Poland was one of the first Eastern European countries to enjoy the new invention of cinema-and that happened before it was even officially a country. Though it was at the time divided between Russia, Austria, and Germany, Polish cultural live was thriving on national identity as a form of hidden resistance. Soon after first Polish films were made, Poland reemerged on the map as an independent country. Adaptations of literary classics were very popular, as were cheap melodramas.

An interesting sub-market was the Yiddish cinema, which was based on a rich Polish-Jewish literary tradition and produced some unique works. And then World War II happened, an event that forever altered Polish history and continues to be a part of national psyche. The Jewish population was destroyed in the Holocaust, and many millions of Poles lost their lives, either during a brutal Nazi occupation, equally rough Soviet liberation, or an ensuing civil war.

It must be noted that Polish artistic and literary tradition was conflict-based to begin with, and the horrors of war only served to deepen the examination of human condition and the search for the meaning of existence. Soon after the war, Andrzej Wajda helped establish Polish cinema as artistic force, and throughout 50’s and 60’s, he and other talented writers and directors were able to create cinema that took the best of both worlds, Western and Socialist.

The initial failure of Solidarity movement led to the officials tightening the screws, but once the chains of Communism were lost, Polish cinema was able to emerge reinvigorated, with growth of more recent talents like Kieslowski or the return of the exiled dissidents. To this day, the artistic high mark is maintained in Poland, particulalry when it comes to making works of cinema that are striking in visual form, a specialty of Polish art since the days of Mickiewicz and Matejko.

1. The Dybbuk (1937). Dir. by Michal Waszynski

The opening film of this list was justly celebrated at the time, but, though made in Poland, is not technically Polish. It is a film from a vanquished culture-a Yiddish film. Based on the famous (at the time) play by Ansky, it’s a haunting and very atmospheric “Hasidic Goth” masterpiece of love and betrayal, possession and exorcism. Not since the heyday of German Expressionism was the mystical power of the spirit so imaginatively transferred onto a reel.

The tale of a young man and a young woman, betrothed to each other before birth by their respective fathers and unhappily reunited later in life (the young man, to claim what’s his, dies and becomes Dybbuk of title, the wandering spirit) is set in a rich milieu of a provincial shtetl, full of traditions and beliefs.

The world of the rural Polish Jews is presented in all detail, both the day-to-day life and the all-important religious ceremonies. It is a world that would soon be annihilated by the different horror, that of Holocaust. This film is an invaluable memento and a time capsule of that world.

2. The Ghosts (1938). Dir. by Eugeniusz Cekalski and Karol Szolowski

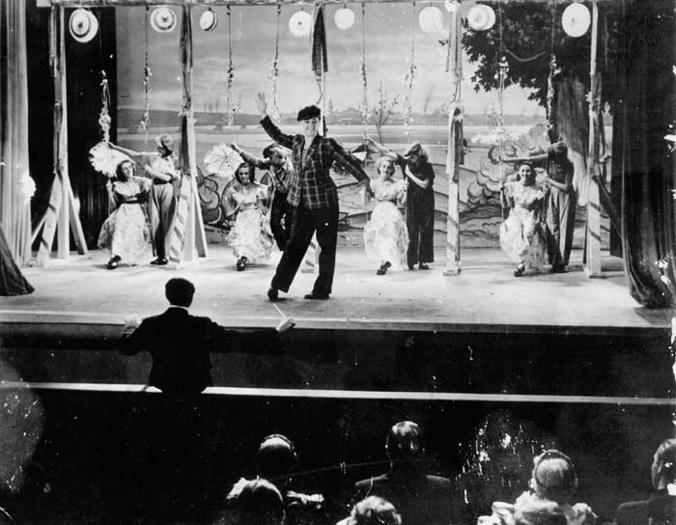

A film about the stage that at no time looks or feels stagey. Welcome to the shiny and seedy world of cabaret. While the story is fairly conventional and designed to titillate the middle class moviegoers with the “forbidden fruit” (it focuses on the misadventures of two cabaret chorus girls and features backstage bickering, seductions, abortions, and oodles of melodrama), the style is mesmerizing and brims with invention.

All the cinematic tricks of the time are used: striking angles, creative use of sound, atmospheric lighting, vignette structure. Many scenes stay with the viewer: the dancing shadows of the opening reel, tracking shot of the moving railway car (with the thoughts of passengers in a voice-over), lyrical footage of raindrops on water, and the best use of parallel montage East of Griffith.

Cekalski here again shows himself to be an explorer of the film form, continuing the experiments he undertook in the influential 1937 short Three Chopin Etudes (which he remade in the USA in 1944). Rivals the best works of Lubitsch and Max Ophuls in the genre.

