When one takes up the study of film, either academically or as a hobby, it becomes important to see and study the films that make up the principal canons of the officially “great.” While it is enriching to view the lofty achievements of cinema history, one might well get burnt out on “greatness” if it becomes a single-minded pursuit. (This might account for the wave of books, articles and cults seeking out the worst of cinema in recent years, which is a somewhat funny but ultimately depressing quest, since achieving the worst isn’t a notable accomplishment.)

An equally fertile field of study is the seeking out of films with worthy elements which might not be total successes and/or ones that, for whatever reason, didn’t get a fair shake. While there is much to be learned from the sublime, there are important lessons lurking in the “nice try” category.

Where did the film succeed? Where did it go wrong? Why didn’t it connect with a broader public? (Though it may be acknowledged that great artistic achievements in any medium are often met with widespread public apathy and/or hatred.)

One striking fact is that many “nice try” films are also the works of those who created films termed “great.” The British author Somerset Maugham once stated that only a mediocre person is at his best at all times. In that spirit this list once more celebrates worthwhile also-rans.

1. Mr. Arkadin (1955)

As stated in a previous article in this series, Orson Welles is a cinematic god to some and every frame he ever shot (sez them) should be preserved in some lofty pantheon. To others, he was an increasingly windy old hack who once made a great film (1941’s immortal “Citizen Kane,” of course).

Virtually every Welles film has its partisans… and detractors. “Kane” sets at the far end of the spectrum with few serious detractors (though it does have some),while, at the other end, sits “Mr. Arkadin” (or “Confidential Report,” depending on the print one sees). This one has been much reviled but, even so, it did receive a few votes in the 2012 Sight & Sound greatest films poll.

The story may sound a bit familiar to not only the Welles faithful, but to any who know “Kane.” A petty criminal named Van Stratten (Robert Arden, a stage actor Welles went to great trouble to obtain for reasons known only to himself and who never had a major role in another film, for reasons easy to understand) is given an elliptical secret by a fatally wounded man on the docks of Marseilles.

The shadowy secret involves the mysterious multi-millionaire Gregory Arkadin (Welles, when the character makes a belated appearance). Van Stratten and cohort Millie (Patricia Medina, who met and married old Welles pal Joseph Cotten while making the film) proceed to the man’s castle estate in Spain, where Van Stratten intentionally strikes up a relationship with Arkadin’s daughter, Raina (Paola Mori, an attractive but none too talented non-professional who became the third and final Mrs. Welles shortly thereafter).

This flushes the none-too-happy Arkadin out but, instead of paying off or threatening Van Stratten, Arkadin makes him a business proposition. It seems the wealthy one has no memory of his life before 1927 and wants Van Stratten to track down the facts of that life (not unlike reporter Thompson in “Kane”). As the search starts yielding results (all criminal, to no great surprise), Van Stratten discovers that the old associates he uncovers are turning up dead and realizes that he will join them at the end of the quest!

The story is frankly as preposterous as it is derivative. The acting is uneven. Arden and Mori, as stated, are expendable. However, Welles (a bit over the top in his limited screen time), who had many friends in the acting community, managed to get several distinguished names for this small-budget film.

Van Stratten’s search leads to characters played by, among others, Sir Michael Redgrave, Mischa Auer, Peter Van Eyck, Gert Frobe, Katina Paxinou and Akim Tamiroff (the last two had previously worked together in 1943’s “For Whom the Bell Tolls,” which earned her an Oscar and him a nomination). They all give the film an uplift in their few screen moments.

Also, Welles, who couldn’t afford real sets at this stage of the game, had a superb eye for locales and the European sites on display here don’t disappoint, especially due to excellent black-and-white cinematography highlighted by Welles’ unique gift for composition.

This story went through many permutations (detailed in Jonathan Rosenbaum’s piece “The 13 Mr. Arkadins”) from it’s origin as an episode of Welles BBC radio series “The Lives of Harry Lime” and the finished film exists in a number of forms (and technically it was released in 1955 but sort of escaped out in many parts of the world over the next few years).

Perhaps the best version is the “complete” one The Criterion Collection commissioned in 2006, which contains all footage shot for the film and is edited according to Welles’ known wishes. However, as he was long dead by then, it can’t be considered definitive. That’s sort of apt for this film.

