Some films are remembered, some forgotten. Some are praised and some are not. The odd thing is that initial reactions may well not count in the long run concerning a film’s ultimate reputation.

There are also degrees of fame, rejection, praise and damnation. A well-made film may be little known and seen but loved by the few who did find it (a cult classic, if one wishes, such as 1955’s “The Night of the Hunter” or 1949’s “Gun Crazy”). There are well known films which have garnered very little love (1963’s “Cleopatra” or 1973’s “Mame” can serve as examples). And then there are some which drown in lukewarm water eternally, both critically and with the public, but which may well have things to recommend them.

Maybe they aren’t the ones always buzzed over, but they shouldn’t be completely overlooked either. The following list contains films that don’t get talked or written about often enough, but which don’t deserve neglect. Some are better known than others, but all could use a good shoutout.

1. Yoyo (1965)

The fact that “Yoyo” is not better known really isn’t surprising. It shares the same basic fate as the other small handful of films created by its star/director/writer and that’s too bad (though it and the other films may have their chance at some point).

Who loves the comedy of the great silent clowns more than the French? Yes, many claim to, but the French put their money where their mouth was by continuing the silent tradition long after the silent era was over (only the late Jerry Lewis, infamously loved by the French, managed that trick in Hollywood) . Many know of the famed and praised (though not prolific, either) work of Jacques Tati in from the late 1940s through the early 1970s.

However, there was another silent clown (probably a disciple of both Tati and the silent masters) who practiced the art of silent comedy along with Tati in the 1960s and 70s and little bit longer. His name is Pierre Etaix. Though he had a long career as an actor, he had but a short one as a filmmaker and left behind only a handful of films. Why? His work was wonderful but there was something delicate and precious about his films and himself as an artist.

Perhaps the handful of films he left (after a long and happy life), all such gems, were the best that could be expected. He won an Oscar right off the bat for the 1962 short “Happy Anniversary” and, that same year, released his first feature, the delightful “The Suitor.” However, his crown jewel came three years later.

Shot in black and white (just making it in while such a thing was still possible in commercial cinema) and largely silent, “Yoyo” is like a mixture of Chaplin, Fellini and (yes) Jerry Lewis, but all of it is Pierre Etaix in the end.

As an actor, he plays two roles. Opening in 1925, his first character is an unhappy millionaire, feeling alone in his palace-like mansion, despite all the best company money can buy. His only happiness is the memory of Elle (Claudine Auger), a circus performer and only woman he ever loved (and lost).

When the circus plays a return engagement in town, the man recognizes, without being told, that Elle’s son, Yoyo, is also his. He takes the pair into his home and his chief desire is to train Yoyo (Etaix also when the character become an adult) to be the world’s greatest clown. Yoyo wants this but he also wants to restore the beauty of his father’s mansion, which falls into disrepair when the family fortune is lost in the Great Depression. However, modern times (including TV) are present in even the fantasy world of this film, and a simple clown may find it hard to make so much money.

Etaix, like so many other artists (some comedic), had hard luck with business partners. Though European critics of the day loved his work, the films fell into a legal morass which kept them tied up and out of circulation for decades, allowing a few generations of film fans to grow up knowing nothing of Etaix and his work. Well, thankfully, that is a memory now with restoration and redistribution. The films still have a lot of catching up to do, but there is no time like the present to start!

2. Kwaidan (1965)

Sometimes a prophet (or artist, as the case may be) is truly without honor in his own homeland. Or, if one will, a film only may have its true worth judged on foreign soil. A great case for this is the history of the epic supernatural film “Kwaidan.”

Horror fans in the US and Britain may find it odd that this film could be considered overlooked. It has long been a staple of horror cultist (a smallish but quite loyal and appreciative group). It was also an Oscar nominee for Best Foreign Language Film and is a selection of the Criterion Collection. However, it was a big and infamous flop in its native Japan upon release.

“Kwaidan” (which translates out to “spooky/ghost story”) is a four part omnibus of stories set in feudal Japan. All are laced with supernatural elements. The film features a handsome production design in stunning and colorful widescreen. However, there were some mitigating circumstances concerning its dramatic trust. The source of the stories was not a Japanese writer but European author Lafcadio Hearn (which might have been a major irritant in the Japan of the day).