3. The Last Stage (1948). Dir. by Wanda Jakubowska

Many haunting films about the concentration camps of World War II have been made. But, perhaps, none are this personal. That’s due to the fact that both the Polish director of this film and her German co-writer were at one point inmates at Auschwitz. The tragic events depicted here were powerfully striking at the time due to the immediacy of the events, and this film has influenced almost every concentration camp film since, including (by Spielberg’s own admission), The Schindler’s list.

Jakubowska employs almost no cinematic tricks, instead letting the truth speak for itself. This isn’t the lacquered Social Realism, neither is it the naturalism or the Italian Neo-Realism. This is ultra-realism, an unflinching presentation of one of the most heinous crimes that humans committed against other humans. A landmark in the cinema of a country that suffered tremendously in the war, and a step towards healing.

4. Wajda’s War Trilogy: A Generation (1954), Kanal (1956), Ashes and Diamonds (1958)

Andrzej Wajda will feature prominently on this list, and deservingly so-for over 60 years he has been the creative soul of Polish cinema, and, perhaps, the filmmaker that best captured his people’s sensibility on film. This informal trilogy established not just him but entire Polish cinema as a force to be reckoned with, while still remaining nothing short of amazing to look at.

A Generation (1954)

Wajda’s live-action feature debut already hints at the immense talent that is emerging, traditional as it is. The story of a group of youths from an impoverished neighborhood who form a sincere but mostly inept resistance unit in 1943 is nothing to write home about in terms of plot, even though it features good acting turns (look for a teenage Roman Polanski in one of his first film roles). But already Wajda excels in technique.

The world is put on notice from the very opening sequence, where for over two minutes the camera pans and tracks along a desolate slum landscape, finally zeroing in on aimless young men playing a knife game. The rest of the sequences similarly brim with life and nerve, particularly where one of the young men is chased by the Gestapo to the top of the flight of stairs. For the first but definitely not the last time Wajda greatly enhances his story with amazing technical elements.

Kanal (1956)

Out of darkness, a masterpiece. Wajda’s progress from A Generation is astounding. This is a war story that goes from bad to worse to hell. During a Warsaw uprising of 1944, a remnant group from the routed Resistance unit attempts to escape capture and death through the sewers. Sherman famously said “War is hell”. Had he seen this film, he would have said war is shit. One by one the fighters succumb to wounds, exhaustion, poisonous gas, and overall weariness.

Seldom has the downward spiral been so mercilessly brought to screen. And yet the visual style is simply exhilirating. The play of shadows is fantastic, and the sound mixing belongs in the all-time top 5, with fragments of image or sound coming at the spectator at jarring and irregular intervals. Easily matches the best Hitchcock thrillers and examples of German Expressionism in style while posessing intense amount of substance.

Ashes and Diamonds (1958)

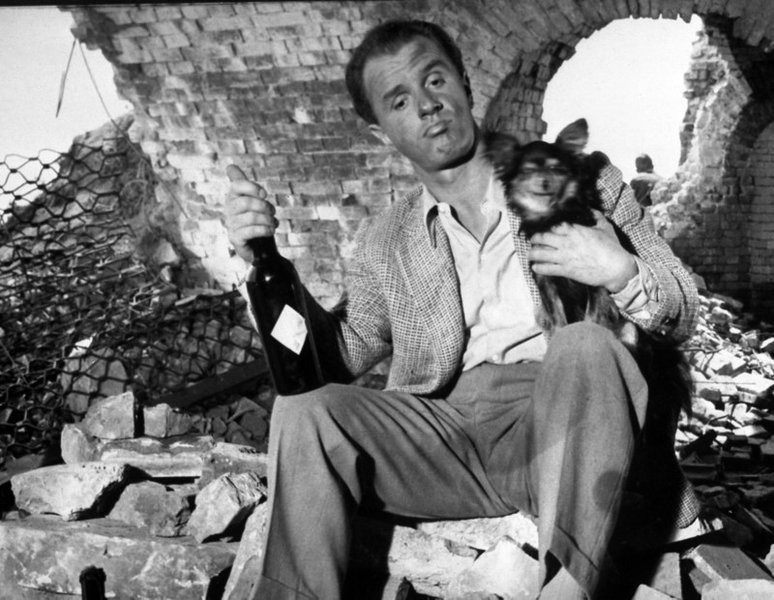

Arguably, the greatest Polish film ever made. Here style and substance achieve a perfect marriage. The war is officially over, and the Nazi occupation is replaced with Soviet “liberation”. But a civil war rages on. The pro-Western Armia Krajowa (Home Army) battles against the Soviet-backed Armia Ludowa (People’s Army). Who’s right, who’s wrong, and does it really matter?

