As the quality of the films of the 50s continued through to the 60s, and the economical growth continued in an unwavering rhythm, Japanese cinema experienced its most prolific decade, with hundreds of movies produced from major and independent studios.

This second aspect was an outcome of the rise of the Japanese New Wave, which started in the 50s and continued into the 70s, but flourished in this decade. Young directors, most of whom were previously employed by major studios, left (or were fired), since they decided to abandon the dominating forms, themes, and opinions, as they devoted their works to questioning, analyzing, critiquing, and (at times) upsetting social conventions.

Nagisha Oshima, Seijun Suzuki, Hiroshi Teshigahara, and many more were “products” of this movement.

This new tendency would shape a large part of Japanese cinema in the following years, as the masters of the past, like Yasujiro Ozu and Mikio Naruse, shot their last films in this decade.

Here are 20 of the best films of the 60s, with a focus on diversity. I have made an effort to place the titles in order of quality, but due to the number of masterpieces included, the order could easily be different.

20. Night and Fog in Japan (Nagisa Oshima, 1960)

“Night and Fog” is probably the most difficult Nagisa Oshima film to watch, since, apart from the slow pace and the extensive dialogue, it requires knowledge of Japanese politics in order to understand the allegories its characters present.

The film starts at a 1960 wedding party and gradually it is revealed, through their speeches, that all the guests know each other from their political past. Using flashbacks, Oshima presents the past of each member, and then through heated dialogue, he presents their points of view regarding Zengakuren and the AMPO treaty.

The film retains a theatrical style, but as time passes, Oshima focuses on the discussion, leaving all film aspects to the side. The same applies to the technical department, since the movie is visually captivating in the beginning, but then just focuses on the dialogue. In that fashion, it becomes evident that the director, a former leftist activist himself, chiefly wanted to present his opinion regarding the two aforementioned subjects, and simply used film as his medium.

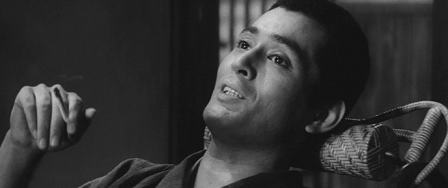

19. Go, Go, Second Time Virgin (Koji Wakamatsu, 1969)

This is probably one of Koji Wakamatsu’s simplest films, primarily due to its miniscule budget that forced the director to shoot it in four days, almost exclusively in a sole location: a rooftop.

Four boys carry Poppo, a teenage girl, against her will onto a rooftop, where they rape her. A fifth boy, Tsukio, witnesses the incident; however, he stands passively on the side watching it happen. Although the other boys leave, he remains through the night waiting for her to wake up. In the morning, the two of them begin discussing their lives.

Wakamatsu deals with themes of sex and death in adolescence, portraying the former as something awful and violent, and the latter as the only form of solace. Additionally, revenge, the omnipresent subject of the exploitation genre, is also present.

The film is nihilistic, a characteristic primarily emerging through the dialogue of the two protagonists. Technically, Wakamatsu uses his usual approach of shooting chiefly in black and white, splashing color when he wants to underline a scene.

18. Immortal Love (Keisuke Kinoshita, 1961)

Despite being one of the lesser-known films from Keisuke Kinoshita, “Immortal Love” was Japan’s entry for the Best Foreign Language Film at the 1961 Oscars, and is one of his greatest works.

This dramatic tale centers on a woman named Sadako, whose fiancé, Takashi, a tenant farmer, is fighting in China. When the landowner’s son, Heibei, returns wounded from the front, he informs her that Takashi has been injured and will probably die at the hospital in Shanghai where he is being treated. Heibei lusts after Sadako, and one night he rapes her and then convinces her father to let her marry him. The film then follows the story of their family for three decades.

Kinoshita directs a film based on a complex and quite abnormal relationship, since Sadako and Heibei stay together because they hate each other, in a never-ending effort to make each other miserable that even extends to their son.

