Following the downfall of fascist dictator Benito Mussolini, as well as their defeat in World War II, the Mediterranean power of Italy stood in a peculiar position by 1943. War-torn, humiliated, and unstable, Italian society and culture lay in disarray.

Art, and cinema in particular, was no exception – Mussolini’s Cinecitta studios had been heavily damaged during the war, leading to the loss of commercial Italian cinema’s focal point. Furthermore, the “Telefoni Bianchi” comedies, which dominated Italian filmmaking in the 1930s, came under heavy disparagement from several film critics, including Luchino Visconti and Cesare Zavattini.

Vying for more realistic depictions of society on film, this group of critics-turned-filmmakers saw to the end of the socially conservative and censored films of Mussolini’s reign to bring in a new wave of socio-political filmmaking that changed the face of world cinema indeterminately; Italian neorealism, from the war-stricken streets of working class Italy, was forged.

Despite the movement only lasting around 10 years, the influence of Italian neorealism is undoubtedly seminal. By using a unique range of stylistic noir techniques, as well as strongly emotional social themes, the neorealists stamped their name on cinema history in a way that no other film movement had done previously, or has done since. This, as well as 10 additional reasons explored in the list below, is why Italian neorealism is the most important film movement in the history of the medium.

1. Huge Levels of Influence in Contemporary Cinema

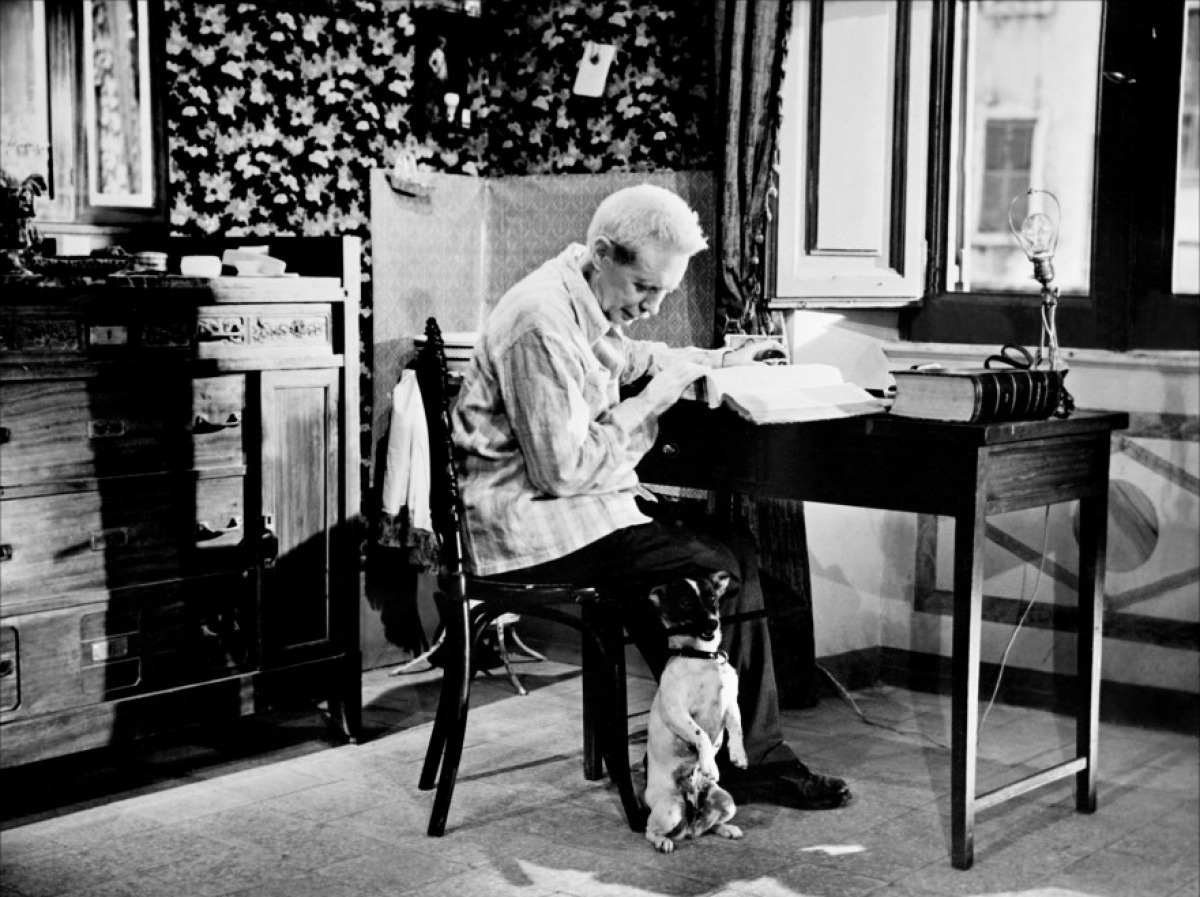

In spite of the neorealist movement effectively ending with Vittorio De Sica’s “Umberto D.” in 1952, both its thematic and stylistic approach to cinema can still clearly been seen in the modern and digital age. Specific examples include the Oscar-nominated “Nebraska” (2013), a film that draws from the social overtones of “Umberto D.”, particularly whilst also using monochromatic visuals to emphasise the grim reality of the picture – a staple of the neorealist visual arsenal.

The modern influence of neorealism, however, is embedded much deeper in the history of cinema as a whole, rather than simply being a referential style for cine-literate 21st century filmmakers. Its revelation of a new socio-political structure of filmmaking that used location-based sets and non-professional actors allowed an acceptance for new non-professionalism in cinema, which arguably can be seen in films such as “The Blair Witch Project” (1999), and all of the films in the “found footage” horror genre.