2. Death of a Cyclist (1955)

Every once in a long while, one stumbles across an excellent and unknown film from the past and is left to wonder why and how the film got lost in the shuffle. While European viewers, certainly of a certain age, may not put “Death of a Cyclist” in that category, in other places (including the US) this fact is true.

A major factor in this phenomenon is that the film is the work of Spanish director/writer Juan Antonio Bardem (yes, the uncle of present day Oscar-winning actor Javier Bardem). Bardem was openly a communist (which couldn’t have been easy in fascist-controlled Spain), though this film isn’t particularly political. He had a long career but most of his films are only known in countries of the former Soviet bloc (and several won prizes at the Moscow Film Festival, but they have yet to be unearthed for other parts of the world).

This did not endear him to US critics in the midst of the Cold War, and The New York Times’ Bosley Crowther (the critical prince of darkness for many classic film fans) saw to it that this film was DOA during its short US run. His reaction may have been more than political since the film plays much like a Michelangelo Antonioni film, though that director had yet to make a breakthrough at the time (and infamously, Crowther would also diss Antonioni’s great breakthrough, 1960’s “L’Avventura”).

The story has a simple premise: wealthy, married Maria (Italian actress Lucia Bose, dubbed for the occasion) is having an affair with university professor Juan (Alberto Closas). One night, returning from a tryst, Maria accidentally runs down a man on a bicycle.

The wounded man is still alive but needs immediate help, something the fearful Maria persuades Juan not to give for fear of discovery. The man dies and the pair are facing living with enormous guilt while maintaining their public façade. Though the film comes to a somewhat melodramatic ending, much of it is austere, subtle and cerebral. Hopefully, other good Bardem films may surface, but this one is a gem, even if that doesn’t happen.

3. Senso (1954)

Italy’s Luchiano Visconti is certainly neither forgotten nor overlooked. However, not all of his films are as well known or remembered as they should be. “Senso” is a great case in point. This film seemed to have more than its share of tough luck.

First of all, it marked the transition from the neo-realist films which had started Visconti’s career to the much more formal and operatic works of his more mature years. Though Visconti was famously a born aristocrat, he was also a devout communist. Many thought that his change to the later style, which often concerned privileged people living in lush circumstances, was something of a sell-out (really, more like blood telling). Next up was the casting.

“Senso” (loosely adapted from a famous Italian novel), is set against the backdrop of the war for Italian unification in 1866. A still-lovely and sensual countess, unhappily married to an older man, is sought out by a young and handsome, but opportunistic, young army officer. She knows that the man is only after her for material benefit but is too besotted and lovelorn to help herself from falling into his trap.

The original plan was to pair Ingrid Bergman with Marlon Brando (truly a match for the ages!). However, Miss Bergman’s then husband, the great Italian filmmaker Roberto Rossellini, wouldn’t allow her to work with anyone but himself.

Brando backed out at that point, saving Visconti from an embarrassing situation as the film’s backers thought their choice, American actor Farley Granger (pleasantly attractive and not incompetent, but far from Brando level), to be the better box office bet (he had recently done “Strangers on a Train” for Alfred Hitchcock). To match Granger, they hired Alida Valli, a star in Italy but a Hollywood washout in the late 1940s (though she did appear in 1949’s “The Third Man” at the end of that period).

Another problem to beset the film in the US was censorship. The film opened in the US in a much truncated version, badly retitled “The Wanton Countess.” It was also dubbed, never a good thing, though to everlasting astonishment, the English dialog was written by major literary figures Paul Bowles and Tennessee Williams.

Thankfully, history and restoration have removed many of the impediments. Also, one may now see that the actors are giving the performances of their careers. Also, the lush production values and Visconti’s skilled direction (he also directed opera and theater in Italy and it shows here) turn what could have been a trite and tawdry tale into a masterwork.

4. Army of Shadows (1969)

As stated in previous stanzas of this list, French filmmaker Jean-Pierre Melville looks so much better in retrospect than he ever did in life. His crime dramas are now international genre classics. It’s not so surprising that those weren’t better received by rather uppity critics and art house audiences at the time.