The director, Masaki Kobayashi, had created the massive, stunning (too little seen) “The Human Condition” (1959-1961), but wasn’t known for genre films such as horror films. That was also another point. Though there are horrific elements in this film, scary isn’t a ready adjective for it. The real horrors in these stories are loss, regret, dishonor, and the burden of the past (especially guilt).

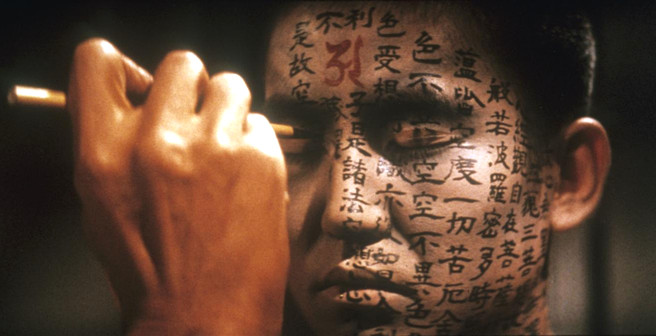

The first story sees a samurai returning to the woman whom he deserted for his career, finding her seemingly the same, but coming to a terrible discovery. The second finds a woodcutter carelessly breaking a bargain made long ago with a supernatural spirit who helped in in a cataclysmic snow storm, and is and paying the price. The third (cut from exported prints for several years) finds a blind singer/musician imperiled by vengeful ghosts who want his life force, something loving and helpful monks try and fail to help him with in a meaningful way. The last finds a man haunted by an image he sees every time he looks into a cup of tea.

Perhaps this was too cerebral and basic in storytelling concepts for domestic audiences. However, it looks most interesting, if not quite completely satisfying to some, in other markets. “Kwaidan” may not be a crowd pleaser and certainly not the gloriously trashy genre wallow a description may promise, but it is a film of merit from a country where the supernatural genre is taken quite seriously.

3. One Eyed Jacks (1961)

Marlon Brando was truly one of the seminal acting forces of the 20th century. He didn’t just leave his mark – he changed his profession in some pretty permanent ways. However, examination of his film career shows that he had five incendiary years at the start (mostly with his work with then-mentor, stage/screen directing great Elia Kazan) and then… well, calling his record up and down might be charitable.

After making 1957’s “Sayonara,” he did not have anything resembling a hit until his legendary comeback in the 1972 classic “The Godfather.” What filled the years in between? There were nine commercial (and to a large degree critical) flops, some more deserving of that ignominy than others (though he was almost always interesting, if nothing else, and often quite good in sometimes trying circumstances).

Perhaps the most compelling film he made during this period was also his only foray into directing (and this film’s infamous and troubled shoot guaranteed that it would retain that distinction). The film was a western taken from an obscure novel by Charles Neider entitled “The Authentic Death of Hendry Jones.” Brando always intended to produce (this was before it was realized that his bad streak was more than just a short term thing), but he found that he was dissatisfied with the studio-appointed writer and director (some juvenile hacks named Calder Willingham and Stanley Kubrick!). Just as with his acting, Brando was going to do it his way… which he did for better and worse.

The plot is not unusual, though the treatment is off-beat. In the Old West, criminal Rio (Brando) is part of the gang overseen by “Dad” Longworth (Brando pal and Oscar winner Karl Malden, giving a fine performance). A robbery goes very wrong and Dad leaves Rio to twist in the wind… in a Mexican jail, until he escapes five years later. Rio’s intent is to exact revenge on Dad. He tracks the man down to a small town on the southern coast of California (and the seaside setting is striking for a western).

Dad has reinvented himself as the town marshal (!) and is married to a lovely Mexican woman (veteran character actress Katy Jurado) and the stepfather to her even lovelier young daughter, Louisa (the beautiful and ill-fated Pina Pellicer). Though Rio feigns friendship, he and Dad aren’t fooling one another, and the fact that the Rio and Louisa fall in love doesn’t lessen the fury they eventually unleash on each other at all.

Brando directed this film very much like he acted in it. It goes at its own pace, completely mindless of time (the rough cut was infamously four hours plus, whittled down to half that length and still far from speedy). The film is full of quirks and such usual Brando preoccupations as mutilation. However, it is also a most individualistic picture. No one else could or would have made it this way. Like its maker, it may be a pain in some ways, but one worth putting up with.