In addition, the cinema of Italy was revolutionised with neorealism, leading to one of the modern cinematic powerhouses; Pablo Sorrentino and Matteo Garrone are popular examples of the high quality cinematic legacy that Italian neorealism left behind. Even further than this, neorealism had vast influence on later film movements such as New Hollywood Cinema, the Polish Film School and, most importantly, La Nouvelle Vague, setting off a completely new period of cinema, and in turn everlastingly influencing the contemporary cinema we know today.

2. Popularised a Previously Unseen Socio-Documentary and Realist Style

Before neorealism, several film forms and genres existed from a range of different states. German Expressionism, Soviet montage and American film noir are generally the most acclaimed of the early cinematic world. However, none of these movements, despite their unique brilliance and innovation, had the brutal realistic edge of the neorealist style.

Typically using non-professional actors and filming on location (often the streets of Rome), the neorealist filmmakers produced an unprecedented film form that was akin to contemporary documentaries in its fairly simple camerawork and strong social themes. Furthermore, the working-class society of Italy is constantly portrayed in neorealism, becoming one its signature motifs that is arguably previously unseen in the world of cinema.

In abandoning the previous fantasist and escapist films of Hollywood, and the arthouse surrealism of Germany and Spain, neorealism presented to global cinema an altogether original approach to film, following the teachings of the ‘verismo’ literature movement of Italy in the late 19th century. Verismo in Italian literally means ‘true’, and authors such as Giovanni Verga and Luigi Capuana sought to represent the lowest of social classes with all aspects involved, even the most negative and pessimistic ones.

Neorealists – also with influences from parts of French poetic realism and the 1932 film “What Scoundrels Men Are!” (the first Italian film shot entirely on location) – were the initial group to convey this socio-documentary style in the medium of cinema, and from Luchino Visconti’s debut film “Ossessione” (1942) onwards, produced the first true realist and socially progressive movement in film history.

3. Paved the Way for La Nouvelle Vague and Several Other Film Movements

Often cited as the most influential film movement in Western cinematic history, even the prodigious impact of La Nouvelle Vague (the French New Wave of cinema in the 1960s) must have started somewhere. French New Wave auteurs such as Jean Luc-Godard, François Truffaut and Agnes Varda may have been radical filmmakers individually, but the La Nouvelle Vague movement on a whole owes a significant amount to the neorealist movement.

