When all is said and done, plot are wrapped up and character arcs are drawn to a close, it’s up to the final shot of the movie to answer any remaining questions, raise more questions or simply leave you with a sensational final image from which to depart.

The final shot of a film can alter your entire perception or image of the feature you have just witnessed, through the variations in composition, tone and style can change the effect a movie had on you and within its final shot rests the entire summary.

Will you leave the movie, hopeful, confused, inspired or haunted? There are limitless possibilities for how to manipulate your audience with the ending of a movie, right up until the final frame.

Just to clarify, I’m talking about the very last shot itself, not the entirety of the ending. I have to say that because shots like The Graduate’s fading smile or Norman Bates and his superimposed mother will not be appearing here. I know it seems like knit-picking but what’s a list without consistency? Also, spoilers ahead, you have been warned.

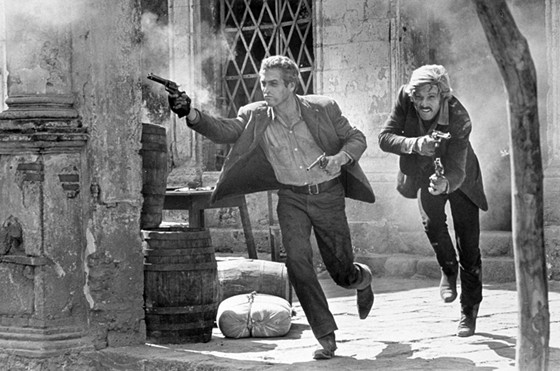

20. Butch Cassidy and the Sundance Kid

Here is a classic example of how a simple freeze frame can leave a haunting impact. Even before the first frame of the 1969 western, we know the eventual fate of our two protagonists (unless you can’t recall historical events), but over the course of the film we become attached to the two weary outlaws in search of a more profitable career.

But with the law finally catching up with the duo in Bolivia, they are surrounded and facing certain doom, the only thing left to do is make a final charge and go out in a blaze of glory.

But of course, we don’t actually see Butch and Sundance go down, with director George Roy Hill freezing the shot moments before the two are gunned down, leaving it a single freeze frame that haunts us forever. Why? Maybe it’s because it captures the last fleeting glimpse of life and hope, the faintest possibility of escape instead of a violent and bloody end.

Of course we still don’t see their demise, but in a way the sounds of endless gunshots followed by a still silence are even more disturbing. We have followed these two men to the end of their journey, and even though we don’t actually see their deaths we feel them just as strongly.

19. Werckmeister Harmonies

This Hungarian black and White movie is about the Soviet occupation of Hungary at the end of the Second World War. It also shows their journey among helpless citizens as a dark circus comes to town casting an eclipse over their lives.

It is composed of thirty nine languidly placed shots and the final one leaves viewers pondering over the symbolic and the deeper meaning behind what they have just witnessed, which suits the tone perfectly as the entire film has been described as a visual poem, both haunting and beautiful, rhythmic and hypnotic.

It finishes with the main character staring into the eye of a beached whale, then, walking away and looking back at the now sad and dishevelled creature, destroyed by rioters the night before, its rotting carcass slowly enveloped by the fog which gets whiter and brighter.

What does it mean? It could be an allegory for a once powerful nation that now lies helpless and at the mercy of another power. Or does it represent the savagery of man, or the inevitable obscurity that awaits us all? Regardless of what the whale represents, it is simply an evocatively beautiful image and leaves a lasting impression of bleakness and demise. It may not be a hopeful message but it sure is prolific.

18. Aguirre, the Wrath of God

Werner Herzog’s 1972 epic is a contemplative journey of insanity and obsession. The story follows the travels of Spanish soldier Lope de Aguirre, who leads a group of conquistadores down the Orinoco and Amazon River in South America in search of the legendary city of gold, El Dorado. Surrounded by nothing but the unforgiving rainforest, Aguirre’s men are slowly picked off one by one, falling victim to the harsh environment, distrust amongst their comrades or disease.