More surprising is the rather poor reception accorded to the few Melville films which touch upon his admirable time as a resistance fighter during World War II. His debut feature, the small budget but superbly made “La Silence de la Mer” from 1949, was somewhat swept under the international rug for decades. More distressing was the treatment accorded to what may well be his magnum opus, the masterful “Army of Shadows.”

Taken from a novel by Joseph Kessel (better known as the author of a book turned into a major hit and masterpiece the following year, Luis Bunuel’s “Belle de Jour”), “Army” concerns a group of ultra-dedicated resistance fighters. The men and women involved know that survival is a slim possibility but also know that living under the rule of their captors is no life either, and are prepared to make ultimate sacrifices, which all end up doing.

The film is full of escapes, executions, tortures, and all sorts of hardships, rendered in the kind of verisimilitude only someone who had been there could achieve. Melville is aided in no small part by a fine cast including Lino Ventura, Simone Signoret and Paul Meurisse.

So what happened to this film? Bad timing is the succinct answer. This film came out just after the infamous May riots took place, which rocked French society in 1968. The action of the film honors the then General DeGaulle. However, in the then-present day, he was France’s president and, by that time, quite unpopular with the younger generations in France.

Also, much like the youth in the US, French youth, looking askance at the then-recent Algerian conflict, were no longer thinking of the resistance period as heroic. Poor domestic reviews killed any international chance. Melville, who sadly would die abruptly a few years later, went back to his traditional crime thrillers for his final two films (however, the films, 1970’s “Le Cercle Rouge” and 1972’s “Un Flic,” were among his best). The film was finally exported in 2009 and promptly was hailed as one of the best of the year and won more than one award. Oh well, better late….

5. Dillinger is Dead (1969)

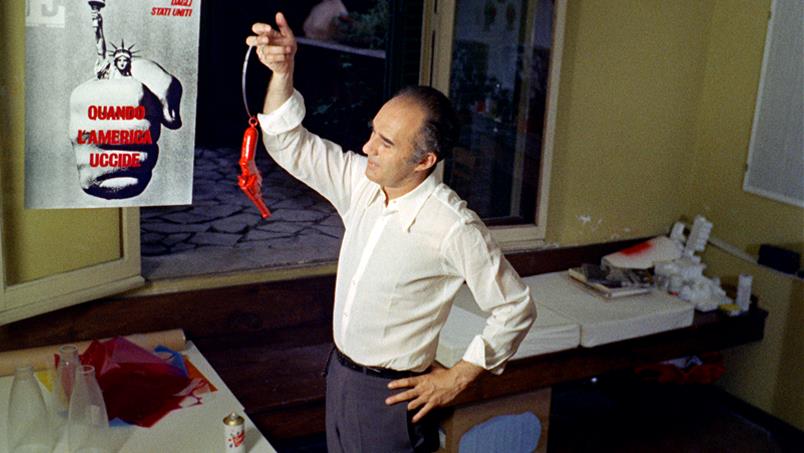

Black comedy can be a dicey genre. If the film isn’t too smug and pleased with itself for its outrageousness, it could ride a fine line of provoking outrage and/or being taken too seriously. Italy’s Marco Ferreri can surely testify to this better than most, since he spent his entire career in this sub-genre. While he has had his successes (more domestic than international), one film looks more and more to stand above his canon. That would be the oddly named “Dillinger is Dead.”

First off, this film really has nothing to do with the infamous US gangster of the 1930s. The title comes from a headline in a vintage newspaper used to wrap a gun, which very much has to do with the plot. That plot centers on Glauco (noted comic actor Michel Piccoli), a successful but unsatisfied maker of gas masks. He comes home to find his wife (60’s icon Anita Pallenberg) in bed with a migraine, and having left him a cold and unsatisfying dinner. While making himself a much better meal, he stumbles on said gun in said newspaper (referencing a man who surely never suffered such indignities).

From that point on, things which may or may not be real start filling the screen. Maybe Glauco seduces the maid (French star Annie Girardot). Maybe he doesn’t kill himself with the gun more than once. Maybe quite possibly he ends up using the gun in a far different manner than suicide around dawn and then proceeds to a fantastic sort of experience as a finale.

This is a funny and sharp film. It may well come across as misogynistic, but a black comedy must offend someone, right? Well, the lot of black comedy is not to please everyone. Give this one a chance and it may well please, though.