Like neorealism, La Nouvelle Vague emerged from young, confident yet disillusioned film critics of the respective state, who, despite their love of cinema, became cynical of commercial filmmaking, and decided to make their own ardent and artistically progressive features.

Shooting on location, monochromatic cinematography, and non-professionals, both in front of and behind the camera, can be seen constantly in the French New Wave – techniques learnt and developed from the original cinematic radicals, the Italian neorealists. Furthermore, the political and social facet of La Nouvelle Vague, one of its chief attributes, was certainly seen in the neorealist movement 10 years prior, which allowed for cinema to be seen as a more socially relevant art form, thus creating invaluable “cultural space” for the French New Wave to move into and become popularised.

As well as heavily influencing French cinema, both the film scenes of Poland and India were reformed after the wave of neorealism, with the famed Polish Film School and India’s Parallel Cinema movement (including the films of Satyajit Ray) following on thematically from their Italian predecessors. Neorealism was not just discerned by the West, but on a global scale – a symbol of its immeasurable and acute influence on world cinema.

4. Emphasised Absolute Humanism and an Appreciation of Humanity

Humanism – simply defined as the attachment of prime importance to the human race – can be seen throughout the neorealism movement. Despite this not being an unequivocal characteristic of every neorealist film, several directors, especially Vittorio De Sica, Roberto Rossellini and Luchino Visconti, examined Italian society through a humanist lens in their neorealist features, creating morally positive films that emphasised a respect and admiration for humans.

Notably, this was regardless of financial status and social class, often with the working classes being favoured in neorealism because they were the group most severely affected by the economic and social implications of the war.

This can be seen in De Sica’s seminal feature, “Bicycle Thieves” (1948), which follows Antonio (Lamberto Maggiorani) and his son, Bruno (Enzo Staiola), as they attempt to retrieve Antonio’s stolen bicycle, without which Antonio cannot commute to work, and therefore feed his family. In the final scenes, Antonio is saved by a bike owner (whose bike he attempted to steal) from being taken to the police station, in a moment of pure compassion and forgiveness.

The resulting ending – Antonio and Bruno in tears as they know their family is in deep trouble without a bike – is the most human and endearing from De Sica. Through a timelessly empathetic plotline that reflects real Italian society at the time, De Sica teaches his audience to treat those around you with kindness, providing the humanistic and altruistic values that configure the vast majority of Italian neorealist films.

5. Launched the Career of Several Acclaimed Filmmakers, Including Federico Fellini

Admittedly, many of the most successful neorealist filmmakers were closely attached to the movement itself, and when it effectively ended with De Sica’s “Umberto D.” in 1952, several of their careers suffered as a result. However, over this short 10-year period when Italian neorealism was dominant in Italian and European arthouse cinema, directors such as De Sica, Rossellini, Visconti Lattuada and De Santis created reputations that made them regarded (by fans and critics alike) as some of the most prestigious filmmaking talent of all time.

De Sica and Rossellini especially, who led at the forefront of the neorealist movement, were some of the finest directors of their era, with De Sica winning four Academy Awards in his lifetime (two during the neorealist years), and Rossellini winning the Grand Prize at Cannes for “Rome, Open City” in 1945.

Regardless of Rossellini’s awards and elite filmography, arguably his greatest contribution to cinema was his apprenticeship of a young Federico Fellini – one of the greatest filmmakers who ever lived. Before evolving into a directorial circus master, Fellini wrote for Rossellini – “Rome, Open City” was in fact penned by Fellini, who was nominated for an Academy Award for his work in 1947 – and learned from him, eventually directing his first film, “Variety Lights”, in 1951 alongside Lattuada.

By 1954, after securing his first successful feature with “I Vitelloni” (1953), Fellini moved on from the neorealist movement in its final hours, going on to create masterpieces such as “La Dolce Vita” and “8 ½”. Regardless of this, the launching of Fellini’s stupendous career must be credited to the neorealism movement, which, in addition to “Il Mago”, gifted us with numerous other eminent filmmakers, who are still recognised today as cinematic royalty.