Besides the phenomenal visual look of the film, it’s elevated to masterpiece status by a dynamite performance of Zbigniew Cybulski as Maciek, an AK fighter on the mission to assasinate a Soviet-backed politician. World-and-war-weary, always wearing black jeans and shades, Maciek is as engaging as any hero or antihero played by Marlon Brando or James Dean at around the same time. He is forced to choose between duty and desire for rest and normal life.

A Generation opens with a stunning sequence, while Ashes and Diamonds ends with one, as a wounded hero collapses at a city dump, his blood on a white blanket forming a replica of the Polish flag. Together with other striking sequences, the film is an unforgettable experience.

5. Eroica (1958). Dir. by Andrzej Munk

Along with Wajda, Munk was a rising talent of the 1950’s Polish cinema, a period after Stalin’s death when artists were finally able to explore their nation’s history. This is his masterwork, a two-part satire on the concept of heroism, long esteemed by the Polish romantic tradition. The first part focuses on the Warsaw resident, a cowardly cheater and drunk, who unwittingly joins the uprising and becomes a reluctant hero.

Shot at times like a slapstick comedy set at the war zone, it has many hilarious scenes (a drunk. vs a tank is the most memorable). The second part takes place in an officers POW camp at the end of the war, and is far grimmer. At that camp, a hero and a legend is an office who, years ago, allegedly made a successful escape. Except, he didn’t, and is hiding nearby, sporadically fed by a few of his friends in on the secret. Her, Munk’s unique style is more present too-particularly, the gradation of shots and the inventive use of close-ups.

A third part was made as well, a retelling of a romantic Polish legend, about the wartime couriers in the mountains, but was released separately in 1972. Munk has succeeded in creating a film that is original in style and unconventional in content.

6. Dom (1958). Dir. by Jan Lenica and Walerian Borowczyk

A highly stylistic and influential animated short, made by two of the premier Polish graphic designers/filmmakers. Live action is combined with various animated techniques (cut-out, photo montage, pixilation, stop-motion) to take us into an apartment and a mind of the female protagonist.

What follows is a loosely associative presentation of her thoughts, including a repeated visit by a mysterious, Magritte-inspired silhouette, an Eadweard Muybridge-like footage of two men boxing and fencing, a mess of blonde hair coming to life and wreaking havoc, and her making out with a living mannequin head, among other things.

A precursor of larger things to come from both Lenica and Borowczyk, and an acknowledged influence on such innovative animators as Jan Svankmajer, George Dunning, Yuri Norshteyn, and the Quay brothers.

7. The Last Day of Summer (1958). Dir. by Tadeusz Konwicki

This film makes Jarmusch’s Stranger Than Paradise and Lynch’s Eraserhead seem like an overblown MGM epics in comparison. One of the most minimalist films ever made, it makes do with a natural setting, an Arriflex camera, six thousand meters of bw film, a crew of 5, and a cast of 2.

That’s all Konwicki need to present a compelling, Golden Lion (Venice) winning story, which on the surface is simplicity itself-on a last day at a Baltic resort, a woman meets a man among the sand dunes, who professes his love for her. It takes a while for these damaged souls to merge, but the merger creates more questions than answers. Their solitude is only occasionally interrupted by fighter jets flying overhead, the only signs of outside world. Besides them, there is only a desolate beach, little pieces of amber, sand, and the wind.

A renowned writer prior to turning to filmmaking, Konwicki tells his haunting tale without resorting to cinematic tricks-and yet manages to cover multiple layers. The story is at once straightforward (what you see is what you get) and highly symbolic (the echo of the devastating war rings loudly), managing to cover past, present, and future. All in about an hour of running time. The background music played as a whistle deserves special mention-perfectly fits both the realism and otherworldliness of this amazing film.

8. Night Train (1959). Dir. by Jerzy Kawalerowicz

A subtly stunning visual poem on the rails. Here, the train is presented as a mobile microcosm of society-populated by unhappy couples, flirtatious wives, religious old women, concentration camp survivors, runaway murderers, libidinous Lotharios, police, etc. Set against this rich background is a subtle game of emotions played by several characters.

Overall, Kawalerowicz presents a fascinating study of life in transitions. The rapid beginning, when we expect a chaser, gives way to a psychological drama, although the detective part of the story resurfaces with vengeance towards the end (allowing the director to explore the society at large). Aesthetically, it offers ample rewards. Many unforgettable images-the extreme close-ups of wide-open eyes, droplets of water on foreheads.

The lyrical jazzy score (until the “killer scenes”) adds to the atmosphere. Kawalerowicz largely keeps his camera static, achieving the necessary dynamism with virtuoso editing. He would go on to make films much larger in scope, but this one remains his early masterwork.