Real life crimes have inspired some truly incredible films – Badlands, Bonnie and Clyde, Zodiac – but a number of respectable titles in this genre have slipped under the radar. Here are 10 overlooked True Crime pictures that set themselves apart:

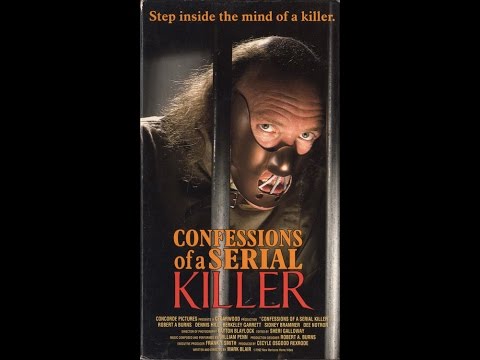

1. Confessions of a Serial Killer (1985)

A pivotal scene in Tobe Hooper’s The Texas Chainsaw Massacre involves a young girl being impaled on a meathook. What’s not commonly known is that Hooper originally wanted the hook to protrude from the victim’s chest, accompanied by a messy splash of blood.

Art director Robert A. Burns suggested to Hooper that implication is more disturbing and the effect should be 100% bloodless; this show of restraint helped ensure that Texas Chainsaw would remain a timeless classic, and Robert Burns is largely to thank.

After Texas Chainsaw, Burns dwindled in relative obscurity. He directed a forgotten psychological horror flick called Mongrel and worked as art director on several low budget genre efforts (Microwave Massacre among them), but would never again be involved with a project as widely known as Chainsaw.

In 1985, Burns played the lead role in Confessions of a Serial Killer, a film inspired by the life and crimes of murderous drifter Henry Lee Lucas. Shot on grainy 16mm film, the events are told in flashback as killer Daniel Ray Hawkins confesses his heinous misdeeds to a pair of police officers. It’s a flawed work, with flat direction and tacky music, but it flaunts a uniquely grim, scuzzy atmosphere that can’t be ignored.

Made one year prior to the (undeniably superior) Henry: Portrait of a Serial Killer; Confessions takes a similarly low-key approach to its subject matter, and contains several genuinely disturbing moments. While it isn’t a true, factual depiction of the Lucas case (that we’ve never gotten, and likely never will), it does stick closer to the facts than Henry.

The centerpiece of the film, the true reason to see it, is Robert A. Burns. Daniel Hawkins, as played by Burns, is quiet, deliberate, exudes a distant Southern menace. His emotionless voice and cold, droopy-eyed stare command your attention; it’s clear the man put a lot of thought and effort into his role.

Confessions of a Serial Killer is, sadly, difficult to find as it has never been properly restored or re-released in any fashion. Old VHS copies remain the only way to see this forgotten gem until someone, somewhere shows it the love it desperately deserves.

2. Dahmer (2002)

In the early 2000’s, generic serial killer biopics lined video store shelves. Dozens upon dozens of them (Gacy, Drifter, Karla, Night Stalker, Killer Pickton, B.T.K. Killer, Baseline Killer, Starkweather) were cranked out like so much processed cheese and most dwindled away into deserved obscurity.

Shot on a budget of $200,000, David Jacobson’s Dahmer is a film that soars high above its undistinguished contemporaries with a sensitive approach and fantastic performances, most notably from a young Jeremy Renner as the notorious Milwaukee murderer.

Jacobson’s film hops back and forth between eras, from Dahmer’s teenage years to Jeffrey as an adult, living in a shabby apartment that he’s turned into a veritable house of horrors. Renner handles himself astoundingly well; watching his controlled, expert turn here, it’s not surprising that he went on to Oscar nominations.

The film avoids being exploitative, functioning more as a small, smudged window into the life of its subject – it presents you with fragments from Jeffrey’s existence, pieces of what made him who he was, but never attempts to answer any of the questions it poses. Dahmer is one of the most thoughtful, intelligent serial killer pictures ever made.

3. Ted Bundy (2003)

Matthew Bright’s Ted Bundy isn’t about the man himself as much as his crimes, his fetishes, his insidious obsession. Bright, a tremendously gifted writer/director (Freeway, Forbidden Zone) with a subversive spirit and a fondness for dark comedy, made one of the riskiest serial killer biopics of all time with Bundy.

His picture chugs along excitedly with a sugar-rush intensity, a wicked smile on its face, giddy and relentless. Bright also (quite brazenly) injected an ample amount of morbid humor into the tale; legitimately funny moments sit alongside violent, disturbing ones and the shift is jarring, wholly unusual for this type of film.

Bright’s Bundy does a commendable job of touching on all the key points in the legendary case – two prison escapes, the flight to Florida, the prison romances – and flaunts a great lead performance from Michael Reilly Burke, more an exaggerated interpretation than an outright imitation.

The straight-to-video marketplace Bundy emerged into was a rather permissive one, and as such it’s a startlingly graphic film that doesn’t hold back. When the nasty bits occur, they’re genuinely repulsive; despite the presence of humor, and despite the films deliberately superficial surface, Bright never minimizes the awful things Ted Bundy did.

