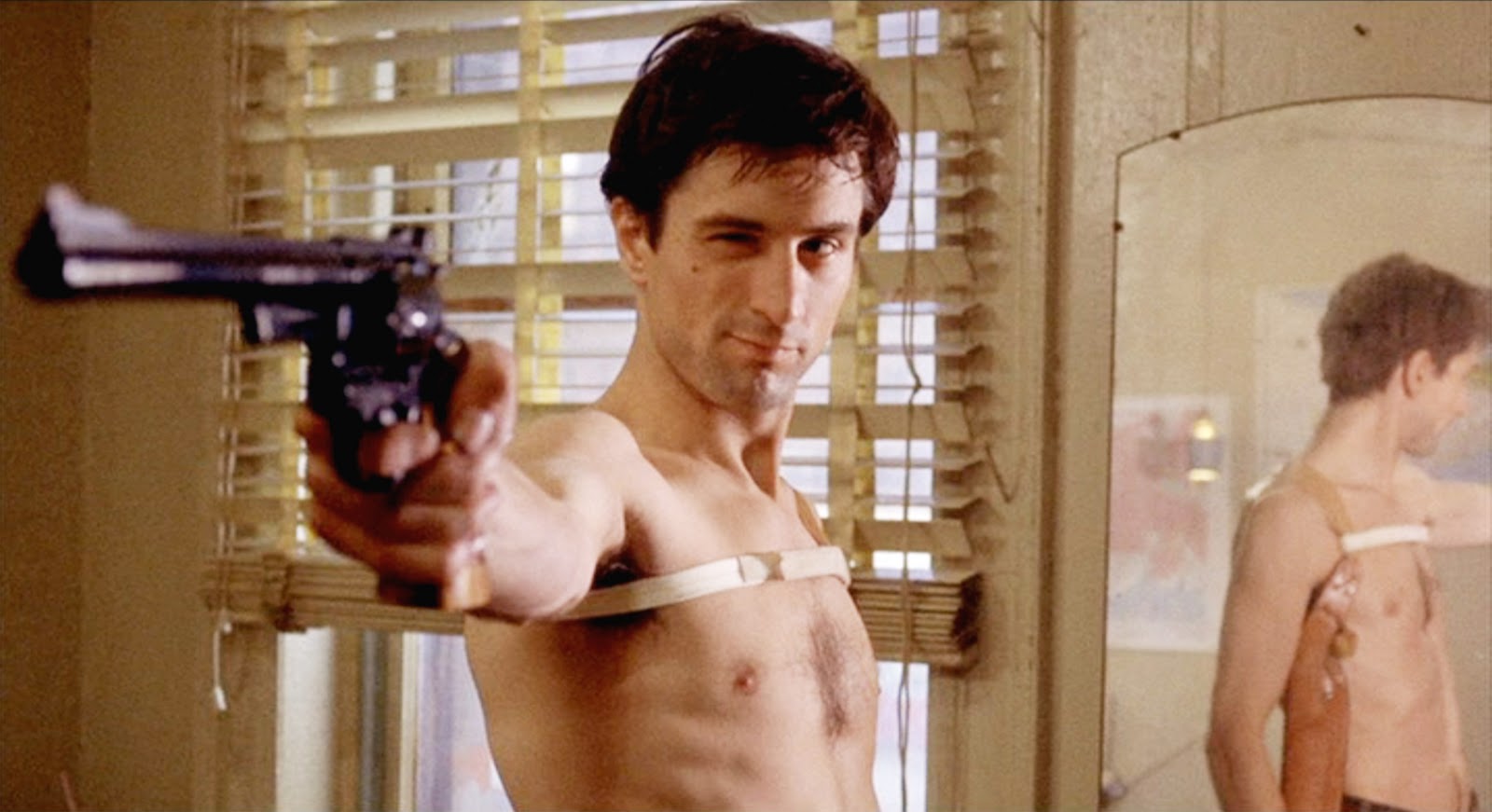

5. Taxi Driver

It is not all that surprising that a film that was a collaboration between the Catholic director Scorsese and Calvinist screenwriter Paul Schrader would have a religious bent. In this film, Scorsese presents us with “God’s lonely man” in Travis Bickle, a figure steeped in existential loneliness and befitting of the alienation of the modern man, making Travis into a distorted religious figure, a saint or a priest in this world that is out of balance.

Scorsese uses New York City in the 1970s, at its seedy apex, as a real-world wasteland in which the wandering figure of Travis must try to discover and preserve some form of good, piecing together the “fragments […] shored against my ruins” as Eliot writes of in his poem “The Waste Land.” Bickle is, or sees himself, as the only good person left in a world where God is seemingly absent.

This colors his interactions with Betsy (Cybill Shepherd) and Iris (Jodie Foster), as he sees them as something good in the morass that is the rest of the world. Schrader’s script to the film was famously influenced by both Bresson’s Pickpocket as well as Dostoyevsky’s Notes from the Underground, which makes its way into Scorsese’s direction.

Scorsese’s film is influenced by these works by existentialist artists whose work and existential philosophy was influenced by a religious sensibility, thus imbuing Taxi Driver with similar ideas and thematic concerns.