The characters’ behavior is quite annoying, with Heibei being vile and Sadako being sarcastic and passive-aggressive. However, due to the wonderful direction, and the great performances by Tetsuya Nakadai and Hideko Takamine, the whole situation makes sense in an almost incoherent way.

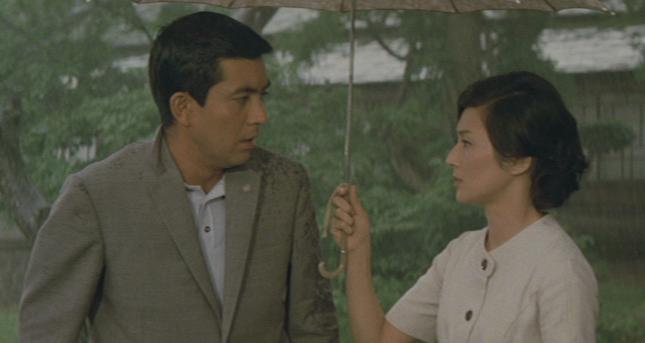

17. Scattered Clouds (Mikio Naruse, 1967)

Shiro accidentally kills another man in a car accident, and despite his innocence, his company sends him to a remote branch in a small city. Before he leaves, because he is tormented by guilt, he gives the victim’s widow a large sum of money. She decides then to move back to her hometown to recover. Naturally, the town is the same one where Shiro has been transferred, and a romance begins between them.

Mikio Naruse directs a film about a doomed relationship with his distinct patience, rhythm, and attention to realism. In that fashion, he presents the two protagonists connected with everyday life, and the other people of the town, instead of detached, in a world of their own, as is usually the rule in similar films.

His unpretentious style of shooting is present, with minimal camera movement, and each frame a masterpiece by itself.

16. An Autumn Afternoon (Yasujiro Ozu, 1962)

Considered one of his finest works, Yasujiro Ozu’s “An Autumn Afternoon” was also his swan song, as he died the following year.

Hirayama, a widower, is an ex-Navy officer who currently works as manager of a factory. He lives with his 24-year-old daughter, Michiko, and 21-year-old son, Kazuo. His older son, Koichi, is married to Akiko and has moved out.

During one of Hirayama’s regular reunions with classmates from middle school, the appearance of an old teacher shocks him. The teacher has fallen on hard times; he has become a drunkard, and is reliant on his bitter daughter, who missed the chance to marry when she was young and is now too old. Seeing the analogy between him and Michiko, he decides to marry her as soon as possible.

Ozu directs a very tender film, which is mostly based upon the tragicomical effort of Hirayama to marry his daughter, despite her protests. As both of them are willing to sacrifice their happiness for the sake each other, the film also takes a dramatic turn.

His regular themes of family, dependence, marriage, and the relationship between parents and children are once again present. What is impressive, though, is how personal the film is, with Ozu identifying with Hirayama, since he lived for 60 years with his mother, and when she died, he was dead a few months later.

15. The Insect Woman (Shohei Imamura, 1963)

Tome is a lower-class girl born out of wedlock in a rural farming village in 1918. The girl soon realizes that her mother is promiscuous, although her foster father loves her dearly. Perplexed by fate and men, she jumps from one relationship to another and eventually becomes the mistress of their neighbor, who employs her in his mill. She has a child with him, but soon abandons it to her father and leaves for Tokyo.

Starting to work as a prostitute, she finally becomes a success in Tokyo as a “madame” and the mistress of an executive. However, at one point, he seduces her illegitimate daughter.

Shohei Imamura directs an allegory about life in Japan in the 20th century, including World War II. Through Tome’s life, he presents the socioeconomic background of the country, as he watches her like an entomologist would watch an insect caught in the same eternal cycle.

Sachiko Hidari is great in the titular role, acting with simplicity and naturalness, in perfect harmony with the film’s permeating realism.