The remainder of the group are then attacked by natives and being too feverish, starved or bewildered to retaliate they simply die. All that remains is Aguirre himself on the slowly drifting vessel, and a hoard of monkeys that have invaded his raft. He becomes delusional himself and begins to make plans to conquer Spain, and then the world.

The final shot itself is an unbroken encirclement of his raft, emphasising his complete and utter isolation. It represents the fact that by this point Aguirre is not just separated from all other humans around him, he has left his own humanity behind, having been lost in a sea of greed, obsession and gluttony.

17. Dancer in the Dark

The word haunting may appear on this list quite a bit and sorry if you think it’s overused, but there is no better way to describe the final shot of Lars Von Trier’s tragic story of Selma Jezkova, an immigrant woman in Washington D.C in 1964 who finds escapism from her day to day life by imagining everyone around her as part of a huge musical number (you know, as you do). She tries to obtain money to save the eyesight of her son and becomes embroiled within a coup de grâce in the process.

Tragically, she is put on trial as a murderess and communist sympathiser and sentenced to death by hanging. If you have seen it you will know, it’s a tough watch and the film’s final image is so melancholic in its nature that it stay with you long after the credits have finished.

From the shock factor generated by the lifeless corpse suspended so delicately, from the way that Von Trier frames the body to the almost casual way in which the guards draw the curtains across, everything about the shot emphasises tragedy and heartbreak as well as the inhumanity behind the act. As the camera lowly pans across the gallows, it’s an image you are unlikely to forget.

16. Bad Lieutenant: Port of Call New Orleans

Another Werner Herzog movie makes the cut, but despite being another moment of quiet beauty, this time it represents something a bit more ambiguous. The film features what has to be one of Nick Cage’s best performances in which he plays a police officer who saves a man from drowning, but is injured in the process and becomes addicted to pain killers and narcotics, slowly drifting into a sea of corruption.

Having emerged through the ordeal, still heavily reliant on drugs and put in a position of higher power, the bad lieutenant finds himself at an aquarium, sitting next to the man whose life he saved at the start of the film. The man has been sober for almost a year and offers to help him finally escape his own addiction.

Cage’s response is a question relating to whether or not fish have dreams, and the two men simply sit with their backs against the tank. Not only is it subtly beautiful it’s a perfect closing shot for Cage’s story. Does this represent a baptismal rebirth or is he still trapped within the murky waters from which he started this journey? We don’t know, but it’s a morally ambiguous ending for a morally ambiguous movie.

15. Raging Bull

One of the most painful and pitiful stories of self-destruction in cinema history leaves us with an oddly haunting scene that speaks everything about Jake La Motta’s progression, what he was and what he has become?

In the simplest terms, even though he claims to be remorseful for his actions his inner rage still lies buried beneath him. His animalistic aggression is still the dominant factor of his actions and he cannot escape the life of a boxer. He still refers to himself as ‘champ’, shadowboxes to prepare for a stand-up routine and psyches himself up in a disturbingly aggressive fashion.

But of course, before that comes De Niro’s rendition of Marlon Brando’s famous monologue from On the Waterfront. Once again we are left wondering, what exactly does it mean? Is it La Motta’s recognition of his past mistakes, proving he is human enough to admit his flaws? Or is he once again wrecked with paranoia, blaming those closest to him for his problems and failing to see that he is the cause of his own downfall? The mirror to which he addresses this monologue to, is he condemning his own reflection and view of himself, or admiring it?

It is yet another ending that lends itself to interpretation. Regardless, the fact the shot also captures De Niro’s performance in all its glory is yet another bonus. Here is a man who drove everyone who loved him away with his suspicion, jealously and rage and yet this performance still somehow evokes empathy for the boxer. Even if we don’t forgive La Motta, we pity him.