a quote, recited by Hubert, which serves as a bookend for the film:

It’s the story of a man who falls from a 50-storey building. As he falls, he repeats over and over to reassure himself: “So far so good, so far so good, so far so good.” But it’s not the fall that’s important – it’s the landing.

At the film’s conclusion the quote is revised to refer more specifically to a society that is in the same state of freefall as the man in the original analogy. The intention of the film is to portray the breaking point of a flawed system; an ultimate destination if things continue along their current trajectory.

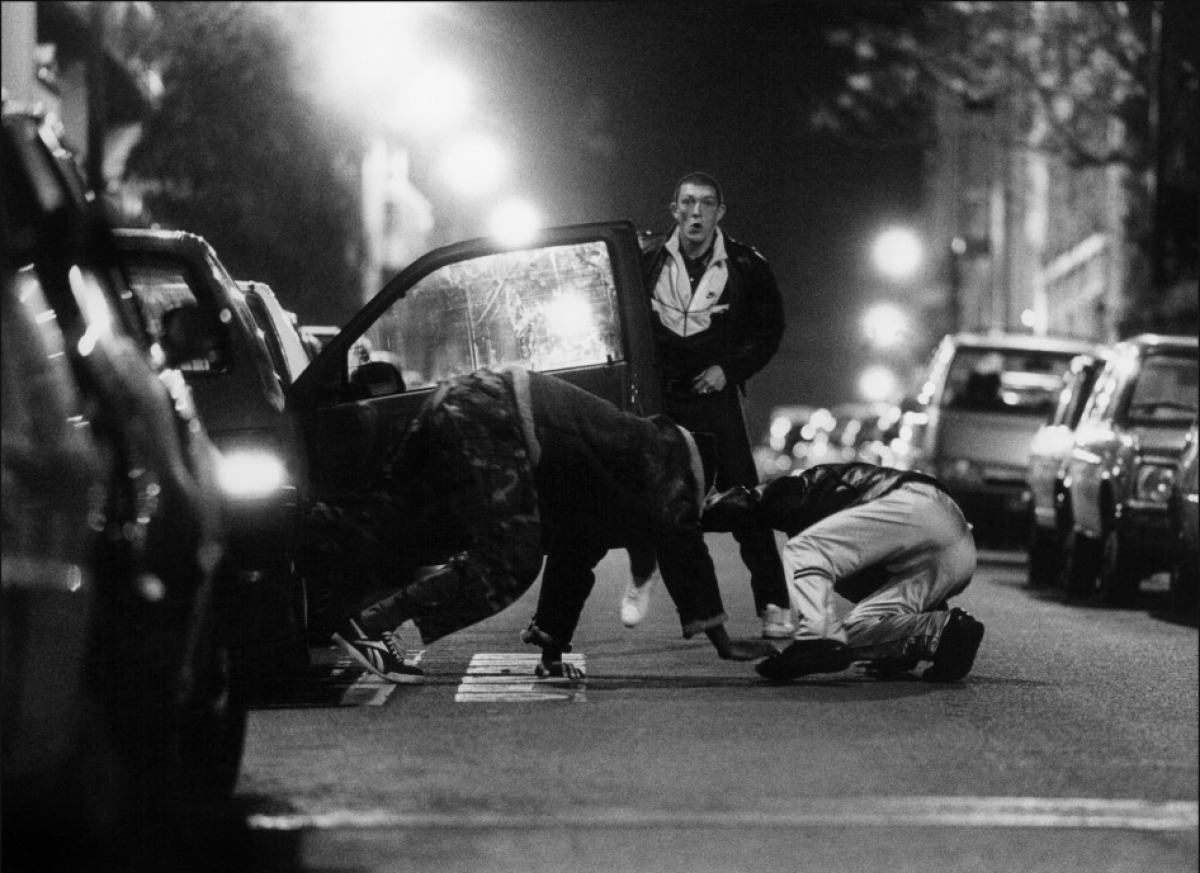

La haine makes no effort to soften the urgency of the poverty and desperation experienced by the characters. Trapped by their surroundings, their existence is reduced to loitering, drug deals and reckless thrill-seeking.

Although the riots in the banlieues are rooted in a protest against what is perceived to be unjust behavior on the part of the police, the only clear result they are producing is more police brutality and the thoughtless destruction of their own environment. Their friend laments the senseless destruction of his car, and Hubert suffers the loss of the boxing gym, but nothing is resolved.

It seems at times their existence in these ghettos is so nihilistic that the characters are merely passing the time until they themselves ultimately succumb to either their own environment or a provoked police officer.

Police corruption and brutality is another controversial topic the film refuses to shy away from. The brutal assault and eventual death of Abdel, the young Arab man and friend of the trio, as well as a misplaced service revolver found by Vinz amidst the rioting serve as a backdrop for the film’s events.

Throughout the day, Vinz, clearly more incensed than his more at-risk comrades, claims that if Abdel succumbs to his injuries… he would use the gun kill a cop in retaliation. The issue of police brutality was extremely pertinent at the time of the film’s release, with the character and story of Abdel being influenced by the questionable deaths of two young French-African men at the hands of police. Ultimately, after coming to terms with his inability to take a life, it is Vinz himself who is killed by police in a careless accident.

5. Lasting Influence

For better or for worse, La haine—alongside other French films such as the directorial efforts of Luc Besson—gave birth to a new niche in French cinema that was marked by its blend of grittiness, classic American cool and explosive visual style that was destined to turn heads on a global scale.

In France, an almost immediate successor to La haine’s gritty social consciousness and hip-hop aesthetic was the film Ma 6-T va crack-er (Ma cité va craquer), released in 1997.

One of the more recent examples of La haine’s cinematic legacy in France is the prison drama Un prophète; which documents a young French-Algerian’s ascent through the ranks of organized crime within the prison system.

The film’s stripped down nature as well as its frank and brutal portrayal of prison life and corruption makes it clear where its cinematic influences lie. Other, more international examples of films dealing with social desperation and racial tensions in the same spirit as La haine are American History X in the United States, and the Brazilian film City of God.

Author Bio: Sam Fraser is a literature-turned-film student at Université de Montréal. He still operates under the illusion that he might one day run into Denis Villeneuve or Xavier Dolan on the métro.