4. Mean Streets

A continuation of the ideas that Scorsese first explored in Who’s That Knocking At My Door? (Scorsese initially envisioned Mean Streets as a sequel to the film with Harvey Keitel’s Charlie being the same as the J.R. character he played in Knocking) but also an extension of them. While Knocking focused primarily on guilt in the sexual context, Mean Streets expands these Catholic ideas.

The film’s title and the quote by the famed hardboiled detective writer Raymond Chandler from which it is drawn (“Down these mean streets a man must go who is not himself mean, who is neither tarnished nor afraid”) hints at the central dilemma that Charlie faces as one who wants to be good and live in accordance with the Catholic Church while also being one who lives in the world of the streets amongst those who make their livings there.

This film, perhaps even more than Knocking, mirrors Scorsese’s own autobiography as he struggled to do and be good in his neighborhood while witnessing all the small crimes and sins going on around him in that world of the “streets.”

Charlie takes on the job of protecting his friend Johnny Boy (Robert DeNiro) and seeing it as a way atoning for his sins and performing a penitential act. It is fitting, then, that as Charlie has made Johnny Boy into this vehicle for penance, that Charlie ends the film kneeling and soaked in blood, all because of Johnny Boy’s own actions and transgressions.

3. Kundun

For the Catholic Scorsese, the 14th Dalai Lama might not seem like the most likely candidate to be the subject of a film. However, Scorsese is not solely interested in Catholicism and Catholic ideas, but rather seeks to engage with larger religious questions that go beyond depicting how people of a certain religious belief live.

It is in this tradition that Kundun participates as it depicts the life of the Tibetan Buddhist leader. What Scorsese gives us, in addition to a depiction of the life of this most holy and important of figures in Buddhism and world religion, is to depict what people see in these religious figures and what could lead them to belief.

Towards the end of the film, during his escape to India, the Dalai Lama says to one who asks if he is the Buddha, “I think that I am a reflection, like the moon on water. When you see me, and I try to be a good man, you see yourself.”

Scorsese is trying to make something akin to that reflection, to show what others see and believe in, both in this specific example as well as with religious faith in general.

2. Last Temptation of Christ

Last Temptation of Christ was a film that was the genesis of a great deal of controversy and elicited much negative criticism, particularly by religious figures. In particular, the focus of that ire was directed at a scene (in a “dream” or a hallucination) showing Jesus (played by William Dafoe) having sex with Barbara Hershey’s Mary Magdalene.

That scene, part of Satan’s final temptation of Jesus by offering him the prospect of a normal live rather than being the Messiah and the Son of God (which would include marriage and children and, thus, sex), was what those who opposed the film focused on, using that scene pulled completely out of context as justification for calling the film blasphemous.

However, what Scorsese did with this film was to create a work of cinema that engages with one of the most complicated aspects of Catholic theology, namely the idea that Jesus was both fully human and fully divine.

While depicting the Passion narrative, Scorsese shows Jesus’ humanity and his struggle with what he has been sent to do. But it is by depicting Jesus in this way that makes his final moments, crying out “It is accomplished!” before repeating it one more time quietly to himself before dying, that makes Jesus’ sacrifice all the more powerful, the redemption and salvation secured and punctuated by the tolling bells from Peter Gabriel’s soundtrack as the screen turns to white.

Rather than demeaning or blaspheming, what Scorsese does in this film (which, he clearly acknowledges in a title card, does deviate from the Gospel narratives and is not an adaptation of them) is to give even greater depth and complexity to Jesus’ narrative and in turn making his sacrifice (as well as God’s in sending his only son to pay the price for salvation) even greater as he secures redemption for mankind.

1. Silence

Scorsese’s more recent film, his long-gestating adaptation of Shusaku Endo’s novel (a work compared to a masterwork of British Catholic literature with Graham Greene’s The Power and the Glory), explores both a moment in the history of Catholicism in the world as well as larger questions having to do with faith, doubt, and the silence mentioned in the film’s title of God in the face of suffering.

Through this narrative of two 17th century Jesuit priests (Andrew Garfield and Adam Driver) traveling to Japan to try to find their Jesuit superior (Liam Neeson) amid rumors that he has renounced the faith amidst the public persecution of Christians occurring in Japan at that time, Scorsese gets to what lies at the heart of faith, but particularly the Catholic/Christian faith that is so familiar to him.

In many ways, Silence brings together many of the ideas that Scorsese has explored in his other religious films—suffering and its meaning, the existence of God, what it means to do good, the temptation of pride, and much beyond that.

The narraive of Garfield’s Father Rodrigues engages with what does it mean to be a believer, to be a Christian, and what one does or is willing to do because of that belief and how that might conflict with their own desires and preconceived notions.

It also speaks to the way in which Scorsese has engaged with these religious and philosophical questions in this film that it is compared to films by Ingmar Bergman, Carl Theodor Dreyer, and Robert Bresson, filmmakers whose work is known for its philosophical and theological concerns. That company is very appropriate company for Scorsese, particularly with Silence as these concerns that have manifested themselves across his cinematic oeuvre all come together in this film.

Author Bio: Thomas Bevilacqua is a doctoral candidate in English at Florida State University, currently writing a dissertation on mid-twentieth century American Catholic authors and auteurs. In addition to his interests in religion and its intersections with culture, he is also interested in mid-twentieth century American literature, culture, and aesthetics as well as the television show Mad Men. Follow him on Twitter @THBevilacqua.