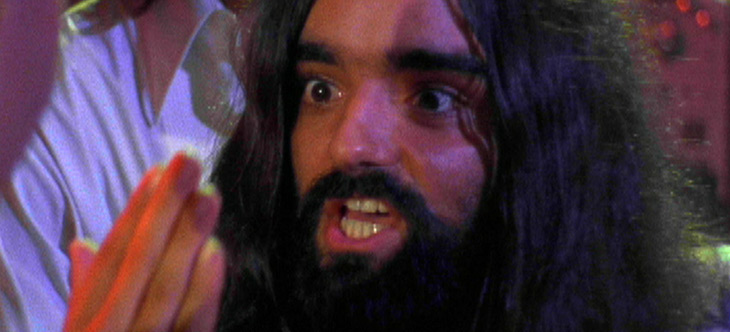

4. The Manson Family (2003)

Jim Van Bebber is an underground filmmaker based out of Ohio, active since the mid-80’s. Fiercely independent, his filmography is brief but impressive, with only two features amongst its titles: his debut, Deadbeat at Dawn, and The Manson Family, a triumph of vision and talent over budgetary constraints.

Van Bebber and co. began filming on Family in 1988 but the production was long and problematic, with shooting often taking place on weekends and the writer/director/co-star providing much of the financing himself.

His passion project was finally completed in 2003, 95 minutes long and comprised of footage shot over a period of fifteen years; this lengthy shooting schedule greatly aided the film, which traverses decades in telling the twisted tale of the Manson clan. Van Bebber’s scope is ambitious, combining traditional narrative storytelling, mockumentary-style news footage, and surreal hallucination montages (in addition, the film is bookended by scenes featuring a group of modern-day Manson wannabes terrorizing a news anchorman).

It’s a heady mix of elements, and while not all of these elements work (Marcelo Games is rather lackluster as Charlie), there’s an undeniable force that pulses beneath this movie, a kind of authenticity that can’t be faked or ignored.

Van Bebber has a deep love for exploitation cinema, the grindhouse aesthetic, and Manson Family feels at times like an old AIP flick with a larger amount of sex and gore, but it also possesses an earnestness that Jim Van Bebber backs up with undeniable skill and artistry. Even its flaws, in the end, are virtues.

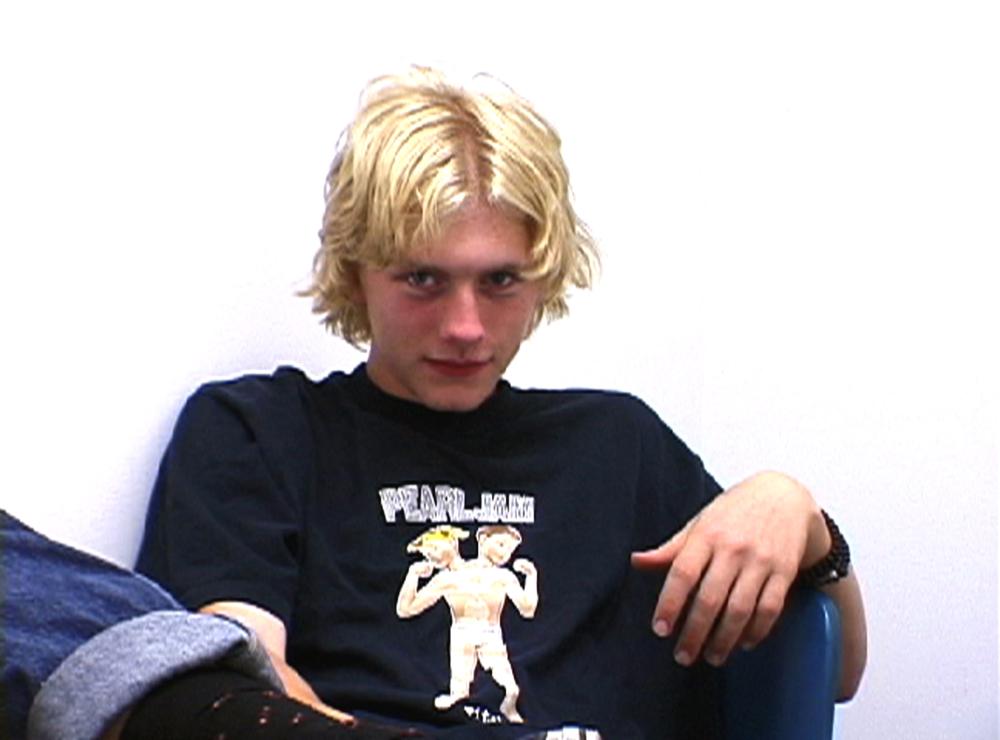

5. Zero Day (2003)

Inspired by the Columbine incident, Zero Day employs the found-footage technique to tell its story. A video diary of the days leading up to a school shooting (culminating in the shooting itself), it’s a suffocating experience: we watch as two intelligent, seemingly normal kids (far cries from the maladjusted goths the media presented to us) attend parties, relax at home with their parents, commit petty vandalism, and happily sort through the contents of their arsenal, excitedly stating that, “Zero day is coming”.

A sickly, creeping dread hangs across this picture, gradually growing more palpable as it becomes apparent that these young men are deadly serious and, furthermore, that this kind of madness is far more common than we’d like to believe. The incident itself, viewed through the lens of school security cameras, feels like twenty minutes spent in hell.

Zero Day was barely released at all (straight to DVD in America) and copies are hard to come by, but it’s well worth searching for. Writer/director Ben Coccio went on to co-author The Place Beyond the Pines with Derek Cianfrance.