4. The Adventures of Robinson Crusoe (1954)

Anyone studying film history today would be amazed that there was a time when the cinema’s greatest surrealist, Spain’s Luis Bunuel, was overlooked. However, being banned (for life!) from filmmaking by the Catholic Church might well do that to one’s career. Bunuel’s early films, especially 1930’s “L’Age D’or,” offended church sensibilities (which provided much fodder for the filmmaker once he finally got back to the mainstream).

Due to this, he spent a long time in purgatory, which took the form of Mexico, the country to which he fled. He lived there, working in the publicity department of Warner Brothers’ Mexican office, long before he was finally to able to direct a film even in that remote place. Some of his Mexican work is mundane (just work for hire, but he had to restart somewhere), but some of it is as good as any he ever did. Coming somewhere in-between but leaning definitely to the good side is Bunuel’s only English language film, “The Adventures of Robinson Crusoe.”

Now, the reader may be forgiven for thinking that this one sounds like something only a kid with a book report due the next day might want to see. Of course, this is a cinematic version of author Daniel Defoe’s classic novel concerning a merchant adventurer who gets shipwrecked alone on a desert island for many years until finding some companionship in another castaway, a native he dubs “Friday.”

It sounds like a children’s adventure story, but it’s not (and a close reading of the book would confirm that). Bunuel plays the first two-thirds of the film as an incisive study of the effects of isolation and the difficulty of survival. After Friday appears late the in film, the story shifts to a wry study of power relationships, with Crusoe’s first reaction to finding a companion after so many years is enslaving Friday with chains!

One key element that’s mostly missing from the film (and is a cause for disappointment to some) is Bunuel’s famed surrealism, save for one dream sequence. One great element the film possesses is a powerhouse performance from Irish stage and screen actor Dan O’Herlihy, which garnered him an Oscar nomination (then unheard of for a miniscule budget, non-Hollywood film, and reportedly he came close to beating out Marlon Brando in “On the Waterfront” for the award).

Due to being what might be dubbed an “orphaned” film (with no studio or large company owning and keeping track of it for decades), the picture all but vanished into the ether for good. Happily, it was rescued (apparently in the nick of time) and is getting back into circulation again. It may never be in quite the same category as 1967’s “Belle de Jour” or 1970’s “Tristana,” but “The Adventures of Robinson Crusoe” is not a film to be dismissed, either.

5. Le Deuxième Souffle (1966)

France’s Jean-Pierre Melville came very close to being overlooked period. A short-ish lifespan and only 14 films, mostly genre efforts, didn’t put him at the art house forefront during his lifetime (and two films which weren’t genre efforts, 1949’s “Le Silence de la Mer” and 1969’s “Army of Shadows,” didn’t have wide showings abroad until long after Melville’s death and his career starter, 1950 Les Enfants Terribles, is forever the property of its author-producer, Jean Cocteau).

Melville, a notable fighter in the Resistance, knew of honor, valor and a code of ethics in even the most unlikely places and circumstances. He imbued his many films concerning crime and criminals with these qualities. The figures in a Melville film might be low and undesirable by the precepts of the larger society, but they have their own principles and guidelines and, quite often, they are tragic on their own terms.

Some of the best of Melville’s films in the crime genre are “Bob le Flambeur” (1956), “Le Samouraï” (1967) and “Le Cercle Rouge” (1970). Many of his later films made use of international stars such as Alain Delon (never better than under Melville’s direction) and Yves Montand. Though another film has been gaining traction in recent years, “Le Deuxième Souffle,” which stars Lino Ventura and Paul Meurisse, two respected European actors without great international reputations, has been somewhat overlooked.

The plot follows a small band of three criminals as they escape from a maximum security prison. The leader (Ventura) knows it’s best for him to leave the country as quickly as possible. However, for a variety of reasons (more honor among thieves), he feels compelled to pull off one more big heist before leaving, especially after getting involved in a gangland killing. Complicating this is a dogged police inspector (Meurisse) who has long been the man’s nemesis and is equally determined to bring him back… dead or alive.

Maybe the plot isn’t the most original (genre plots rarely are) but, as ever, it’s how it’s handled that counts. Melville always treated his plots as if they were Hamlet-level pieces and always gave them the finest treatment his adroit ability could conjure. Perhaps this film came in the middle of too many similar ones from the filmmaker. Perhaps more star wattage might have helped. However, taken just as a piece of filmmaking, divorced from anything surrounding it, this is a fine effort and worthy of the later-day praise awarded to Melville.